Join the Innovation Revolution with NextFlex and Manufacturing USA! – EEJournal

I have to say that I’m flabbergasted. In fact, I don’t think it would be unfair to say that rarely has my flabber been quite so gasted. The reason for my current state of high-gast is that I just received some frabjous intelligence with respect to enhancing our manufacturing capabilities here in the USA.

One of the things that’s made me increasingly sad over the years is how much manufacturing and expertise we’ve frittered away (“lost to overseas competitors” is another way of thinking about it). Something else I think we’ve largely lost, and the loss of which I deeply regret, is the concept of apprenticeships by which folks can get paid to learn a trade. However, I’ve been told something that has brought a twinkle to my eye, a smile to my face, and a flush to my cheeks (and my face has gone red as well).

The reason for my current impish grin is that I was just chatting with Art Wall, who is Director of Fab Operations at NextFlex, which specializes in the creation of flexible hybrid electronics (FHEs) of the additive flavor (Ooh, tasty!).

As a wise man once said, “A gentleman is someone who knows how to play the bagpipes… but doesn’t.” On the other hand, just to make sure that we’re all tap-dancing to the same skirl of the Scottish bagpipes (as opposed to Irish bagpipes or English bagpipes), a crisp and concise definition of FHEs from the NextFlex website reads as follows:

Hybrid Electronics are driving the next generation of electronics by providing PCB manufacturers and heterogenous packaging experts novel solutions such as the advanced additive hybrid electronic systems we are creating. Flexible and additive hybrid electronics gives everyday products the power of silicon ICs by combining them with new and unique low-cost and environmentally friendly additive printing processes and new materials. The result is fast time to market, lightweight, low-cost, and highly efficient smart products that can be flexible, conformable, and stretchable with innumerable uses for consumer, commercial and military applications.

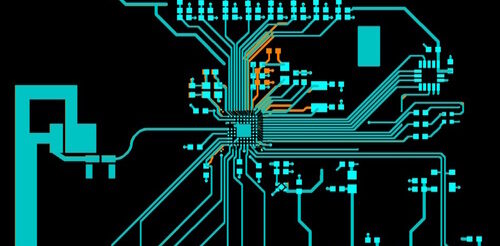

An example of this technology is the A21 flexible microcontroller as illustrated below (the processor itself is the teeny-tiny bare die provided by Nordic Semiconductor mounted in the middle of the flexible substrate).

The A21 flexible microcontroller (Source: NextFlex)

The A21 is the fourth generation of NextFlex processor technology. It started as a basic processor intended to provide a demonstration to capture the imagination. When people started to use it for real projects, the guys and gals at NextFlex began to add capabilities like Bluetooth. This latest generation is designed to allow them to quickly spin variants boasting the processor augmented with various sensor combinations as required by different users.

We will return to NextFlex in a moment, but first we have to consider the larger picture. It turns out that NextFlex is one of sixteen institutes that have been formed around the USA, each targeting different types of technology, but all with the same general focus, which is to take an emerging technology, create a consortium of like-minded organizations (industrial, academic, government), and mature the technology to the state where the United States can establish a meaningful manufacturing ecosystem in that area of expertise.

In addition to NextFlex and its FHEs, these institutes span a wide range of technological domains, including advanced composites, integrated photonics, functional fabrics, biofabrication, biopharmaceuticals, and… the list goes on. The umbrella organization over all these institutes—the mothership, if you will—is called Manufacturing USA.

Are you familiar with the terms technology readiness level (TRL) and manufacturing readiness level (MRL)? I wasn’t, but I am now. Originally developed by NASA in the 1970s, and subsequently adopted by such organizations as the European Space Agency (ESA) and the US Department of Defense, TRLs provide a method for estimating the maturity of technologies during the acquisition phase of a program. Meanwhile, MRLs are quantitative measures used to assess the maturity of a given technology, component or system from a manufacturing perspective. They are used to provide decision makers at all levels with a common understanding of the relative maturity and attendant risks associated with any manufacturing technologies, products, and processes being considered.

The way Art explained this to me is that an MRL of 1 means that nobody has even figured out how to make the first one yet. At the other end of the scale, we have an MRL of 10, which equates to being in a state of full-rate production with lean and mean production practices in place.

In the context of our discussions here, the term “Valley of Death (VoD)” is used to refer to the area in the middle between the very early stages of conceiving a new manufacturing technology or process and the fully-fledged commercialization of that technology or process.

As Art says, “The VoD is where we live. That’s the purpose of these institutes. Not to do the fundamental early research, but rather to take things through the MRL and TRL 4 to 7 range. This is oftentimes where federal and DARPA-like funds have dried up, but industry hasn’t picked the ball up and started running with it yet. So, that’s really at the core of what all these institutes are trying to do—to push their technologies through their VoDs and get them into manufacturing.”

The NextFlex institute was founded in 2015. One of the things asked of all the institutes is to do something with respect to education and workforce development. Art tells me the folks at NextFlex are extremely proud of how successful they’ve been in this area. So successful, in fact, that eight of the other institutes have licensed NextFlex’s learning program to take into their own ecosystems.

Do you remember my saying at the start of this column that I think we’ve largely lost (and I deeply regret this loss) the concept of apprenticeships by which one can get paid to learn a trade? Well, Art says they have a program called “Learn and Earn” that mimics an apprenticeship. This is not a European style apprenticeship per se, but it fulfills the promise inherent in its name by allowing people to spend time at one of the institutes or associated companies and actually get a paycheck while dipping their toes in the industrial waters.

When NextFlex, was formed, its founders made a conscious decision that they didn’t simply want to stand proud in the crowd on the podium conducting the orchestra—they also wanted to be found in the orchestra pit playing one of the instruments (I’m visualizing a trombone, because that’s what I used to play in my hometown’s school orchestra). Thus, they formed their own fab facility, thereby allowing them to participate in a big way with respect to developing and maturing FHE technologies. That’s what Art does. He’s the Director of Fab Operations or, as he puts it, “I’m the one who has all the fun toys” (you can take a virtual tour of Art’s fab if you wish.)

The great thing about the consortium concept is that everyone brings something different to the party. In the case of the consortium of which NextFlex is part, some members have expertise in the printing part of the process, while others shine when it comes to pick-and-place or attaching bare die to flexible substrates. Members of the consortium who need to learn something outside their own bailiwick can come to the folks at NextFlex, who will help to de-risk the members’ investments in whatever areas they wish to grow.

Obviously, there’s a charge for all this, but this charge pales into insignificance when compared to the mitigation of risk and the return on investment. I was tempted to say that NextFlex is a non-profit organization but, in fact, it’s essentially three different organizations under one roof. The principal organization is a 501c6 nonprofit. Since they’ve been so successful in education and workforce development, they formed a separate 501c3 nonprofit to be eligible to accept educational grants and things of that ilk, of which they’ve already enjoyed several successes. Last, but not least, they formed a for-profit C Corp, which is where engineering and the fab falls. This means they can do work for anybody, and any profit derived from the C Corp helps to offset the cost of running the consortium in the first place.

There’s so much more to all of this. For example, the folks at NextFlex started with single-sided flexible substrates and then moved to double-sided implementations in which the sides are linked with conducting vias (just like regular circuit boards). Now they are experimenting with multilayer substrates, which come in two flavors—one involves printing multiple layers of conducting and insulating inks, while the other involves bonding multiple double-sided substrates separated by insulating layers. Meanwhile, the silicon dice they are using are shaved so thin that they also become flexible. Another area of experimentation involves embedding the silicon dice in the flexible substrate (see also the NextFlex Flexible Hybrid Electronics Manufacturing Roadmap).

The whole ethos underlying the foundation of NextFlex fits in nicely with the more recent goals embodied by the CHIPS and Science Act, which are to lower costs, create jobs, strengthen supply chains, and mitigate potential problems should bad actors cause things to go pear-shaped on the technology front in other parts of the world.

All I can say is that I’m tremendously enthused to hear that those who don the undergarments of authority and stride the corridors of power are aware of the need for the USA to once again be at the forefront of manufacturing, especially when it comes to the latest and greatest 21st Century technologies. What say you? Do you have any thoughts you’d care to share on anything you’ve read here?