Marginal gains & continuous improvements: A holistic view of innovation

Innovation is often portrayed as some secret-sauce technology, protected by patents and company know-how. This post, however, looks at innovation through a different lens. It’s not about technology per se but rather the strategy that enables the technology to succeed. The process is known as marginal gains and continuous improvements, and it is used widely both in sport and business.

No human is limited

Achieving the impossible

On 12 October 2019, a quiet and humble Kenyan did what many believed was impossible – break the two-hour marathon barrier. His name was Eliud Kipchoge, and with a time of 1:59:40, he became the fastest marathoner in history. Those who are wondering, that is sub 2:50 min/km pace for 42.2 km (or around 4:34.5 per mile for each of the 26.1 miles). But one of the fascinating stories of this tale is the science that helped him achieve this superhuman feat.

Sponsored by Nike, Eliud and his team set about ‘Breaking2‘ by obsessing over every detail, no matter how small. They refined diet and hydration strategies, selected the fastest course to host the event, the perfect time of the year conducive to running, and even the formation of ‘pacers’ to reduce wind drag. And of course, there were the shoes, Nike’s ZoomX Vaporfly Next%, which have changed the course of history for better or worse and even brought about a rule change to the Tokyo 2021 Olympics.1

Marginal gains

We can see similar examples further afield. In 2002 when Sir Dave Brailsford became head of British Cycling, he introduced the strategy of marginal gains. The core principle was that if the team broke down everything they could think of that goes into competing on a bike, and then improved each element by 1%, they would achieve a significant aggregated increase in performance.2 The process worked – At the 2008 Beijing Olympics, his squad won seven out of 10 gold medals available in track cycling, and they matched the achievement at the London Olympics four years later. Brailsford describes some on the marginal gains:

By experimenting in a wind tunnel, we searched for small improvements to aerodynamics. By analysing the mechanic’s area in the team truck, we discovered that dust was accumulating on the floor, undermining bike maintenance. So we painted the floor white, in order to spot any impurities. We hired a surgeon to teach our athletes about proper hand-washing so as to avoid illnesses during competition (we also decided not to shake any hands during the Olympics). We were precise about food preparation. We brought our own mattresses and pillows so our athletes could sleep in the same posture every night. We searched for small improvements everywhere and found countless opportunities. Taken together, we felt they gave us a competitive advantage.

Continuous improvements

This philosophy is known as ‘Kaizen’, and it is a Japanese concept which emerged post-WWII referring to business activities that continuously improve all functions and involve all employees from the CEO to the assembly line workers. Both examples highlight how much better we can be when we take a holistic view of innovation.

“We need to be looking across the entire business model to find all of the 1% gains.”

Beyond the core focus

The philosophy of marginal gains and continuous improvements and its application to the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry, is something which has fascinated me for a long time. The AEC industry talks a lot about data-driven design – the process of using data to inform the design process. While I fully support this, it strikes me that this on its own is not enough to transform the industry. We need to be looking across the entire business model to find all of the 1% gains. And so just like what we saw in sport, that means looking beyond our core focus.

Finding the 1% gains

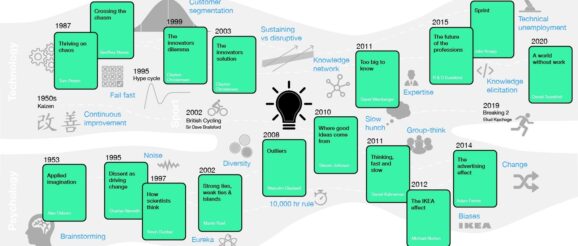

Eighteen months ago, I took an in-depth analysis to truly understand innovation – its definition, its origin, how to foster and cultivate it, and how to avoid failure. The research touched on economics, psychology, technology and even the future of the professions. And the results were fascinating.

I began by mapping the interconnected themes to understand better how our current understanding of innovation has been formed. Through Geoffrey Moore and Clayton Christensen, I discovered the difference between sustaining and disruptive innovation and why they require different strategic approaches. Through the extensive research of psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman, I discovered the pitfalls of group brainstorming – a practice used by almost every organisation to ill effect – and the cognitive biases that lead to poor decision making. I explored workshop techniques to foster structured decision making and prevent the endless decision wheel spinning. And research into well-documented advertising techniques highlighted how to influence behavioural change.

What became crystal clear from this research is that there were many aspects of innovation. Technology, on its own, wasn’t enough to succeed. Moreover, through my own experiences working in architectural offices, it became apparent that there was significant room for improvement across the industry in how we approach innovation.

Reflecting on our processes, much of our research had already filtered down into how we do things – From running structured decision-making workshops to our software workshops designed to maximise knowledge retention. But there was one aspect which stood out the most and required attention, our website.

Reflection & implementation

In many ways, Parametric Monkey is the website. When launched back in 2014, it’s aim was to accelerate computational literacy within the AEC industry. I realised that to transform the industry, we couldn’t restrict knowledge behind a paywall. We needed to reach as many people as possible and elevate the discourse. As John F. Kennedy famously said, “A rising tide lifts all boats.”

At the time, setting up a WordPress website was completely foreign to me. I didn’t even know the difference between a post and a page! And why would I? I had never had to develop a website before. But through my research, I discovered many flaws with the initial site design.4 If our intention was to educate, how we said things was just as important as what we said. And so it needed to be addressed.

Usability

For starters, the site didn’t even have search functionality. Since web users are either browse dominant or search dominate, that limitation reduced usability for many visitors. And with almost 80 tutorials, even browsing was a challenge. Luckily this issue was a simple fix, with users now able to search, filter and find related posts.

Transparency

It was also clear from particular commentary, that viewers sometimes didn’t read the entire article. While it seems impossible to eliminate over-zealous commentary derailing constructive discussion, we can reduce its likelihood. Like Medium, our posts now tell the reader approximately how many minutes it will take them to read the article. This simple inclusion has been shown to improve engagement.5 The more we know about something — including precisely how much time it will consume — the greater the chance we will commit to it. Any by committing to something, you have a better chance of achieving it.

You don’t know what you don’t know

In dealing with potential clients, it became apparent that it is often hard to imagine different ways of doing something if you’ve always done something a certain way. After all, you don’t know what you don’t know! We realised that we needed to showcase what was possible if we wanted to challenge our clients to do better things. So that’s what we did. We began by creating a showreel of how we’ve helped clients do better things.

Do better things

Updating our website is just one of the 1%’s we identified. There are, of course, many others that deserve attention. We’re not perfect but we hope that through these marginal gains, we can achieve significant improvement in our mission to help businesses do better things.

It can be tempting to focus solely on our core focus – be that architecture, engineering or construction. After all, it’s our core focus! But at some point, those wins are not going to be enough. If you want to truly do better things, begin by taking a holistic approach to innovation by questioning all facets of the process. Harness the mountains of scientific research and become more intentional about why and how you do certain things. In the words of Eliud Kipchoge, “no human is limited.” So together, let’s find our 1% gains and achieve the impossible.

2 Harrell, E. (30 Oct 2015). How 1% performance improvements led to Olympic gold. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston.

3 Harrell, E. (30 Oct 2015). How 1% performance improvements led to Olympic gold. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston.

4 Most of the flaws where as a result of reading Krug, S. (2014). Don’t make me think, revisited: A common sense approach to web usability, New Rider, Berkeley.

5 Holland, A. (14 Apr 2014). How estimated reading times increase engagement with content. Marketing Land.