Made in New York? Innovation Economies and Immigrant Precarity

By Tarry Hum

New York Works

As one of New York City’s last remaining industrial waterfront neighborhoods, Brooklyn’s Sunset Park figures prominently in Mayor de Blasio’s 2017 New York Worksplan, which laid out priority industry sectors and strategies to create 100,000 middle class jobs that pay a minimum $50,000 annual salary within the next decade.[1] The targeted industry sectors and job creation projections are: 30,000 jobs in technology (especially in cybersecurity); 25,000 jobs related to new office districts (such as East Midtown) and outer borough commercial centers; 20,000 jobs in industry and manufacturing based on reactivating the city’s vast industrial infrastructure and implementing the Freight NYC plan; 15,000 jobs in life sciences and health care; and 10,000 jobs in creative and cultural sectors that define and promote New York City’s global brand. Overseeing the Mayor’s New York Works is the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYC EDC), a quasi-public “self-sustaining” non-profit organization charged with leveraging the city’s assets to catalyze and shape economic growth and job creation.[2] NYC EDC also owns or manages 66 million square feet of commercial real estate, making it the fourth largest landlord in New York City.[3] The job creation strategies outlined in New York Works emphasize land use actions and capital investments in infrastructure and commercial real estate. For example, EDC is investing several hundred million dollars to renovate massive city-owned industrial complexes such as the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Brooklyn Army Terminal. In addition to the Brooklyn Army Terminal, city-owned industrial campuses located on Sunset Park’s waterfront include the Bush Terminal, Brooklyn Wholesale Meat Market, and South Marine Brooklyn Terminal. Mayor de Blasio’s February 2017 press conference to announce plans for a Made in NY campus was met by a tenant’s earnest plea to “(P)lease keep small manufacturing at Bush Terminal.”

Bush Terminal February 2017, Photo by Glaucio Silva.

In March 2018, the New York City Council held a public hearing to address New York Works, But for Whom? Examining the New York Works Jobs Plan.[4] Led by Councilmembers Ritchie Torres and Paul Vallone, Chairs of the Oversight and Investigations, and Economic Development Committees respectively, much of the hearing centered on EDC President and CEO James Patchett’s testimony and responses to questions on the efficacy of New York Works. Councilmember Torres’s district includes Bronx neighborhoods with high poverty and unemployment rates, and his opening statement cited Charles Dickens to highlight contemporary parallels to skyscrapers that “block the sun” on deteriorating NYCHA buildings while the city spent $127 million to construct a municipal golf course, Trump Golf Links, and continues to pay the Trump Organization to operate the leisure facility.[5] According to Councilmember Torres, the purpose of the public hearing was to hold NYC EDC accountable for the Mayor’s “pretty words” about confronting income inequality and “lofty political goals” to create pathways to middle class employment and stability.

The hearing on New York Works focused on two areas of contention. One is NYC EDC’s methodology of tracking job creation, which Councilmember Torres described as “uncertain at best and woefully inaccurate.” During questioning about job projections versus actual job creation, NYC EDC’s James Patchett conceded that in the first year of New York Works implementation, $300 million dollars (of a $1.3 billion dollar commitment) was spent to create only 300 jobs.[6] The second issue pertains to equity and economic justice. The present challenge is not job creation per se; in 2018, the NYS Comptroller reported the city’s record high of 4.5 million jobs and a low 4% unemployment rate.[7] Rather, the challenge is one of equity and fairness — in other words, job creation for whom? Are the middle class jobs resulting from city investments and land use actions accessible to low-income New Yorkers who typically lack a high school diploma and English language proficiency? To underscore his concern, Council Member Torres pointed out that Connecting New Yorkers to Good Jobs is slated for only $27 million, a mere 2% of New York Works’ $1.3 billion commitment.[8] Questions of economic justice are especially pertinent to city investments and economic development initiatives in Sunset Park.

This essay examines how public and private actions to reactivate and reposition Sunset Park’s industrial spaces as a hub for innovation contributes to rising property values and a rent gap defined by the differential between market rents and rents paid by manufacturing tenants. Property owners are incentivized to sell or convert their industrial properties (and displace small manufacturers) in order to realize these potential rent revenues. As a heavily working class Latinx and Chinese immigrant neighborhood, NYC EDC’s commitment to grow an “inclusive” economy rings hollow in light of Mayor de Blasio and his administration’s disregard for the harsh conditions common in immigrant labor niches and the continuation of punitive policies that augment economic hardship for food delivery cyclists, taxi drivers, and street vendors.

Sunset Park Innovation District and Made in NY

Sunset Park’s waterfront is a designated Significant Maritime Industrial Area[9] and Industrial Business Zone (IBZ),[10] and is ground zero for post-industrial gentrification. Once the site of an industrial ecosystem, its infrastructure comprised of brick factory loft buildings, piers, and a railroad network are being reactivated by public and private investments for an innovation economy and the space needs of makers and designers in media, film, art, fashion, and technology. These creative sectors support and require lifestyle amenities especially food halls and festivals, bike lanes, and venues for dance parties and art exhibitions.[11]

Industry City is a privately owned behemoth comprised of a 16-building factory and warehouse complex connected by courtyards covering six city blocks. Its consortium of investor owners is led by Jamestown Properties, which specializes in “reinventing [industrial buildings] as innovation hubs.”[12] Jamestown Properties has proposed a rezoning to add 1.3 million square feet of destination retail, luxury hotels, and parking for at least 2,000 cars. Since acquiring its ownership share in 2013, Jamestown Properties has secured a massive Bank of China commercial mortgage to make deferred maintenance and re-brand the complex through the strategic placement of public relations pieces such as a 2017 article that described Sunset Park as “a little-known Brooklyn neighborhood” that “is having a moment.”[13] Possibly the most significant land use proposal in Brooklyn, Jamestown Properties’ Special Sunset Park Innovation District would irrevocably transform the waterfront from an industrial ecosystem to a work-play campus for an elite creative class.

There is synergy between private and public investments to remake Sunset Park’s waterfront into a “global model for inclusive innovation and economic growth.”[14] NYC EDC spends hundreds of millions of dollars in infrastructure including the expansion of broadband in the city’s IBZs and new transportation modes.[15] In 2017, the NYC Ferry added a Sunset Park stop, and while passengers pay the same fare as the subway, the cost of a ferry ride is subsidized at over $10 per passenger.[16] To improve Industry City’s streetscape, NYC EDC is spending $38 million in the repair and beautification of 37th to 43rd Streets between the Gowanus Expressway and the waterfront. NYC EDC is investing $136 million to transform Bush Terminal into a “state-of-the-art” Made in NY film and TV production studio.[17] To promote the relocation of garment manufacturers faced with displacement in Midtown Manhattan, Made in NY will also provide “small white-box spaces” for 25-35 garment tenants.[18] Further south, NYC EDC hired Cushman and Wakefield, a global, high-end real estate brokerage firm, to market space in the Brooklyn Army Terminal.[19]

Contested Terrain

Sunset Park’s extensive factory, warehouse, and piers infrastructure is testament to its integral role in the city’s historic manufacturing and port economy, and to the unionized, blue-collar jobs that helped lift thousands of New Yorkers and their families into the middle class.[20] Starting in the 1960s, many urban manufacturing centers outsourced first to the south and then overseas in search of ever cheaper sources of labor. Providing a necessary corrective to a market-dominated narrative of deindustrialization, the work of Robert Fitch[21] and Joel Schwartz[22] provide critical insight on New York’s governing elite and growth coalition’s deployment of land use actions and economic development practices to hasten and augment the demise of industrial employment and space in favor of rebuilding New York as a center for global finance and advanced services.

Once the largest garment production site in the United States, New York City continues to pride itself as the Fashion Capital of the World despite a much diminished local manufacturing base. In 1960, 95% of clothes sold in the United States was produced in thousands of small factories in numerous Manhattan neighborhoods.[23] The 1965 Hart-Cellar Act, which eliminated racist quotas and established family-based admissions categories, catalyzed a steady stream of Asian, Latinx, and Caribbean immigrants, many of whom revived and sustained the garment industry through the early 2000s as workers and factory owners. At its height in the 1980s, Manhattan Chinatown was a key production site with approximately 500 garment shops and a workforce of 25,000.[24] Today, Chinatown’s garment industry is virtually gone.

The September 11 tragedies dealt a fatal blow to Manhattan Chinatown’s garment industry, already weakened by global competition and free trade agreements.[25] Chinatown rebuilding led by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) and local leaders sought to redevelop the neighborhood as a gateway for Pacific Rim capital.[26] LMDC’s $7 million allocation for post-9/11 economic development was largely spent on street cleaning and supporting the formation of a controversial business improvement district, the Chinatown Partnership Local Development Corporation. Prominent garment factory owners such as John Lam also invested in and developed local properties and now, the Lam Group is a self-described transnational “real estate conglomerate.”[27]

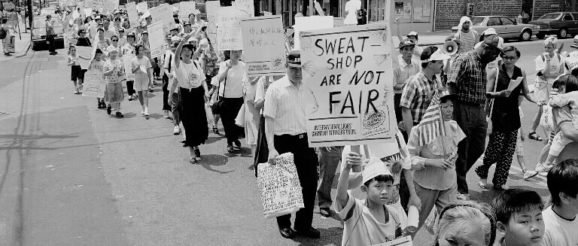

In search of cheap rents and the absence of union representation, Manhattan Chinatown garment contractors and manufacturers started to move to Sunset Park in the 1990s. Sunset Park’s garment industry is based on two distinct geographic clusters – factories in Bush Terminal and Industry City, and the mixed-use area adjacent to the 8th Avenue N subway station. In 1995, Congresswoman Nydia Velazquez, union leader Edgar Romney, and Assemblyman Felix Ortiz (all still in office) led a march on 8th Avenue to protest Sunset Park’s sweatshop conditions.

Sunset Park Garments Worker Rally June 2015, Photo by Mike Dabin, New York Daily News

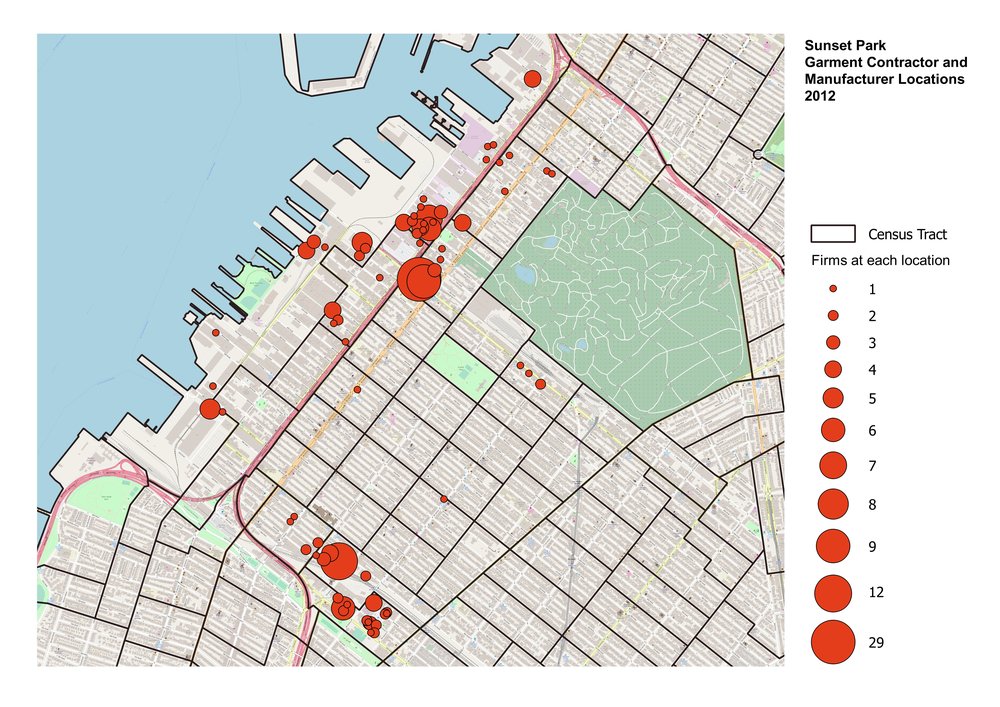

As late as 2012, Sunset Park retained a sizable garment manufacturing sector comprised of nearly 200 contractors located in the two dense geographic clusters, and Sunset Park was the largest garment production district outside the Midtown Garment Center.[28] Although these garment contractors were registered with the NYS Department of Labor’s Apparel Industry Task Force, meaning that the firms met basic labor standards, many of Sunset Park’s manufacturing spaces were located in converted garages or warehouses with no windows or a second means of egress, and in operation beyond regular business hours.

2012 Density Map of Sunset Park Garment Contractors and Manufacturers, Data Source is NYS Department of Labor Apparel Industry Task Force, Prepared by Manju Adikesavan.

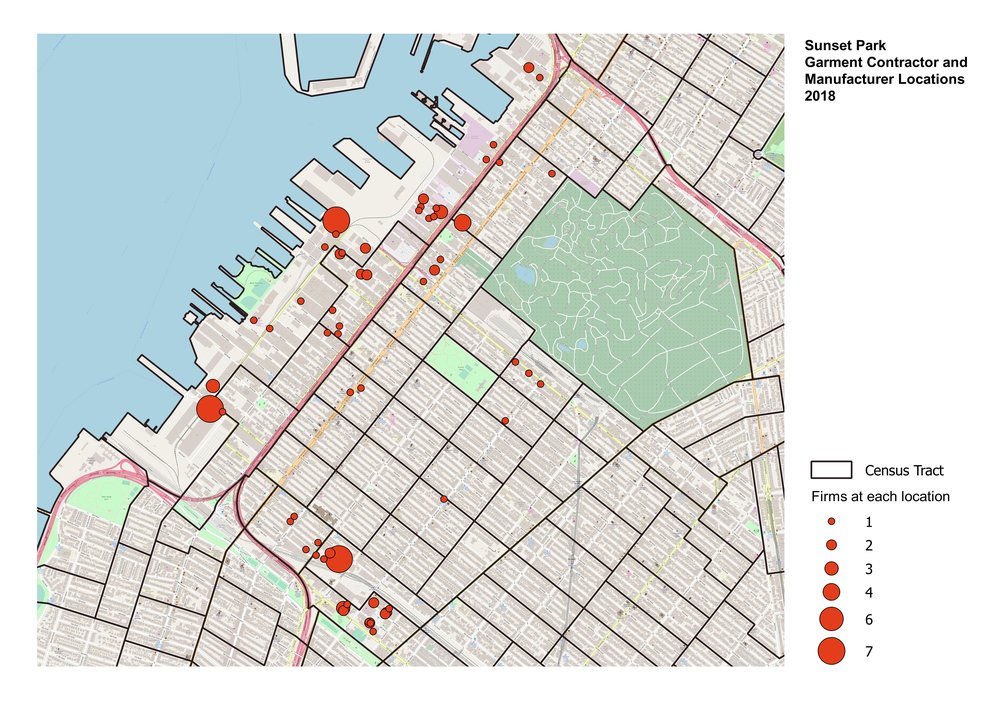

By 2018, the number of garment factories declined by nearly half with the greatest loss in Industry City and one huge factory building located directly across 39th street. In the five years since 2012, Industry City garment contractors were reduced by 71% from 42 to only 12 firms.[29] The adjacent 39th Street factory building was sold to a real estate investment company for $18.5 million in June 2013. Three years later, the building, emptied of more than thirty garment manufacturing tenants, was sold for $37.6 million, more than double the initial purchase price. The building has since been renovated into modern commercial office spaces while maintaining the industrial loft aesthetic. This property transaction and conversion exemplifies how Sunset Park’s industrial properties have become financial vehicles for optimizing real estate profits.

2018 Density Map of Sunset Park Garment Contractors and Manufacturers, Data Source is NYS Department of Labor Apparel Industry Task Force, Prepared by Manju Adikesavan

The displacement of industrial businesses that have long anchored Sunset Park’s neighborhood economy underscores the marginality of immigrant economic niches and the complicity of city-led economic development initiatives in fueling real estate speculation and the adaptive reuse of industrial spaces for more profitable commercial and retail use. Even in industrial properties such as Liberty View Industrial Plaza (formerly Federal Building #2) with a deed restriction to promote light manufacturing uses including garment production, landlords warehouse space in order to “curate” a tenant mix that pay premium market rents.[30]

Immigrant Precarity

While Industry City’s proposed Sunset Park Innovation District and EDC’s Made in NY campus stated mission is to support modern manufacturers or makers in design and fashion, Sunset Park’s long-neglected garment industry continues to exist as immigrants labor in visibly substandard conditions. Hidden in plain sight, city policy makers still fail to reckon with the persistence of informality in immigrant labor markets. The Senior Vice President of Sunset Park Asset Management explained that NYC EDC does not have “the boots on the ground” to check out the neighborhood’s “distinct” immigrant garment cluster. She emphasized that firms have to undergo an “extensive background check” in order to be a tenant and eligible for various business assistance programs. Given these significant “barriers to doing business with the city,” some tenants are simply “not interested” in locating in city-owned properties.[31] While planners and policy makers appear to know informality is integral to advanced urban economies, immigrant workplaces and communities are still treated as spaces of “marginality and irrelevance.”[32]

Typical Sunset Park Garment Factory August 2018, Photo by Tarry Hum

Current real estate trends and prospective mega-development projects including the MTA Request for Proposal for the 61st Street air rights project, which entails the construction of a platform from 8th Avenue to Fort Hamilton Parkway for new residential and commercial development, portend the imminent demise of surrounding garment factories. Immigrant workers rely increasingly on employment agencies that staff Chinese and Asian fusion restaurants throughout the Northeast region and beyond.[33] Through leveraging city-owned properties and investments in infrastructure, tax abatements and subsidies, EDC claims to seek a “double bottom line strategy targeting not just economic returns but also multiple social metrics” such as job creation and equitable neighborhoods. Since the city owns nearly 6 million square feet of industrial space in Sunset Park, the neighborhood is a testing ground for the issues of equity and economic justice that were raised at the March 2018 New York City Council hearing on New York Works. Recently, a coalition of neighbors and activists complained about immigrant exclusion in community discussions and review on the impending Industry City rezoning.[34] Based on current real estate investments and development trends, post-industrial placemaking through a Sunset Park Innovation District and Made in NY campus will surely deepen immigrant precarity and further marginalize the neighborhood’s majority working poor.

To be clear, my study of Sunset Park’s garment manufacturing sector is not based on nostalgia or a desire to bring back the “factory job just like my grandparents did”[35] which in my case, would be my mother’s job as she labored in a garment sweatshop for decades.Rather, I focus on garment manufacturing to acknowledge and honor the invisible labor of immigrants and people of color that have always served as the backbone of New York City’s global economy and brand.Despite immeasurable contributions, immigrant production exists largely in peripheral spaces until these spaces become valuable to owners and investors.If the city is serious about growing an inclusive innovation economy, all its investments and public actions especially rezonings would be driven by the imperative to address the existential crisis of our time – climate change.UPROSE’s Green Resilient Industrial District is a plan that would protect one of the city’s last working waterfronts and meaningfully engage in innovative thinking and strategizing for climate adaptation, green manufacturing, and a circular economy.Rather than pursue the age-old imperatives of what CUNY geographer Samuel Stein terms the “real estate state,” Sunset Park presents an opportunity to become a global model for truly innovative and inclusive solutions to the crises of immigrant precarity, racial inequality, and climate change.

Tarry Hum is Professor and Chair of Queens College’s Department of Urban Studies. She also serves on the Doctoral Faculty at the Graduate Center’s Environmental Psychology program. She is the author of Making a Global Immigrant Neighborhood: Brooklyn’s Sunset Park (Temple University Press, 2015).

[1] 4,000 jobs by the end of de Blasio’s second and final term in 2021.

[2] According to a 2019 NYC Council Report on NYC EDC’s Fiscal 2020 Executive Budget, NYC EDC is unique and unlike other City agencies, and concerns regarding public accountability and financial transparency are long-standing.

[3] Lauren Elkies Schram “Power Landlords: The Guys Who’ve Got the Biggest Portfolios in New York,” Commercial Observer, April 23, 2019.

[4] A video of the March 18, 2019 hearing is available from the NYC Council Committee on Oversight and Investigations website.

[5] Winnie Hu and Emily Palmer. “Trump Golf Course Struggles in Bronx, Where Many Can’t Afford to Play.” The New York Times, June 2, 2017.

[6] Jorgensen, Jillian. 2019. “De Blasio’s jobs plan has spent $300 million but has only created 3,000 jobs so far.” New York Daily News, March 18.

[7] Office of the New York State Comptroller, “New York City Employment Trends,” Report 10-2018, February, https://www.osc.state.ny.us/osdc/rpt10-2018.pdf

[8] Connecting New Yorkers to Good Jobs refers to workforce development and training, industry partnerships, and CUNY curriculum development to meet industry-specific employer needs, and GED support. For more information, see https://newyorkworks.cityofnewyork.us/industries/connecting-new-yorkers-to-good-jobs/

[9] Significant Maritime Industrial Areas are defined by clusters of industrial firms and water-dependent businesses.

[10] Industrial Business Zones are designated areas with a high concentration of industrial businesses and will not be rezoned for residential use.

[11] Erica Berger “Gentrification, Inc.” FastCompany, August 7, 2014.

[12] “Jamestown Lures Reebok By Innovating Through Tenant Curation,” by Cameron Sperance, Bisnow Boston, February 24, 2017.

[13] Sarah Jacobs, “A Little-Known Brooklyn Neighborhood Was Named One of the World’s Coolest Places–Here’s What It’s Like,” Business Insider, October 16, 2017.

[14] The New York City Economic Development Corporation’s mission statement, https://www.nycedc.com/about-nycedc/mission-statement

[15] Former Deputy Mayor Alicia Glenn quoted in https://technical.ly/brooklyn/2015/01/13/sunset-park-fiber-broadband-alicia-glen/.

[16] Citizens Budget Committee March 2018 report, “Swimming in Subsidies: The High Cost of the NYC Ferry” https://cbcny.org/research/swimming-subsidies

[17] Julianne McShane, “Lights, camera, action! City bringing TV and film production to S’Park,” Brooklyn Paper, August 20, 2018.

[18] Devin Gannon, “As it creates new fashion hub in Midtown, the city still pegs Sunset Park as next garment district,” 6sqft, October 4, 2018.

[19] Rebecca Baird-Remba, “EDC Hires Cushman to Market Space in Brooklyn Army Terminal,” Commercial Observer, July 31, 2019.

[20] For more on the centrality of unionized manufacturing jobs in postwar New York, see Joshua Freeman, Working Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War II (New York: The New Press, 2000).

[21] Robert Fitch, The Assassination of New York. (New York: Verso, 1993).

[22] Joel Schwartz,The New York Approach: Robert Moses, Urban Liberals, and Redevelopment of the Inner City. (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1993).

[23] Samanta Cortes, “Manhattan’s Garment District still a vital part of NYC labor market, cultural history — and here’s how we can save it.” New York Daily News, April 22, 2017.

[24] Xiaolan Bao, “Sweatshops in Sunset Park: A Variation of the Late 20th Century Garment Shops in New York City,” International Labor and Working-Class History, Spring 2002, pp. 69-90.

[25] Kenneth J. Guest and Margaret M. Chin,“Chinatown, the Garment and Restaurant Industries, and Labor” in City of Workers, City of Struggle; How Labor Movements Changed New York, edited by Joshua Freeman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019).

[26] “Revitalizing Chinatown Businesses: Challenges & Opportunities, A Report From The Asian American Federation.” May 2008.

[27] “Mining Chinatown’s ‘Mountain Of Gold,’” by N. R. Kleinfield, New York Times, June 1, 1986 and see Lam website bio – https://lamgroupnyc.com/about/

[28] NYC’s Garment Industry: A New Look? Fiscal Policy Institute 2003, pg. 8

[29] Based on my analysis of NYS Department of Labor Apparel Industry Task Force block and lot level data for 2012 and 2018.

[30] Tarry Hum, “Get Ready Sunset Park, ‘Brooklyn’ Is Coming:” The Real Estate Imperatives Of An Innovation Ecosystem,” Progressive City, July 11, 2017.

[31] Phone interview with Julie Stein, NYC EDC Senior Vice President, March 5, 2019.

[32] Vinit Mukhija and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris,“Reading the Informal City: Why and How to Deepen Planners’ Understanding of Informality,” Journal of Planning Education and Research, 2015.

[33] Zai Liang, Jiejin Li, Glenn Deane, Zhen Li, and Bo Zhou,“From Chinatown to Every Town: New Patterns of Employment for Low-Skilled Chinese Immigrants in the United States,” Social Forces, 2018, 1-27.

[34] Anna Quinn, “Chinese Are Afterthought In Industry City Rezone, Immigrants Say.” Patch, August 15, 2019.

[35] Industry City CEO quoted in Anna Quinn, “Industry City Rezone In Their Own Words: A Sit-Down With The CEO.” Patch, August 28, 2019.