Inventing and Reinventing Stadiums | Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation

“A stadium is more akin to a machine than to a classical building or structure.”

– Bob Lang, architect

Stadiums and arenas have been on a significant growth trajectory since the late nineteenth century, with construction peaks aligning to forty-year cycles. Whether built for international competitions such as the Olympics and the FIFA World Cup, or for teams competing in national or regional leagues, significant resources are invested into stadium design, construction, and on-site entertainment technologies. New stadiums are not without controversy as critics decry the use (or misuse) of public finances, disruption to communities, and long-term environmental impacts. But over the past 120 years, a series of inventions has kept fans coming to stadiums, even as television and other technologies improved the home viewing experience. I suggest here that innovations in materials and construction, design of the spectator experience, and integration with nearby communities characterize three major periods of stadium building since 1900.

Global stadium construction by decade, adapted by the author from Wikipedia, “Category: Sports Venues Completed in the 20th Century”

With some notable exceptions, new stadium construction was geographically concentrated in Europe and North and South America from the late nineteenth century through the end of the twentieth century. Since the early 2000s, however, major projects in Asia and the Middle East have introduced innovations in stadium design and the spectator experience to new audiences.

The global spread of a novel coronavirus starting in early 2020 brought competitive sports to an abrupt stop. Stadiums currently sit empty while leagues are working through challenging scenarios for operating safely. It will be interesting to track how stadium design and the fan experience change in coming years.

1900-1940: Rise of the Modern Stadium

The city-states of ancient Greece and the Roman empire were avid builders of stadiums for sports and other competitions. Yet, when Pierre de Coubertin sought to revive the Olympic Games in the 1890s, he found no general “athletic stadium” available in Europe. Thanks to the Olympic movement and to the growth of European soccer and American baseball, the first wave of new stadium construction began at the turn of the twentieth century.

Initially, many of these stadiums were little more than fields surrounded by wooden grandstands, with minimal offerings beyond benches for seating and open standing areas. A design and construction breakthrough came with the 1908 White City Stadium in London. The stadium featured a visible steel frame, seating for 68,000 facing concentric circles of a cycling track and an athletics track, and a field sports and a swimming and diving pool located in the center. The White City Stadium was built in just ten months at one-third of the cost of stone or brick stadiums built at the time.

White City Stadium, London, 24 July 1908, from British Olympic Association, Fourth Olympiad 1908 London Official Report (London, 1909). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yet White City’s open steel frame design was not universally adopted. Instead, early college football stadiums in the United States were designed to invoke the Roman Colosseum. Meanwhile, fascist, communist, and other totalitarian governments in the 1920s and 1930s built large stone stadiums to encourage mass gatherings and to make charismatic leaders visible to the public.

1940-1980: Multipurpose and Enclosed Stadiums

After World War II, stadiums increasingly encircled spectators, who now identified primarily with teams representing their cities or regions. Innovations in constructing concrete multipurpose stadiums led to fully enclosed domed stadiums that could operate year-round and in less temperate climates. Function dominated over form, and stadiums were designed with convenient access to highways—and to discipline fans’ behavior by putting people into seats in physically separated stadium sections.

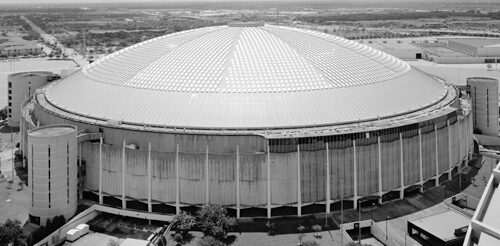

When it opened in 1965, the Houston Astrodome ushered in an era of enclosed and roofed stadiums, with an air conditioning system that cooled the entire building and a playing field made of synthetic Astroturf (natural grass had failed to grow). Marketed as the “eighth wonder of the world,” the Astrodome was part of a generation of multipurpose stadiums built to host both American football and baseball (the first was Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium in Washington, DC), along with music concerts and other large events. With seating for 42,217 when it opened, the Astrodome was surrounded by parking for 30,000 cars. It offered six levels of multicolored seats and was one of the first stadiums built with luxury suites and cushioned seating.

Houston Astrodome, with Astrohall rodeo and livestock exhibition building in foreground, around 1970. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration

Air-inflated stadiums enjoyed brief popularity in the 1970s, starting with the Pontiac Silverdome in Michigan, which was followed by approximately fifteen large arenas and stadiums using air pressure technology to hold up the roof. The Silverdome and other air-inflated stadiums suffered high-profile failures from weather, leading to their eventual abandonment.

For all of their innovations in convenience, the multipurpose stadium era proved unpopular with spectators. Although a “parking lot culture” grew up around some teams, stadiums were disconnected from their communities and the concrete bowl design proved boring for any but the most dedicated of fans.

1980-2020: New Urbanism, Environment, and Experience

By the early 1980s, stadiums were at a crossroads. Since television advertising drove revenue, in theory sports could be played without fans in smaller buildings designed for optimal camera angles. Concrete bowl stadiums had fallen out of favor with fans who felt distanced from the action. Soccer faced analogous challenges when stadiums were redesigned in the wake of deaths and injuries from crowd panics and stampedes.

When it opened in 1992, Oriole Park at Camden Yards set a new standard for American baseball stadiums through its incorporation of historical elements, integration with the surroundings, and contribution to the urban renewal of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor area. Putting the playing field below street level allowed for human-scale exterior landscaping, while its location alongside a historic warehouse at a rail terminus helped Camden Yards feel part of its surroundings. Popular with fans, similar retro stadiums were built around the United States in the next three decades.

Environmental issues also drove stadium innovations in the 2000s. Notably, the 2008 Beijing National Stadium—nicknamed “the Birds Nest”—included a geothermal system drawing on 312 wells to heat the stadium in winter and cool it in summer months. It also has a system to collect, filter, and use rainwater. Kaohsiung Stadium in Taiwan (opened in 2009) was the first stadium that generates all of its operating power from solar cells. Its roof is covered with 8,844 solar panels that generate 1.14 gigawatt hours of electricity annually.

The State of Qatar is aiming to integrate environmental and community innovations in the construction of seven new stadiums for the 2022 FIFA World Cup. The new stadiums were designed from the outset for rescoping after the world cup; are either connected to existing communities or have explicit near-term plans for sport, retail, and residential or other commercial communities; and each meets multifactor environmental standards, namely the Global Sustainability Assessment System (GSAS). The recently completed Education City Stadium, pictured at the top of this story, earned a perfect 5-star rating when measured for its energy consumption, water use, indoor environment, site impact, use of recycled and locally sourced materials, urban connectivity, and community association.

At the same time, stadiums have become crucial locations for the “experience economy.” New technologies developed since 2000 aim to soften and individualize the mass stadium experience through greater connectivity to handheld devices, on-site games, and other digital interactives for fans, along with other experiential features. Perhaps most notable in this category, SoFi Stadium in Los Angeles, the cornerstone of a $5.1 billion sports and entertainment complex, will feature a massive 70,000 square foot , double-sided “Oculus” display as well as a variety of opportunities for fans to select and even create and share media from their cell phones.

Game-Changing Stadiums

A child’s first view of a bright green stadium field (or pitch) and the roar of a crowd at a crucial score create memories that differ from watching television or even taking part in immersive virtual reality. Rather than signal the end of the stadium, the post-pandemic era will likely feature even greater community integration and design of flexible spaces to support a more individualized and mobile experience.

Curious to learn more or to discuss the future of stadiums? On 24 June 2020 at 12:30pm ET, the Lemelson Center is joining with SportTechie for a live discussion that will include the world premiere of 12 Game-Changing Stadiums in History, a new short-form video. A panel of historians, architects, and sports business professionals will discuss what makes a game-changing stadium and explore the future of stadium design and construction, especially for a post COVID-19 world. Visit https://thewayback.sporttechie.com for more information and (free) registration.