Part II: Can Uganda and Kenya become Africa’s hub for crop biotechnology innovation? – Genetic Literacy Project

Erostus Nsubuga, who sits on the Presidential Roundtable for Investments in Agriculture, and serves on several well-placed boards of state-enterprises in commerce and farming, juxtaposed the current Kenya-Uganda GM-crop technology scenario to the one in Latin America in 1990s. That’s when Brazilian farmers adopted GM-soya and corn from their Argentine counterparts even as their (Brazilian) Government hadn’t approved it. Soon after, the Brazilian government followed suit, and it is now one of the largest producers of GM crops in the world.

We who are in favor of GM-technology shouldn’t worry because it seems Government wants Uganda to remain a mere recipient of improved technologies; so we shall get GM-seeds from Kenya, soon and very soon. In fac,. Bt-cotton seeds could be the first to come into farmers’ hands.

Based on the latest data, Uganda produces only 200,000 cotton bales annually [2019/20 period], down from 300,000 in 2018/19. The lepidopteran bollworms is one of the biggest pest threats. There is a genetically modified version which naturally repels the worms that’s available. Other threats include weeds, the high cost of husbandry and pesticides, all of which could be reduced with GM seeds, also have reduced yields.

Estimates put the crop yield increase from using GMO-technology at between 6-25 percent depending on the country. It would be particularly helpful in Uganda, which has two rainy seasons each year and possesses 40% arable land.

Prospero Lonyo Ocheng, a Ugandan nutrition scientist and immediate past National Coordinator at UBBC, noted that for over 15 years, biotechnology research has been funded by the government and a number of philanthropic institutions. Products developed by Ugandan scientists have promising results, and this includes the blight-resistant potato, cassava mosaic/CBS-disease resistant cassava, water-efficient rice and maize among others. Now it’s time to leverage that, she said:

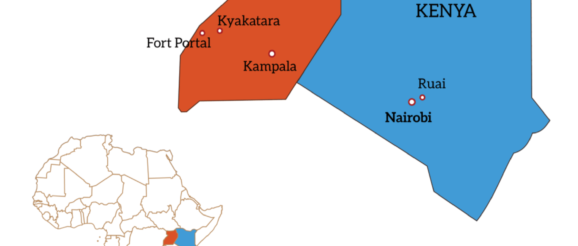

Now that the Kenyans are free to grow GMOs, our farmers along the border with Kenya will definitely look across and appreciate the benefits of the technology as their counterparts in Kenya will be reaping bountifully from their new-found seeds.

I can almost predict, she added:

… by the end of one season in Kenya, the whole of eastern Uganda will be ‘flooded’ with [Bt-cotton] seeds from Kenya since we don’t have any law stopping them from acquiring them…. To me, this is one of the best options for us to take as a country in need.

What happens if Uganda does not follow suit?

Ocheng, a bio-economy enthusiast, warned that Uganda stands to lose economically if it sits on the fence too Iong. “We shall soon become a museum for old agricultural technologies like the hand-hoe, yet new technologies have the potential to increase productivity by over four times what we are producing now….”

As of today, Uganda’s top agricultural exports to Kenya are maize, fruits especially bananas, passions, pineapples, legumes; eggs, milk, sugar, cassava and even chicken. Although those crops are grown in Kenya too, they are more expensive than Ugandan ones [due to their lower cost of production in Uganda], and which is more ecologically-endowed than Kenya. But that equation could change if Kenya begins embracing GM seeds while Uganda dithers.

Not following suit in Uganda and continuing to block GM crops could be economically catastrophic, Ocheng and others believe. If Kenya, Uganda’s biggest trade market, adopts GM-maize (insect resistant and pesticide tolerant) and insect-resistant GM-cassava (to CBSD), Uganda will have little to sell across its border.

In addition, local Ugandan seed producers will lose market as the farmers are likely to prefer to buy the modified seeds from Kenya. These seed companies need to be protected and given the opportunity to trade in the same or else they close shop. They say when Kenya adopts better technologies in agriculture — a field in which Uganda now has a competitive cost advantage—then its smaller, landlocked western neighbor [Uganda] is likely to be crippled unless they reach some settled/negotiated understanding over quotas like China and the United States, among other trading examples.

“For us when Kenya coughs, we catch a cold,” said Nsubuga, whose company supplies banana planting materials to Kenya among other countries in the EAC region.

It’s politics

Mzee Etellu has challenged President Museveni to pick a leaf from his Kenyan counterpart and permit GM-crops in Uganda. “These leaders are very close politically, can we as farmers in need of better agricultural technology benefit from their choices, Etellu said.

Advances in conventional breeding has not been able to keep up with the disease challenges facing Ugandan farmers. An excellent cassava variety developed by NARO-Uganda 5 years ago, ‘NAROCAS-1’ is already succumbing to rotting caused by the Cassava Brown Streak Virus (CBSV).

It is an extremely excellent variety, with a range of attributes from bread-food with sorghum/millet, roasted and boiled tubers derived in homes, by farmers, youth and women-traders. But it is not resistant to the CBSV as its root-tubers [which is the food] rot hardly after one and a half years in the soil. It gives us 10-15 tons per acre, compared to 2 tons per acre from old varieties that have long disappeared under disease and pest-pressure.

GM-technology counters this deadly CBSV, Etellu noted, adding that old varieties like ebwanatereka and ‘nigeria’ have been wiped out by CMVD and CBSVD in most of the Teso sub-region where he lives/farms. NARO scientists already have developed CBSV-resistant cassava — they just need to be greenlighted. Farmers would like GM-cassava varieties that last 3-5 years intact underground —unscathed by pests and diseases — as farmers pick off tubers for meals, or to dry and mill into ordinary flour for cassava-millet/sorghum bread or for High-Quality Cassava Flour (HQCF).

Our cassava farmers and [I], would adopt GM-varieties if we can access it. It is us who know best where the stone-in-the-shoe pinches our toes.” Today several companies in Uganda brew beers and spirits [gin] from cassava, besides bakeries/confectioneries and beverages using HQCF as a supplement to wheat, hence the label for cassava as an ‘industrial crop’. It is so valuable worth protection at any cost.

Lifting the ban in Kenya is likely to reduce demand for Ugandan maize, cotton, cassava, potato, soybean and banana among other Kenya crop-produce. Kenya plans to import over 10 million bags of GM-white maize for ugali (a popular maize bread in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda).

“The imports will be a competitive advantage of huge maize presence in Kenya but from a foreign GM-crop technology.… Kenya will definitely reduce the demand of maize more from Uganda. Our farmers are going to lose a big market,” said Dr. Andrew Kiggundu, a highly-experienced Ugandan ag-genetic engineer.

There’ll be unregulated introduction of GM seed into Uganda, he says, noting that the majority of eastern Uganda has been cultivating hybrid maize for more than 50 years, which first came in from Kenya, until Uganda also built capacity to develop her own hybrid-maize in 1990s.

“Increasing incidents of drought and demand for maize seed on the Ugandan side will definitely lead to illegal import into Uganda, similar to the case of GM eggplant (Bt-brinjal) smuggled from Bangladesh to India because of its benefits,” he forecast.

Kiggundu — who has worked in NARO and at the US-based ag research facility, Donald Danforth Plant Science Center (DDPSC) in St. Louis, Missouri — lists economic loss in form of employment and industrial opportunities if Uganda does not follow in Kenya’s path.

As Kenya which has been dependent on Ugandan cotton, shifts to the cultivation of superior GM Bt insect-resistant cotton varieties, could be most devastating to the country’s research and science projects: It will facilitate a brain-drain from Uganda, as the country’s best geneticists and agricultural scientists leave for employment in the Kenyan biotechnology industry.

Peter Wamboga-Mugirya is the Director of Communication and Partnerships at the Science Foundation for Livelihoods and Development (Scifode) and Executive Member of the Uganda Science Journalists’ Association (USJA).