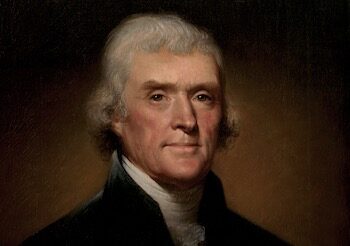

Balancing Innovation and Competition: Thomas Jefferson’s View of Obviousness for Mechanical Inventions

“Jefferson’s letter to [Isaac] McPherson showed that he weighed the marginal contribution of an invention against basic, foundational technologies, keeping in mind that a mere change of form—like changing fashions—should not be patentable.”

You cannot get a patent for an invention if it would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time. This is as true today as it was at the founding of our nation. The reason for this rule is clear—the obviousness-bar is necessary to balance rewarding innovation with free and fair competition. The Supreme Court has observed, alluding to the Constitution’s authorization for federal patents, “[w]ere it otherwise, patents might stifle, rather than promote, the progress of useful arts.” KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 427 (2007).

You cannot get a patent for an invention if it would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time. This is as true today as it was at the founding of our nation. The reason for this rule is clear—the obviousness-bar is necessary to balance rewarding innovation with free and fair competition. The Supreme Court has observed, alluding to the Constitution’s authorization for federal patents, “[w]ere it otherwise, patents might stifle, rather than promote, the progress of useful arts.” KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 427 (2007).

Achieving Balance

While we all agree that obvious inventions should not be patented, the devil is in the details on how to draw that line between the obvious and the nonobvious. Through experience and “slow progress” courts and practitioners have advanced the delicate art of obviousness argumentation. Graham v. John Deere Co. of Kansas City, 383 U.S. 1, 10 (1966). All the while, the Supreme Court has cautioned, as it did in KSR, that the doctrine of obviousness “must not be confined within a test or formulation too constrained [or rigid] to serve its purposes.”

Today it seems that the courts, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and the bar have found sound, flexible ways to ensure free and fair competition within the useful arts of software and chemistry. The Supreme Court’s omnipresent precedent in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, though controversial, ensures that abstract ideas—the basic building blocks of science—are not monopolized, especially through software or business method patents. And drawing inspiration from the Supreme Court’s demand in KSR for flexibility in obviousness, the USPTO has given its examiners extensive guidance and frameworks that are particularly useful for applying the doctrine of obviousness to chemical inventions. These frameworks enable flexibility in considering patent applications directed to new combinations of chemical ingredients, changing proportions in solutions, and even alterations in ingredients’ molecular structure. Instead, here, I will focus on the obviousness of mechanical inventions.

Getting Crowded

To be sure, the law of obviousness is routinely applied to mechanical inventions, as with all others. The USPTO has provided its examiners with guidance to allow rejection of inventors’ assertions of innovation through choice of materials or simple rearrangement or elimination of parts of known devices. Still, I have witnessed an overabundant proliferation of patenting in some mechanical fields. For some types of simple mechanical devices, there seem to arise vast thickets of patents. Canny practitioners have been successful in writing patent claims that distinguish their inventions over other mechanical devices by employing detailed descriptions of parts—a “flange” here, a “member” there – in which very slight structural differences become all-important “elements” of claims. Never mind that they are all slightly different arrangements to accomplish something well-known; the patent attorney will argue, “show me why this or that physical ‘element’ was known or obvious.” These arguments often prove successful at the USPTO or in court, leading to more and more crowding of the “art” in a given field and iteratively hemming in the competition and prospective manufacturing newcomers alike.

A Revealing Letter

When I encounter these thickets of mechanical device patents, I often benefit from going back to first principles, the founding era of America’s patent laws, and Thomas Jefferson. After ratification of the Constitution in 1789, the first Congress enacted the nation’s first Patent Act in 1790. Patents applications were to be considered by the “Commissioners for the Promotion of Useful Arts” (a proto-Patent Office), who originally were to be designated by the Secretary of State, the Secretary of War, and the Attorney General (Graham). As George Washington’s Secretary of State, Jefferson became this commission’s “moving spirit” and the “first administrator of our patent system.”

Years later, after serving under Washington and completing his own presidential administration, Jefferson wrote a letter about patents to Isaac McPherson in 1813. This letter has become historically famous, mostly for Jefferson’s more lofty discussion of intellectual property. Quotations from this letter are almost universally from Jefferson’s so-called “fire metaphor” and his observation that an invention must be significant to be “worth to the public the embarrassment of an exclusive patent.” But it is also interesting to consider the particular occasion and circumstances of the letter itself for its bearing on mechanical patents.

Isaac McPherson had originally written to Jefferson because a notorious inventor named Oliver Evans was threatening to sue him on his patents for “Elevators, Conveyers, and Hopper-boys.” When the Patent Act was passed, Evans was one of the first in the country to apply for and receive patents from Washington’s cabinet (Jefferson, along with Henry Knox and Edmund Randolph). As President, Jefferson himself had signed a law reviving and extending the term of some of Evans’ patents. Later, Evans’ agents traversed the country demanding royalties from perceived infringers. One of these agents even visited Jefferson, making the accusation that his agricultural equipment at Monticello infringed on Evans’ patents. Jefferson settled for Evans’ “moderate patent price,” but McPherson was seeking Jefferson’s advice on how to put up a fight against Evans’ claims.

In the letter, Jefferson gave McPherson a detailed explanation for why he thought some of Evans’ later patents were invalid. Jefferson believed that Evans’ grain elevator invention was obvious, based on “simple machinery [that] has been in use from time immemorial.” He discussed the similarities of Evans’ device with basic water-bucket elevators used for wells going back to the time of Rome, Archimedes’ screw pump, and a device called the “Persian wheel,” which was known from Egypt and the Barbary coast since 1727. He also discussed some textbooks and colonial prior art from Virginia farmers, including a machine that he himself had used for a long time for “Benni seed…Indian corn, and…wheat.” Jefferson believed these examples ought to “flash conviction both on reason and the senses, that there is nothing new in [Evans’] elevators.”

Jefferson told McPherson that, even if there were some structural distinctions between Evans’ invention and the prior art, that should not entitle him to a patent. In Jefferson’s opinion, “a mere change of form should give no right to a patent. [A]s a high quartered shoe, instead of a low one, a round hat, instead of three square, or a square bucket instead of a round one. But for this rule, all the changes of fashion in dress would have been under the tax of patentees.”

McPherson used Jefferson’s letter and other aspects of his investigation to petition Congress to cancel Evans’ patent. He submitted to Congress a report entitled “Memorial to the Congress of Sundry Citizens of the United States, Praying Relief from the Oppressive Operations of Oliver Evans’ Patent.” Congress ultimately did not act on it, but I find Jefferson’s advice remains helpful today.

Let’s Avoid Future Nuisances

Jefferson’s letter to McPherson showed that he weighed the marginal contribution of an invention against basic, foundational technologies, keeping in mind that a mere change of form—like changing fashions—should not be patentable. Applying this flexible approach to obviousness in the area of mechanical inventions might prevent patent thickets and enable fair competition, lower barriers to entry, and decrease prices. Otherwise, the mechanical patents of today have the potential to raise nuisances similar to the software patents so ubiquitously sued upon.