Solid-state laser refrigeration can cool semiconductor material by at least 20 degrees C, or 36 F, below room temperature – Innovation Toronto

“Historically, the laser heating of nanoscale devices was a major problem that was swept under the rug,” said senior author Peter Pauzauskie, a UW professor of materials science and engineering and a senior scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. “We are using infrared light to cool the resonator, which reduces interference or ‘noise’ in the system. This method of solid-state refrigeration could significantly improve the sensitivity of optomechanical resonators, broaden their applications in consumer electronics, lasers and scientific instruments, and pave the way for new applications, such as photonic circuits.”

The team is the first to demonstrate “solid-state laser refrigeration of nanoscale sensors,” added Pauzauskie, who is also a faculty member at the UW Molecular Engineering & Sciences Institute and the UW Institute for Nano-engineered Systems.

The results have wide potential applications due to both the improved performance of the resonator and the method used to cool it. The vibrations of semiconductor resonators have made them useful as mechanical sensors to detect acceleration, mass, temperature and other properties in a variety of electronics — such as accelerometers to detect the direction a smartphone is facing. Reduced interference could improve performance of these sensors. In addition, using a laser to cool the resonator is a much more targeted approach to improve sensor performance compared to trying to cool an entire sensor.

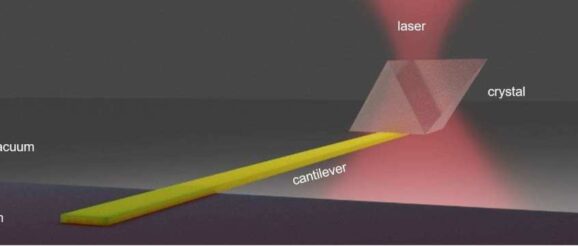

In their experimental setup, a tiny ribbon, or nanoribbon, of cadmium sulfide extended from a block of silicon — and would naturally undergo thermal oscillation at room temperature.

At the end of this diving board, the team placed a tiny ceramic crystal containing a specific type of impurity, ytterbium ions. When the team focused an infrared laser beam at the crystal, the impurities absorbed a small amount of energy from the crystal, causing it to glow in light that is shorter in wavelength than the laser color that excited it. This “blueshift glow” effect cooled the ceramic crystal and the semiconductor nanoribbon it was attached to.

“These crystals were carefully synthesized with a specific concentration of ytterbium to maximize the cooling efficiency,” said co-author Xiaojing Xia, a UW doctoral student in molecular engineering.

The researchers used two methods to measure how much the laser cooled the semiconductor. First, they observed changes to the oscillation frequency of the nanoribbon.

“The nanoribbon becomes more stiff and brittle after cooling — more resistant to bending and compression. As a result, it oscillates at a higher frequency, which verified that the laser had cooled the resonator,” said Pauzauskie.

The team also observed that the light emitted by the crystal shifted on average to longer wavelengths as they increased laser power, which also indicated cooling.

Using these two methods, the researchers calculated that the resonator’s temperature had dropped by as much as 20 degrees C below room temperature. The refrigeration effect took less than 1 millisecond and lasted as long as the excitation laser was on.

“In the coming years, I will eagerly look to see our laser cooling technology adapted by scientists from various fields to enhance the performance of quantum sensors,” said lead author Anupum Pant, a UW doctoral student in materials science and engineering.

Researchers say the method has other potential applications. It could form the heart of highly precise scientific instruments, using changes in oscillations of the resonator to accurately measure an object’s mass, such as a single virus particle. Lasers that cool solid components could also be used to develop cooling systems that keep key components in electronic systems from overheating.