As regulation trumps innovation again, will F1 ever produce another breakthrough? · RaceFans

The greatest advance in Formula 1 technology during the last 50 years was arguably the arrival of carbon fibre chassis in 1981 – pioneered by John Barnard, then technical director of McLaren during the early eighties. In one swoop he revealed that was faster, lighter and safer than its competitors. The MP4/1 turned F1 upside-down: out when cutting, shutting and welding; in came the space age.

No alloy car would win another title, and since June 1982 only four Formula 1 drivers have suffered fatal injuries in a grand prix car. Barnard later admitted his peers “thought we were mad”, while the legendary Lotus design genius Colin Chapman doubted a sufficiently strong (read ‘safe’) car could be built from heated composite strands.

Thus, the introduction of carbon fibre chassis took immense courage on the part of Barnard. Indeed, until John Watson comprehensively proved the ‘crash-ability’ of such a complex structure at Monza in 1981 by stepping out of his destroyed car, there were widespread doubts about the safety of such chassis.

Tellingly, the wreckage was put on display at the headquarters of Hercules Aerospace – who provided technical expertise to McLaren – to demonstrate the strength of composites structures.

The latest – but unlikely to be the last – driver to benefit from Barnard’s vision was Romain Grosjean last November in Bahrain. True, as outlined here a number of factors contributed to the Haas driver’s ability to step almost unscathed from his burning car, but the immense strength of its carbon composite monocoque no doubt played a critical role.

Fast forward 20 years and imagine Barnard introducing the structure to F1 during pre-season testing. Imagine the constant bickering, shouts of illegality, complaints that composites are not in F1’s DNA, claims that such constructions are unsafe; above, calls for bans of such materials on cost grounds amid claims that all teams would be forced to switch to composites, thereby levelling the playing field, but at great cost to all.

Technical directive ‘clarifying’ that ‘material’ referred to in Article 123.abc actually refer to metallic substances and that unless welding in some form is present such chassis are deemed to be unsafe would follow. If such ‘clarifications’ cannot be implemented with immediate effect, then by the soonest possible date. Over-exaggerations, perhaps, but you get the drift…

Within a decade of MP4/1 McLaren commenced developing its F1 road car – still the benchmark by which supercars are measured – while carbon fibre chassis and components have increasingly found their way into structural and aesthetic applications in production cars on account of both their integrity and lightness.

Around a decade after Barnard’s composite brainwave, Williams fitted a continuously variable transmission – which uses belts and inverted cones to provide an almost infinite number of (step-less) gear ratios – to a FW15. According to a source – a specialist in pre-select gearboxes who was consulted by technical director Patrick Head – the car was two seconds per lap faster than the (already dominant) standard car around Pembrey, Wales.

This advantage immediately set alarm bells ringing in the paddock; worse, the engine’s incessant drone – revs barely rose as car speeds increased – made for ‘boring’ soundtracks. CVT was summarily banned through regulation changes for 1994 via clauses that demanded between “four and seven gears”, with a sub-clause specifically outlawing CVT by demanding stepped gear changes.

Fast forward again: Under Article 9.8.3 the 2021 technical regulations specify ‘The number of forward gear ratios must be 8’, adding ‘The minimum possible gear the driver is able to select must remain fixed whilst the car is moving’ and ‘Multiple gear changes may only be made under Article 5.21 or when a shift to gearbox neutral is made following a request from the driver.’

These articles have implications beyond CVT as they also effectively outlaw double shift gearboxes of the type fitted to a number of road vehicles, be they high performance sports cars, econoboxes or in between. Although the jury is out as to which is the faster shifter – DSG or F1’s ubiquitous sequential transmissions, which have little road car relevance – the question cannot be answered for regulatory reasons.

The irony is, though, that various hybrid road cars are now specified with CVT, with Bosch currently developing CVTs specifically for battery electric cars. Imagine how much more efficient CVTs and DSGs would be were F1 encouraged to develop such system rather than insist on the blind alley that is sequential shifters.

Ditto hybrid technology: In 1998 Adrian Newey, then at McLaren, devised an energy recovery system in conjunction with Mario Illien, at the time technical head of the team’s engine supplier, Mercedes. The system would deliver a lap time advantage of 0.2 seconds they calculated, so the pair checked out its legality with the FIA. It was given the green light, so the pair set about developing the first KERS for F1.

Then energy recovery systems were abruptly banned – on the grounds that F1 cars were permitted only one propulsion system, which of course it does with KERS which merely harvests energy created by previous propulsion – with a full banning clause enshrined in the 1999 technical regulations.

Then, exactly ten years later the FIA – headed by the same president (Max Mosley) – provided for (optional) 80bhp KERS systems as part of the governing growing ‘green’ awareness, yet Toyota, at the time the world’s hybrid drive leader refused to develop such a system on the grounds that the system fitted its Prius was more sophisticated. Newey, by then with Red Bull, also declined, but on weight grounds.

However, from 2013 onwards the electrical portion was doubled, while, as revealed here, F1 is planning for up to 300bhp in hybrid power from 2025. Imagine how much more advanced such systems would by now be without initial regulatory interference.

Massed outcries were heard a year ago after Mercedes introduced dual axis steering; previously McLaren’s so-called ‘F-duct’ caused similar controversies, as did Brawn’s double-deck diffuser – both were banned. Yet, the F-duct made a camouflaged return as DRS and 2025’s cars will likely feature elaborate diffusers.

Some form of front-rear-interconnected suspension – banned by “clarification” in 2014 after costly development programmes – is likely to return then, too, as active suspension. FRIC was originally introduced to provide aerodynamic stability via self-levelling platforms, but similar technologies have found their way into road cars – think Citroen – for load and comfort purposes. Thus, road relevance exists, yet FRIC is illegal.

F1 prides itself on (allegedly) being at the cutting edge of technical innovation, yet virtually every advance finds itself banned at the earliest opportunity, whether on technical, sporting or financial grounds. Should any or all of these reasons fail to outlaw a development, then the old fall-backs – detrimental to the ‘show’ – or unending, loud criticism will surely do so.

In most instances the ‘reasons’ forwarded simply mask fears that the competition has created a legal advantage through ingenuity and creativity. F1 needs to learn that genuine competition is vital to the sport’s future, whether these contest are staged on-track or enacted in engineering offices, on mainframes in wind tunnels or autoclaves.

Consider F1’s engine freeze: Where once non-stop development was F1’s calling card, from 2022 teams are stuck for three years with ‘frozen’ engines largely based on 2012 architecture – which was devised before Tesla sold its first Model S! That said, at the time these turbocharged 1.6-litre hybrids should have been feted as marvellous examples of hi-tech engineering able to deliver faster lap times than their (KERS’d 2.4-litre V8) predecessors on 30% less fuel.

Instead, virtually every paddock figure without an engine division maligned them publicly or refused to provide any details. I recall asking the CEO of an F1 powertrain supplier in 2016 about his product’s thermal efficiencies – the benchmark for engine design. Before he could respond – and thus I have no way of knowing what the answer would be – his PR minder intervened and closed off the topic.

Consider: the company was spending upwards of $300 million annually on its F1 engine operation in order to generate marketing ink and acquire technical expertise in a complex field, yet the most crucial number, the one with by far the biggest ‘wow’ factor, was kept hidden from the media – and thus fans – probably for reasons of confidentiality. Yet any opposition supplier worth its salt knew the numbers in any event!

This secrecy was not, though, maintained for long: around two years later the company abruptly U-turned and proudly bandied about its efficiency indices to all and sundry. Whatever happened in the interim is anybody’s guess, but clearly the company’s policies (and philosophies) changed for the better.

Saliently, when RaceFans approached the four current engine suppliers last week for visuals of their latest F1 engines, we received a range of different examples. Ferrari supplied the most recent imagery, a screengrab showing their 2020 power unit.

Honda provided the most up-to-date photograph – the picture below is of their 2019 engine. Mercedes offered a 2016 photograph on the basis that it was the latest approved image. Renault provided a picture of their original Energy F1 power unit from 2014.

Make of this what you like about their $300m engine programmes…

Remote ‘garages’ – which enable teams to operate with fewer on-site personnel by linking circuit to base via teleconferencing and telemetry – were recently under threat, allegedly on ‘cost’ grounds. Once the affected teams had proved the technologies were revenue spinners via sponsorships the authorities relented.

Covid has since imposed strict and challenging workplace regimes on F1; imagine where the sport would be had remote working been so myopically outlawed.

All these examples and many more – such ABS, traction control, active suspension, wing cars, turbochargers (banned, then embraced again) slick tyres (ditto) – sprang to mind when a technical directive about so-called ‘bendy wings’ was issued to teams last week. While there are no suggestions that the innovations listed above were invented by or in F1, there are few doubts that such technologies benefitted vastly F1 applications.

Flexible wings reduce drag by presenting ‘flatter’ aerodynamic surfaces at speed, thus boosting speeds on straights before returning to their original positions under braking. What is wrong with that, save that some teams haven’t mastered the technologies or cannot afford them – possibly both?

Such materials are, though, the future in a variety of industries ranging from automotive applications through medical and electronics products to consumer items, with F1 being ideally poised to both develop and showcase such technologies on a global stage, yet it seems that whenever innovations stick their head above the pit wall they are stamped upon, whether by teams, the governing body or commercial rights holder.

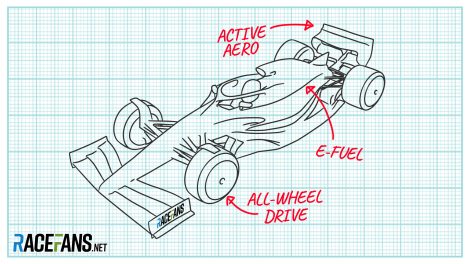

Curiously, in a recent interview for RaceFans F1 chief technical officer Pat Symonds revealed that active aerodynamics are under consideration for F1’s 2025-onwards formula – which has sustainable fuels and increased electrification as its corner stones, making drag reduction imperative if F1 is to maintain (or exceed) impressive lap speeds.

“You don’t have to be an engineer to realise that one of the reasons we use quite a lot of fuel on these cars is because they’re high drag,” Symonds said. “So, the first thing you’ve got to do, apart from the fact that you’re moving into much more hybridisation, is get some drag out of it. That leads you to active aerodynamics on the car.”

Why, then, ban flexible materials now when all the heavy spending has already been incurred? There are no doubts that F1 has crucial roles to play in the wider world, as FIA president Jean Todt stated in the foreword of the recent Futerra study into motorsport’s contributions to society.

“Advances on the racetrack find their way to the road, helping to preserve lives and the planet,” he said. “This has probably never been as clear as in the response of the community to the global pandemic this year. While motor racing is back on track, providing entertainment for millions of fans, it remains a laboratory for a better future.”

By definition motorsport – in particular F1 – can, though, only be a laboratory if it is granted the freedom to continue developing relevant technologies. Stifling competition for fear of being beaten is a one-way ticket to oblivion.