Cleantech innovation is being stifled. Here’s how to unlock it | World Economic Forum

In most of its applications, energy is a regulated commodity in a sector that provides low growth rates and in which competition is hampered by monopolistic market structures. Energy infrastructures are usually in place, but most are capital-intensive and fully developed, thus favoring the prevailing technology over innovative newcomers. If customers do not consider factors such as their carbon footprint or regionality in their purchase decisions, cost is the primary differentiation between competing energy products. In such an environment, innovative entrepreneurs face very difficult circumstances in their quest to establish new products and services.

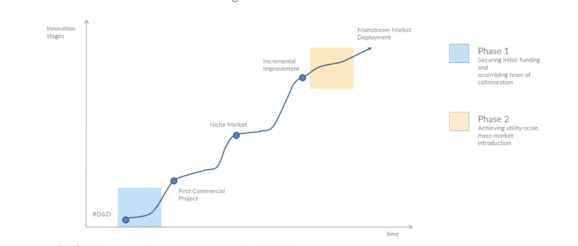

When taking a closer look at this environment for innovators, we can identify characteristic innovation stages according to which cleantech develops. Based on our work in this field, we consider two phases particularly critical: the first is a very early stage, in which bold ideas must obtain the necessary backing to secure initial funding in order to become a noteworthy research and development collaboration. Here, government and state-level support have to be won and entrepreneurs have to find and assemble the right team of participants for effective developmental collaboration.

The other major challenge is the phase prior to mass-market commercialization. This late-stage challenge centers around convincing utility-scale or institutional investor partners to join the project and carry it into a ‘first-of-its-kind’ mass-market application. The new cleantech hardware or software has to prove it can stand on its own feet with a sustainable business model (see chart above).

It goes without saying that many ventures and ideas deserve to fail because they do not bring with them an innovative effect that is fundamental enough – that carries a significant added value in terms of technology or process. If an endeavor would not result in a self-supporting, profitable business in the mid-term, any funding would be a waste of resources that would be more effectively allocated with other projects. The problem is that too many bright (and profitable) concepts have failed due to structural barriers at these innovation stages.

Established financing procedures usually meet expectations on a specific risk-return ratio. Venture capital (VC) funds, for example, invest in a basket of entrepreneurs, expecting the majority to fail but counting on exceptional success of some of their investments. Their expectations with cleantech investments during the industry’s ‘boom period’ between 2006 and 2011 have been particularly discouraging. The willingness of Sand Hill Road – the street running through Menlo Park and Palo Alto on which many major Silicon Valley VC companies have their offices – to take chances on sustainable technologies has dropped considerably ever since.

Cleantech innovators have so strongly disappointed the expectations of the VC scene, in fact, that funding has dried up considerably. In particular, hardware development in cleantech requires investors to hold their breath for longer due to its capital-intensive upfront investments and exceptionally long development cycles. Institutional investors (such as pension funds, insurances or sovereign wealth funds) control an enormous amount of financial resources. However, they still have a limited impact in cleantech development even though more and more of these funds have announced a focus on sustainable investment.

The number of public-private strategic investment funds is increasing, which allows institutional investors to contribute through minority or majority positions. Given the changing market environment, moving institutional investors towards earlier-stage deals and more high-impact technologies is a chance to revive the cleantech capital scene.

There are several innovative components of an innovation ecosystem to which policymakers can refer. Recent ideas include procurement-based reverse auction mechanisms (in which sellers bid for the prices at which they are willing to sell their goods or services), which would support market-based prices for not-fully-commercialized emerging technologies, or public reinsurance programmes, which would mitigate the early-stage technology risks faced by investors.

Policymakers have an opportunity to build cleantech ecosystems with a ‘magnetic effect’ of attracting both sustainable start-ups and bright minds to their region. If they manage to provide formal business development and investment support to regional cleantech startups, they can contribute to creating innovation ecosystems that reinforce their economic strength with sustainable business ideas. Regions which are undergoing structural changes in the energy transition – such as the lignite-rich regions in western Germany, with their current carbon-intensive generation portfolios – are particularly suited to host future cleantech clusters.

Taking all this into account, we have drawn four conclusions around how to increase the success rate of cleantech development and to secure the capital required for collaborative development efforts to make it to the commercialization phase:

Experts in laboratories and research institutions are not necessarily driven by an entrepreneurial spirit. Even though their ideas might be the next big thing in cleantech development, many researchers and engineers focus on the technical details of their technologies much more than they do on commercialization and securing funding for the upcoming innovation stages. So it is essential to closely monitor ideas which come from laboratories and support innovators in bringing together the right partners for development collaboration.

It is essential to pave the way for institutional investors. New approaches in blended finance should lower the bar for new investors with patient capital so they can significantly increase their commitment to funding cleantech. Both substantial funding and the will to invest in sustainable projects exist; the key challenge for innovative funds and policymakers is to unlock this potential. As new types of financing structures come into being, the procedural approach is actually secondary. Cleantech startups need patient capital with a longer time horizon and mission-based investment strategies. Approaches like the Sustainable Energy Innovations Fund by the World Economic Forum, Breakthrough Energy Ventures or innovative corporate finance consider these requirements in their set-up.

Financial support for cleantech entrepreneurs should be complemented by business development support. This includes guidance from people experienced in commercialization throughout all innovation stages to turn ideas from laboratory to scale. Energy innovators-turned-entrepreneurs face often unfamiliar demands: market and competitive landscape analysis, value proposition, product definition and prototyping. New funding mechanisms should therefore include mandatory mentoring components to increase the probability of bridging the critical innovation stages.