Diverse Voices: Chien-Shiung Wu, “The Chinese Marie Curie” | Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation

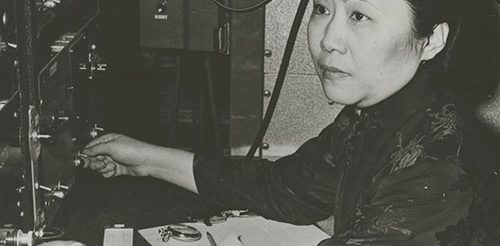

Physicist Chien-Shiung Wu (1912-1997). Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 90-105, Science Service Records, Image No. SIA2010-1509

Born May 31, 1912, just after the Chinese Revolution began, Chien-Shiung Wu [note: I will use Western format of Chinese names] grew up with two brothers in a small town near Shanghai. Their mother Fan-Hua Fan was a teacher, and their father Zhong-Yi Wu was an engineer who played an active role in the early years of the political rebellion. Unusual for the time, their father advocated for girls receiving an equal education to such an extent that he founded the Mingde Women’s Vocational Continuing School, which young Wu attended. She went on to study physics at National Central University in Nanjing, graduating at the top of her class in 1934. After graduation, she joined a lab led by another female physicist, Jing-Wei Gu, who encouraged Wu to continue her education in the United States.

With financial support from an uncle, Wu emigrated by ship across the Pacific Ocean, bound for graduate school in the San Francisco Bay Area. Between 1936 and 1940, she completed a PhD in nuclear fission at the University of California, Berkeley, where she worked with Nobel Prize-winning physicist Ernest Lawrence. At Berkeley, Wu also met and married Chinese-born physicist Luke Chia-Liu Yuan (who was a grandson of Shikai Yuan, the first albeit short-lived President of the Republic of China). Because World War II was raging when they wed in 1942, neither of them could share the happy news with their families back home.

Wu moved East with her family to take teaching positions first at Smith College, then Princeton University, and finally Columbia University, where she joined the infamous Manhattan Project in 1944. At that time, Manhattan Project researchers were working secretly towards the creation of an atomic bomb. Wu’s research as part of the instrumentation group included improving Geiger counters for the detection of radiation and the enrichment of uranium in large quantities. She also helped develop the process for separating uranium into uranium-235 and uranium-238 isotopes by gaseous diffusion. In addition, she was the first person to develop an experiment to confirm Enrico Fermi’s 1933 theory of beta decay, a type of radioactive decay in which a proton is transformed into a neutron (or vice versa) and unstable atoms become more stable as their ratio of protons to neutrons becomes equal. Wu’s resulting publication, Beta Decay (1965), is still a classic reference in nuclear physics.

Chien-Shiung Wu with chemist Wallace Brode (at Wu’s left) and a group of science talent search winners at Columbia University, 1958. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 90-105, Science Service Records, Image No. SIA2010-1510

Wu gave birth to their one son, Vincent Wei-Cheng Yuan, in 1947. He carries on the family physics legacy as a nuclear scientist at the Los Alamos National Lab. Her husband, Luke Chia-Liu Yuan, had his own successful career as an experimental physicist at RCA and Brookhaven National Lab.

In 1956, her Chinese-born colleagues Tsung-Dao Lee at Columbia University and Chen Ning Yang at Princeton University jointly proposed a theory that would disprove a then-widely accepted law of physics called the “Parity Law.” The law of parity stated that all objects and their mirror images behave the same way, but with the left hand and right hand reversed. Yang and Lee needed a way to prove their theory in practice, so they asked Wu to create an experiment to do so. Wu agreed and designed experiments at the National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology) in Washington, DC.

As described by the Manhattan Project National Historic Site: “To test the theory, she put cobalt-60 (a radioactive variety of cobalt) into a strong electromagnetic field at temperatures near absolute zero. The cold helped eliminate the effect of temperature on the atoms. If the conservation of parity held true, particles expelled by the cobalt-60 as it decayed from radioactive to stable should fly off in all directions. What she observed was that more particles flew off in one direction (the direction opposite to the spin of the nucleus). Therefore, conservation of parity did not happen during beta decay.”

An article in the New York Herald Tribune (January 16, 1957) excitedly announced that Wu’s achievement “opens the way to a whole new set of explanations of the atom, the world and the cosmos. Her work, you now see it integrated into what is called the Standard Model of particle physics.”

Chien-Shiung Wu won the American Association of University Women (AAUW) Achievement Award in 1959 for her important contributions to physics. From AAUW Journal, October 1959, courtesy of AAUW.org

Beyond the so-called “Wu Experiment,” which gained her fame in the physics field, her research also crossed over into biology and medicine, including the study of the molecular changes in red blood cells that cause sickle-cell disease.

Throughout her career, Wu achieved many “firsts.” She was the first woman president of the American Physical Society; the first woman hired to the physics faculty at Princeton and also the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from Princeton; and the first woman to receive the National Academy of Sciences’ Comstock Prize in Physics. She was also the first person, man or woman, to win the prestigious Wolf Prize in Physics in 1978. Wu was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1958 and received the National Medal of Science in 1975. In 1990, astronomers at the Ziijnshan Astronomical Observatory in Nanjing discovered an asteroid and named it in her honor—a first for a living scientist—called the “2752 Wu Chien-Shiung” [using the standard Chinese format of family name first].

Chien-Shiung Wu, with colleagues Y. K. Lee and L. W. Mo, who confirmed the theory of conservation of vector current in 1963. In the experiments, which took several months to complete, proton beams from Columbia University’s Van de Graaff accelerator were transmitted through pipes to strike a 2 mm boron target at the entrance to a spectrometer chamber. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 90-105, Science Service Records, Image No. SIA2010-1508

However, in what was widely considered a deplorable professional snub, Wu did not receive the Nobel Prize for her successful experiment that proved Yang and Lee’s theory. Her two younger male colleagues shared the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics for “their penetrating investigation of the so-called parity laws which has led to important discoveries regarding the elementary particles.” Many people, including Wu, believed she was overlooked simply because she was a woman. I found a telling quote from Wu in a Newsweek article, titled “The Queen of Physics” (May 20, 1963): “It is shameful that there are so few women in science [in the US]. In China, there are many, many women in physics. There is a misconception in America that women scientists are all dowdy spinsters. This is the fault of men.”

Postage stamp featuring nuclear physicist Chien-Shiung Wu, issued by the U.S. Postal Service in 2021. Courtesy of United States Postal Service

In 1954, Wu became a US citizen, and did not return to her homeland until 1973—37 years after she first arrived in America. Sadly, her uncle and a brother were killed during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and her parents’ tombs were destroyed. Wu passed away in New York City on February 16, 1997. Her ashes are buried with her husband’s in the courtyard of her father’s Mingde School in China. After her death, Wu received public recognition in this country when the National Women’s Hall of Fame inducted her in 1998 and the US Postal Service issued a stamp featuring her image, one of three issued in 2021 to honor the achievements and culture of Asian Americans.

Sources: