The Art of Noticing: How Entrepreneurs Can Crack the Innovation Code

For many folks, coming up with an idea for a great business—or just any sort of idea for that matter—is a mystery. But for Rob Walker, the author of the new book The Art of Noticing, the key to creativity starts with making simple observations. The founder of the office supply chain, Staples, for instance, launched a multibillion dollar business after noticing he couldn’t buy a typewriter ribbon—remember those?—on a Sunday. The founders of Uber and Lyft hit the jackpot on ride sharing because we couldn’t find a cab when we needed one. They noticed that. The following is advice from Walker’s book. Maybe it will help you crack the code. Or at least help you find a little peace in your frantic day-to-day.

You likely don’t need to be convinced that we live in an era of maximum distraction, besieged by messages and updates, beleaguered by the sense that if we’re not up on the latest trending topic, we’ll be left behind. Even when we manage to pay attention to something unique or unusual or idiosyncratic, the mere fact that nobody else is chattering about it can make it feel unimportant.

That’s a mistake. Noticing things that everyone takes for granted—and that could be improved, amplified, repurposed or replaced—is often the first step toward innovation.

Sometimes it’s the most everyday observations that pay off. The Swiss engineer George de Mestral, for example, once got interested in how certain burrs stuck to his clothing on a nature walk. That’s not exactly bursting with hashtag potential, but it led to the invention of the hook-and-loop attachment system we now know as Velcro.

Progress requires attention. And that means giving yourself permission to tune out everybody’s takes on the news of the moment and attend to inspiration hiding in plain sight.

up

for our Newsletter

The connection between mindfulness and the determined focus that success requires—a businessworld trope for years—has never been more popular. And research has shown how curiosity benefits decision-making and creativity.

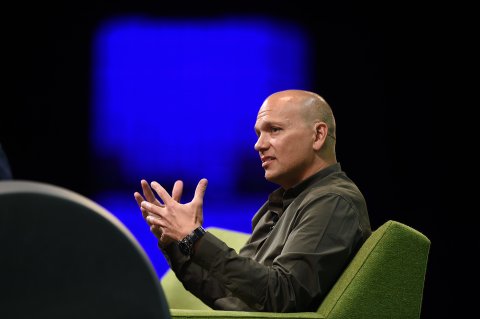

Yet, surveys also suggest that most workers feel that their curiosity is not encouraged. Managers should encourage creative attention and curiosity—but meanwhile, we don’t need anybody’s attention to notice what we notice. The designer Tony Fadell has talked about how maintaining an original, outsider’s eye guided his work on the iPod and later the Nest thermostat. “It’s seeing the invisible problem, not just the obvious problem, that’s important,” he has said, and this skill isn’t necessarily something you’re born with: “I had to work at it.”

So how do we do that? One strategy is to challenge yourself to see the world in new ways every day, forming habits that build your attention muscles. Think of them as prompts, provocations or even games. Here are three examples.

Replace Is With Could Be

The psychologist and Wharton School professor Adam Grant once described the benefits of “thinking in conditionals instead of absolutes.” He pointed to an experiment that tested whether subjects, divided into two groups, could figure out alternative uses for objects—for instance, deducing that a rubber band could be used to erase an error made in pencil. One group was given a narrow, specific description of: “This is a rubber band.” The other group heard descriptions that were more open-ended: “This could be a rubber band.”

The latter group, Mr. Grant explained, was thus primed to think conditionally—not to see what is, but what could be. In the group of conditional thinkers, about 40 percent realized that a rubber band can also be used as an eraser; in the group that received narrow descriptions, only three percent had the same epiphany.

Designers are often quite good at this kind of thinking, and in fact, this experiment made me think of an acquaintance of mine who calls himself Rotten Apple. He’s a designer whose work includes small-scale but highly creative “interventions” that transform overlooked urban flotsam into useful or appealing elements of the pedestrian environment. For instance, a clip-on seat could turn a bike stand into an impromptu chair, and discarded cutting boards could be converted into chess tables and installed atop fire hydrants.

On a more practical level, the entire smartphone app ecosystem is built on millions of answers to what a phone could be. We now take it for granted that the device can play the role of a map, a book, a radio, an alarm clock, a tape recorder, a camera, etc. One memorable example, app maker Smule’s Ocarina, linked an iPhone’s mic and touch screen to turn it into a flute-like instrument.

That’s impressive conditional thinking. But you don’t have to be a designer to exploit this strategy: Simply looking for an answer can shift and broaden your vision.

Change Your Route

The art of noticing what others miss is partly about building the habit of paying attention. But it can also be about breaking habits. Think about your commute: You go the most efficient way every day, right? And that makes sense. But it’s also why you’re on autopilot during that time, totally habituated to the routine.

Sometimes it’s worth it to make an effort to go out of your way, advises Jim Coudal, whose design firm Coudal Partners, based in Chicago, is best known for its role in creating the popular Field Notes notebooks. Every so often, try taking a different and totally inefficient route to work. “New routes make for more active and curious journeys,” he says.

The principle also applies more broadly: If you already know how to solve a problem with a tried-and-true method, see if you can solve it in a new way: “You never know what you’ll find along an unfamiliar route.” Give yourself the opportunity to see the world as an outsider would.

Think of Mary Anderson, an Alabama native who, on a 1903 visit to New York, was struck by the difficulty a trolley conductor had keeping the vehicle’s windows frost-free on a wintery day. The locals had become used to this problem and didn’t even think about it; Anderson hadn’t, which is why she was able to dream up and patent the windshield wiper.

Find Something to Complain About

Complaining gets a bad rap. But if nobody ever complained, nothing would ever improve. The trick is to treat negativity as a means, not an end. James Murphy, the founder of the band LCD Soundsystem, told interviewer Terry Gross that he realized that instead of lamenting the failures of other bands, he should focus on making the music he wanted to hear.

In a similar spirit, the author and marketing guru Seth Godin suggests a positively negative way to go about looking at the world: ask “What’s broken?” In other words, what, among everything you encounter, could be made better? The answer could be showers, pants fasteners, checkout lines, the cab area at the airport, the concession stand at a movie theater and on and on. “All around us is this huge potential—hidden potential—to make things unbroken,” he says.

Ride share services like Uber and Lyft, for instance, have been accepted by consumers because a lot of people saw taxi services as profoundly broken. The most important thing is to focus on your judgment, not the crowd’s. (After all, lots of people didn’t realize that the cab system was broken until they saw a clear alternative.) It’s precisely the thing you identify as broken—large or small—that gives you an opportunity to make a difference.

So look for the worst thing, the most broken thing, the thing that’s so bad it makes you mad. And let that inspire you to unbreak it.

→ Adapted from The ART OF NOTICING by Rob Walker. Copyright © 2019 by Rob Walker. Just published by Knopf. Cannot be reproduced without written permission of the publisher.