Glassblower makes innovation possible for Chevron chemists

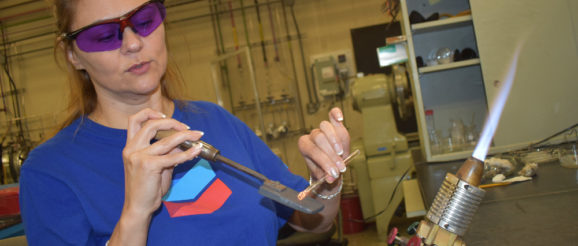

For Marianna Pittner, glassblowing isn’t art.

“It’s a science,” she says.

She means it in a literal sense. Pittner, who is among an increasing number of women working in traditionally male-dominated STEM fields, is also among a rare breed of scientific glassblowers who work in laboratory research.

For 20 years, Pittner has been the go-to glassblower at the Chevron Richmond Technology Center (RTC), where she is tasked with creating a wide variety of custom glass apparatus for a fleet of ambitious chemists. From a sizable workshop equipped with torches, lathes and oodles of glassware of varying heat sensitivities, Pittner repairs and creates beakers, test tubes and a host of other glasswear that Chevron scientists need in their quest to modernize the production of transportation fuels, lubricating base oils and other related products. The fuel additive Techron, for example, is one of the more widely known inventions created at the RTC.

On a daily basis, chemists drop into Pittner’s workshop with requests to create custom glass pieces of varying specifications. At times, she’ll create pieces straight from examples that chemists draw by hand in notebooks. Often, she’ll meet with chemists to come up with blueprints for designs that solve problems in the research process, such as creating glass apparatus that manipulate direction of flow and temperature of the solutions undergoing tests.

“I will never tell the chemist I can’t do that,” Pittner said. “I will figure it out; I enjoy the discovery. You have be very logical and problem-solving to make it in this field.”

Pittner didn’t expect to become a scientific glassblower. Originally from Hungary, she initially tried to get into a training program to create custom design jewelry from precious stones. She was told she couldn’t enter the school, but also informed about a training school on scientific glassblowing, which she found interesting.

She joined the full-time training school where she learned about the craft, its history, technical drawing, safety, chemistry, math and other subjects. She earned a Masters in glassblowing after three years, then took additional chemistry courses for two years to embolden her knowledge.

How rare are scientific glassblowers? When she applied for the position at Chevron, she said she was offered her job five minutes into the interview, in large part after she told them she’d completed her education in the Hungarian program.

Members in the American Scientific Glassblowers Society’s members have reduced from 1,000 members to about 500 in a half century, according to UC Berkeley, which recently profiled one of its on-campus glassblowers, Jim Breen. Only about 50 work at college or universities, said Breen.

The combined skillsets of craftsmanship, science and problem-solving skills isn’t easy to come by. As Pittner points out, the problems solved in her workshop aren’t the type you can Google for answers.

“Some things we work on don’t even have a name yet,” she says.

Chevron benefits from an in-house glassblower because it is more efficient in both cost and time, and a good way to protect patents from the competition, Pittner said.

“My chemist comes in and says, ‘Marianna, can you add this or that on this, and I say, sure, come tomorrow and pick it up,’” she said. “You have to be creative because sometime they don’t know what they want. They just know what they want to have happen. And then we just talk about it for a while and we try it and then go back. Maybe it worked, maybe it didn’t. I always say everything is possible.”

Having someone with that skill and confidence is highly valuable, said John Greene, Distillation Process Technical Team Leader who has been working with Pittner for 10 years.

“Glassblowers are not a dime a dozen,” Greene said, “but a well sought-after commodity. Marianna’s quality is unmatched. She creates a variety of instruments (her lab looks like it belongs to a mad scientist), and her glassware is necessary to collecting accurate data and creating superior distillation research.”

Pittner said there have been many candidate glassblowers who walked into her shop, saw the degree of technicality in her work, and either walked right out or didn’t last very long.

While she has the respect of her colleagues, however, Pittner says a woman in a male-dominated field still has to earn it in the way a male colleague doesn’t. When a researcher she doesn’t know walks in to greet her, they may ask to speak with the scientific glassblower on duty.

“It is hard to achieve instant respect, what men get right away,” she said. “If I was tall and burly and named Christopher, they would think differently. But when I create a product I can see chemists coming in with a little more respect, [as if to say] ‘Oh, she knows. Interesting.’”

And in addition to pleasing the chemists, Pittner can proudly state that, despite the scorching temperatures she deals with, she’s had no injuries in 20 years. She said she appreciates Chevron’s approach about safety, including the company-wide mantras: “Do it safely or not at all,” and, “There is always time to do it right.”

“It’s very important,” she said. “You don’t rush, because maybe it will cost more if you hurry.”

The challenge, and concentration, needed in the field is, perhaps, why Pittner doesn’t view glassblowing as art. After a long day in the workshop, she said she has no thoughts whatsoever about doing any glassblowing at home.

“I love this job because it’s creative,” she said. “I’m constantly designing things for Chevron, and it’s very fulfilling to know my glassware is helping chemists develop something new.”