How to fix what the innovation economy broke about America

Valerie Moreno laughed out loud when I asked if her family received regular medical checkups. “Oh my gosh, no!” she said. “We have to be dying before we see a doctor.”

The reason why wasn’t a mystery. Valerie, who was dressed in a sweatshirt and jeans, her dark hair showing a few grays, pulled her checkbook out of a small bag and riffled through the ledger. “I have $65 in the checking account,” she said.

Valerie and I first spoke early in the winter of 2018 as we sat in the basement of the First Lutheran Church in the small town of Bryan, in northwestern Ohio’s Williams County. The church’s pews had once been filled with worshippers. But people had drifted away, either because they’d stopped going to church or because they’d shifted their allegiance to one of the newer, fancier evangelical outfits. The room, sealed tight against the coming winter, marinated in a cloud of mustiness.

near a small village east of Bryan and has lived in the area her entire life.

Later that evening, Valerie would start her third-shift factory job at Sauder, a manufacturer of institutional furniture. She made $14 an hour there. When the sun rose the next morning, she’d drive to her second job, as a Bryan school bus monitor. Then she’d go home for a few hours of sleep before rising to work her third job, as a home aide to the retired pastor of First Lutheran. She reckoned she managed about four hours of sleep a day. Her husband worked full time at a metal fastener plant. Altogether, she said, after health insurance premiums but before taxes, she figured she and her husband made about $45,000 a year. They still had a junior-high-school-age daughter at home. They were living, but it was far from easy.

Valerie was 46. She’d worked all her life.

The story of her working life is also the story of Bryan. The town is broken in some of the same ways that much of the rest of the country is broken. Understanding what broke Bryan is crucial to understanding how it might be fixed.

For decades, America’s political and business leaders acted as if places like Bryan didn’t matter. Palo Alto and Greenwich, Connecticut, did fine. These centers of high tech and financial services create vast wealth in the country’s so-called innovation economy. But hundreds of places like Bryan, both urban and rural, were allowed to erode economically and socially. The innovation economy has largely passed them by.

Not everything is gloomy in Bryan, of course. If you were to drive through town, you would see some nice old homes, and parks, and a town square with a beautiful county courthouse. You might not notice the empty storefronts or realize that increased levels of poverty, mental stress, and poor health have led to desperation behind closed doors.

Some people think that when a town hits hard times, it’s time to pack up and move on to shinier places. Tim Bartik, a labor economist with the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in Kalamazoo, Michigan, disagrees. “Encouraging people to move does not help those left behind,” he says. “People have left Flint, but it didn’t help Flint. Flint is still there.” Instead, Bartik and others argue for a new regionalism, hoping to restore the vibrancy of places like Flint and Bryan through locally focused investment and education initiatives.

Developing a cogent regional development policy is one of the most vital public policy challenges facing America. President Joe Biden campaigned in part on the promise of creating “technology hubs” in 50 forgotten cities. But the diverging fates of places like Bryan and places like Palo Alto is clearly driving a loss of political faith. “It’s scary for democracy,” says Shannon Monnat, a rural demographer and sociologist who is the director of Syracuse University’s Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion. It “means deterioration of democracy and all the institutions that undergird democracy,” she says. “And I am worried it is getting worse.”

The slow-motion wreck

For decades after World War II ended, Bryan was a prosperous town of manufacturers, surrounded by farms and tiny villages that spread over the rest of Williams County. Its intracounty rival, Montpelier, was a minor railroad hub—the Montpelier school sports teams are still the Locomotives—with some manufacturing of its own.

During the middle years of the 20th century, small metal-stamping and injection-molded plastics makers set up shop to supply parts to the auto industry; Detroit is a two-hour drive away. ARO Equipment was Bryan’s biggest employer by far. Founded during the depths of the Great Depression, ARO first made air-powered pumps for things like gas station grease guns. By the late 1970s it had diversified. NASA used its pumps in space. Corporate jets flew out of the county airport; executives spent the weekend playing golf at the local country club.

Things were different by the time Valerie started her working life in the 1990s. Lots of changes hit Bryan hard: Reagan-era financial deregulation and anti-unionism, the creed of shareholder value as the highest goal of business, and the globalization of supply chains. The hardest blow came in the merger-mad 1980s, when ARO was bought by a failing company called Todd Shipyards. Todd wanted to acquire ARO’s pension fund to stave off bankruptcy.

Todd failed anyway, and in 1989 ARO wound up in the hands of Ingersoll Rand, a large maker of industrial compressors, power tools, and lifting gear. Ingersoll shut down the Bryan factory and moved the work to North Carolina, where union protections were weaker, and to plants in India and China.

Three early Bryan companies still operate: Spangler Candy, the Dum Dum lollipops people; Bard, a maker of heating and cooling equipment; and Ohio Art, the company that put the Etch A Sketch in the hands of millions of children in the 1960s. Each one is over a century old. But they are all diminished. Bard grew, but instead of expanding in Bryan, where it remains headquartered, it built new factories in Georgia, another state with weak labor laws, and in Mexico. Spangler also grew but now manufactures many of its candy canes in Mexico (though it also expanded operations in Bryan after acquiring the Necco Wafer, Sweethearts, and Bit-O-Honey brands). Ohio Art sold off its toys, sharply cut its staff, and focused on metal lithography.

Valerie worked at Bryan Metal Systems, making suspensions for Chrysler. She made good money there, but that company was taken over in 2005 by Global Automotive Systems. In 2010, Global shut down the Bryan plant and sent the work to Michigan as part of a “global optimization strategy.” Valerie traveled to Michigan to help train her replacements. After that, she bounced around, sometimes working temp factory jobs, until she landed at the Sauder furniture plant.

By 2019, unemployment was below 4% in Williams County, but higher-paying jobs had been replaced by work with low wages and “temporary” status that employers maintained—in name only—so they wouldn’t have to pay benefits. Menards, a big Midwestern home-improvement retailer, became the largest employer in the county. Menards wrangled a rich package of tax incentives and infrastructure out of local and state government in return for putting a distribution center about 15 minutes northeast of Bryan. By late 2019 people were starting at about $14 an hour, or about $28,000 per year, for full-time work. In the last 20 years, the median household income in Williams County (in constant dollars) has gone from $62,000 to $49,500. Defined-benefits pensions have given way to less-generous retirement savings accounts. Health insurance premiums have gone up. So have deductibles.

As the employment landscape changed, so did the county’s demographics. Young people, especially college-educated young people, left and didn’t come back. I asked Les McCaslin, the retiring chief of the Four County Board of Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Services and a native of the area, how he thought they might be persuaded to return. He remembered a recent economic development meeting: “We were talking about the town. And I simply said, ‘Why would you come here? Why would I bring my two kids?’ And there was silence in the room. You had commissioners there and they couldn’t come up with one reason.”

The Menards effect

Bryan’s hospital, Community Hospitals and Wellness Centers (CHWC), caught the fallout from these changes. As was true in many such communities, CHWC, an independent community hospital, became the largest employer in town. But it struggled to stay open and independent. Because the county’s population was getting poorer and older, many patients qualified for either Medicaid or Medicare, both of which pay lower reimbursement rates than private insurance. (The two government programs account for two-thirds of CHWC’s revenue.) So although, say, an MRI machine costs CHWC just as much as it would another hospital in a richer area, CHWC gets paid at a lower rate when it is used.

Former hospital CEO Phil Ennen calls this “the Menards effect.” The company was “a real problem for us,” he says. “Seventy-five percent of Menards [employee] accounts with us are Medicaid, charity, or some sort of self-pay. From a health-care perspective, they are a horrible employer.”

Many people were like Valerie: they just didn’t go to doctors. The spring after we sat in the basement of the church, Valerie was back there, this time counting Girl Scout cookie money with her daughter and a friend. She still worked three jobs. Her back ached from an old injury during her days at Bryan Metal Systems. And she was coughing from a bug she thought she’d caught from a coworker at Sauder. Valerie wound up with bronchitis, an inner ear infection, and a sinus infection, but she didn’t miss any work, because she had no paid sick leave. “No! I went to work every day,” she said, laughing, which called forth a brief coughing fit.

“The prospect of paying for a colonoscopy is a huge expense,” Mike Liu, a surgeon who practiced in Bryan, told me. “A single medical problem or medical bill could destroy their entire month’s budget—maybe their entire year’s budget.” This meant that treatable cancers went undetected until they were advanced.

But it isn’t just that people didn’t have enough money while medical care cost too much. Economic decline and poverty induce stress and trauma that in turn lead to poor health. The new American economy has been killing people.

From 1960 to 1980 life expectancy in the United States steadily increased. There were many reasons for this: vaccines against childhood diseases, improved community infrastructure, better antibiotics, and more advanced treatments for diseases like cancer. It was no coincidence that during this period, economic inequality in America decreased.

That started to change in 1981, when Ronald Reagan became president. He ushered in an era of union busting, financial deregulation, leveraged buyouts, and the financialization of the American economy. For a while, life expectancy continued to grow, but ever more slowly—until finally, in 2014, it began to decline. That decline has been concentrated among poor and working-class people.

When Valerie was growing up near a small village east of Bryan, her family used to shop at a locally owned grocery store that carried fresh fruits, vegetables, and meat. Now the shell of that store is sinking into a crumbling parking lot. A few yards down the road, a Dollar General welcomes shoppers. Dollar stores have become ubiquitous in rural and distressed urban landscapes as Wall Street investors have used their financial power to build thousands of the stores across the country, driving small independent grocers out of business. But dollar stores don’t carry many healthy foods. As a result, almost half of Williams County residents live in census tracts with nowhere to buy nutritious groceries.

“We don’t know what to do”

Bryan’s mayor, Carrie Schlade, grew up nearby. In her 41 years of living in the area, she has seen disturbing changes. Bryan doesn’t have as bad a drug problem as other parts of Ohio, but it does have one—mostly meth, heroin, and fentanyl. The number of kids in foster care because their parents used drugs has grown “exponentially” since the recession, she says.

Schlade believes something has gone wrong with the culture of the place. People are angry, or sad and angry, or resigned. Or something. She worries about mental health. She worries that too many people can’t seem to cope with even simple things, like getting up and going to work, and she worries about the state of Bryan’s housing stock, much of which is old and shabby on the east side of town, and she worries about the resentment she has encountered there.

Not that Schlade, the town’s first female mayor, is giving up. She and city leaders have managed to have the entire east side designated by the state as an area in which prospective employers could get tax breaks for opening a facility. She has been trying to support local churches that were doing good work running food pantries and teaching people how to manage money. She is always looking for state or federal grants to improve the community.

Sometimes Schlade despairs at such efforts. “We just don’t know what to do,” she once told me. “We know we’re fly-over country,” she said—so she reckoned rejuvenation was up to Bryan itself: “It’s like, ‘All right, we’ve been asleep long enough. It’s time to wake up. It is our job as a community to make our community good or bad. It is our choice.’”

It wasn’t their choice, though, not really—no more than it was their choice to shut down ARO. Outside forces had mined such communities for assets, pushing them into decay, and outside forces are required to help them back.

Plotting the road back

In early 2020, Jim Watkins, the chief of the Williams County health department, began a project with a group from Bowling Green State University and the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland to see what might be done to improve the county’s housing and living conditions. The plan, which had just taken its first steps when the covid-19 pandemic stalled it, aimed to develop policies and financing so people could maintain their homes, the community could develop better building codes and enforce them, blight could be removed from business districts, and community features could be created or improved to attract the public.

Bartik, the labor economist, is a skeptic of tax incentives like the ones given to Menards. He says that the cost per job is too high, and starves governments of money needed to fund education and other public goods. So he’s come up with a series of plans he calls “place-based job policies.”

In November of last year, Bartik proposed an $18.8 billion package of federal aid that would cover 30% of the US population in distressed and near-distressed labor markets. The plan would finance block grants so local areas could adapt the programs. Rather than simply trying to bribe businesses with tax incentives, he proposes more targeted programs. For instance, wage subsidies would enable employers to take on the risk of hiring apprentices, a practice that used to be common but is now rare in the United States. Neighborhood-based job training and placement services would help people living in distressed areas. Low- or no-interest loans to buy or repair cars would help people get to work. Subsidized child care would cut down on absences and ease the minds of workers.

Jobs have to pay more. Ohio’s minimum wage is only $8.80 an hour. The national minimum wage is just $7.25 and hasn’t risen since 2009. President Biden has proposed raising it to $15 per hour, which would be better, though still a low bar.

About 10% percent of Americans live in areas without access to broadband internet. Many who do have access can’t afford to pay for it. Expanding access and affordability could encourage entrepreneurs to think about starting businesses in places like Bryan, with its low cost of living.

This type of regional development could give towns like Bryan a draw they would not otherwise enjoy. Bartik cites the biggest regional development project in US history, the Tennessee Valley Authority, as an example. If such aid were effective, younger people would move to places like Bryan, says Brian Dabson, a research fellow at the University of North Carolina. “When you interview young people,” he says, “it’s surprising the portion of them who say, ‘We would come back if there was something we could do here.’”

No initiative, no program, no development aid will, by itself, solve the deepest problem of all: distrust of American institutions. Reagan told Americans that government was not the solution, it was the problem. That notion has since become a religion to many people in places like Bryan, their faith buoyed by failures they see around them. The internet’s capacity to spread mistrust, hate, division, and misinformation has helped discredit not just government, but also science and academia. The countervailing forces that can combat misinformation—literature, art, logic, critical thinking, civics, and history—have meanwhile been deemphasized in education in favor of “workforce development.” In February 2020, Ohio’s state superintendent of schools, Paolo DeMaria, changed the requirements for high school graduation: students would no longer have to achieve a proficient rating in either math or English. DeMaria set the standard in consultation with industry.

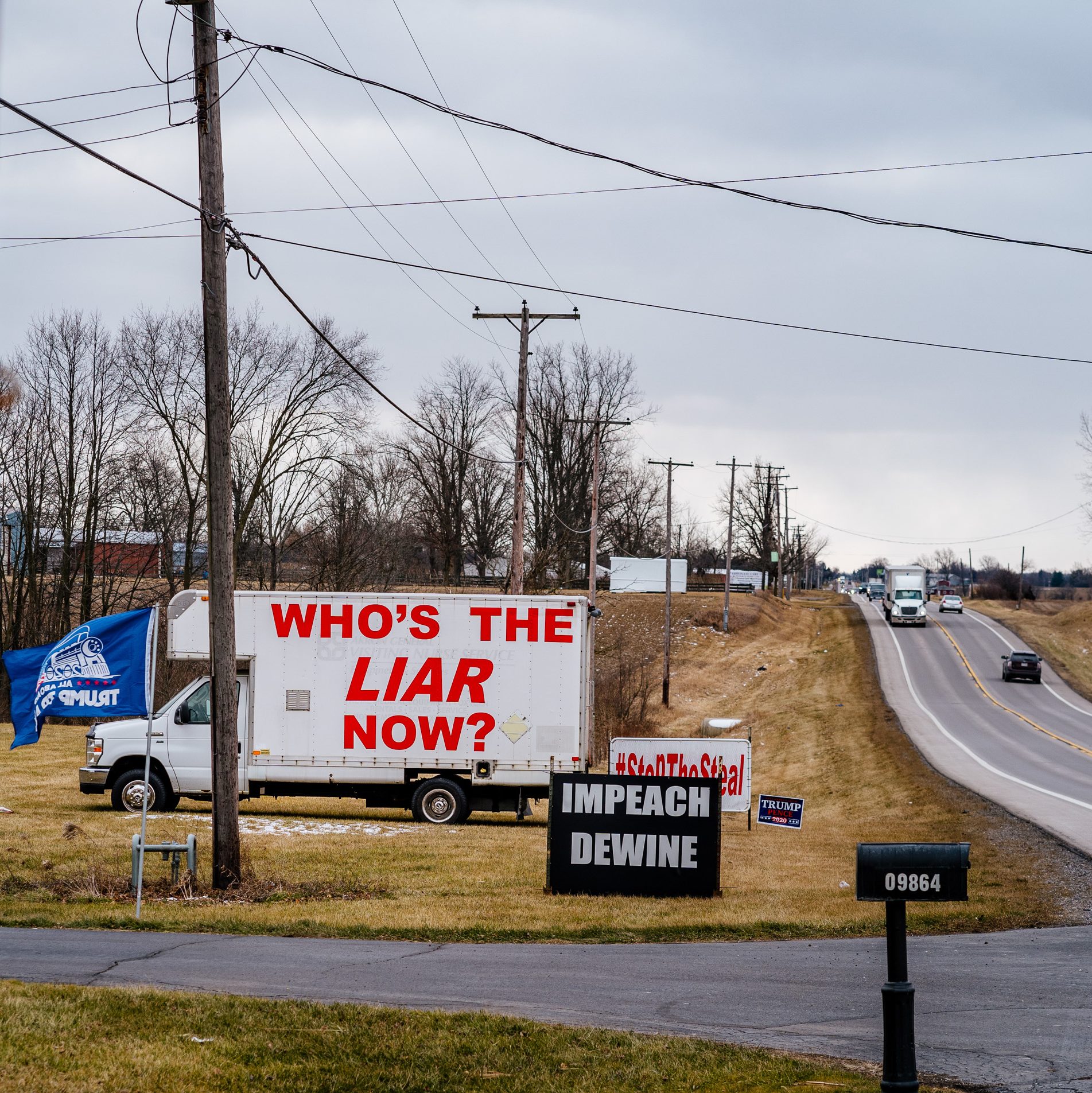

The pandemic has only exacerbated distrust that has been building for years. Some in Williams County denied the seriousness of covid-19. One village mayor insisted that masks actually spread the disease. Watkins, the public health chief, found himself battling covid-19 doubters. Amy Acton, Ohio’s state health director, was driven from office in 2020 by threats. County health chiefs around the state have needed police protection. On January 24, 2021, shots were fired at a state health official’s home.

The distrust and denial of truth and common sense only make it tougher for science- and technology-based businesses to picture themselves in places like Bryan. Unless there is deep and lasting investment in education sufficient to renew a faith in the possibility of rational progress, such areas can look forward to a future of low-paying, insecure jobs in warehouses and distribution centers, along with a handful of legacy manufacturers.

That means times will remain hard for people like Valerie Moreno, who recently wound up underemployed, again. She gave up her two part-time jobs and finally got some sleep, but then, two days before Christmas, she was laid off by Sauder. She quickly took a new part-time job with a home health agency while she spent the better part of a month fighting Ohio’s unemployment system. She still hadn’t received anything as of mid-January. Now Valerie struggles to maintain her own faith. “I take one day at a time,” she told me. “I don’t look too far in advance. I count my blessings every day.”

Parts of this article were adopted from the author’s forthcoming book, The Hospital: Life, Death, and Dollars in a Small American Town.