Letter to SEC: How Stock Buybacks Undermine Investment in Innovation for the Sake of Stock-Price Manipulation | naked capitalism

Jerri-Lynn here. Grab a cup of coffee. William Lazonick’s latest on stock buybacks – which Biden promised to address during the presidential campaigning hasn’t (see for further context, Where Did You Go, Vice President Joe? Biden Retreats from Bashing Looting, Um, Buybacks).

In this comprehensive post, Lazonick and co-author Ken Jacobsen analyse how: “ Rule 10b-18, as originally written in 1982 and revised by the Commission in 2003, has in fact undermined capital formation by business corporations in the U.S. economy.” [By providing a safe-harbour and thus enabling stock-price manipulation], “the Rule has contributed to growing inequality in the distribution of income in the United States, with consequences that are economically destructive, socially dangerous, and morally reprehensible. For these reasons we recommend that the Commission rescind Rule 10b-18.”

By William Lazonick Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts Lowell and President, The Academic-Industry Research Network and Ken Jacobsen, Director of Communications, The Academic Industry Research Network, Director of Communications, The Academic Industry Research Network. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

A comment on the Securities and Exchange Commission’s proposed rule “Share Repurchase Disclosure Modernization”

April 1, 2022

Vanessa Countryman, Secretary

Securities and Exchange Commission

100 F St NE

Washington, DC 20549

Re: Share Repurchase Disclosure Modernization (File No. S7-21-21)

Secretary Countryman,

We are writing to comment on Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed rule “Share Repurchase Disclosure Modernization” (SEC Release Nos. 34-93783; IC-34440; File No. S7-21-21), published in the Federal Register of February 15, 2022.

William Lazonick is president of the Academic-Industry Research Network (AIRnet), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research organization, and University of Massachusetts professor of economics emeritus. Ken Jacobson is the AIRnet communications director. As AIRnet members, both of us are regularly engaged in research and writing on questions of industrial innovation, corporate financialization, and economic performance. This public comment is complementary to William Lazonick, “Investing In Innovation,” an INET Working Paper, also submitted as a public comment under File No. S7-21-21.

The proposed rule’s stated purpose is “to modernize and improve disclosure”[1] covering repurchases made by an issuer of its stock. We have been engaged in in-depth scholarly investigation into the stock market’s role in the operation and performance of the U.S. economy in general as well as the circumstances surrounding the adoption and impacts of Rule 10b-18 by the Securities and Exchange Commission on November 17, 1982, in particular. As the result of this research, we have no doubt that the adoption of Rule 10b-18 in 1982 was based on a fundamental misidentification of the primary source of funds for capital formation by publicly listed business corporations in the United States.

As we argue in this public comment, Rule 10b-18, as originally written in 1982 and revised by the Commission in 2003, has in fact undermined capital formation by business corporations in the U.S. economy. In giving issuing corporations a safe harbor against stock-price manipulation charges, Rule 10b-18 has enabled them to execute many trillions of dollars in open-market repurchases (OMRs) since the mid-1980s—including an estimated $5.4 trillion by corporations in the S&P 500 Index in the decade 2012-2021 alone. As we outline in this comment, our research demonstrates both theoretically and empirically that Rule 10b-18 has enabled stock-price manipulation while undermining capital formation in the United States. In the process, the Rule has contributed to growing inequality in the distribution of income in the United States, with consequences that are economically destructive, socially dangerous, and morally reprehensible. For these reasons we recommend that the Commission rescind Rule 10b-18.

The Commission’s uncritical acceptance of shareholder primacy as the corporation’s purpose

The proposed amendments to Rule 10b-18 contemplated by Share Repurchase Disclosure Modernization (File No. S7-21-21) do not remedy these fundamental problems of Rule 10b-18. The principal change effected by the proposed rule would be to increase the timeliness and specificity of information available to both shareholders and the Commission by requiring that issuing corporations disclose to the Commission by the end of the following business day[2] each day’s: total number of shares repurchased; total number of shares repurchased on the open market; and average price paid per share.[3] Currently, disclosure is required only four times a year, at the end of each quarter, with repurchases reported in totals aggregated by month.

The proposed rule would also require, for the first time, disclosure by a repurchaser of:

According to the Commission, these requirements were based on responses to a previous request for comments and are “intended to improve investor access to information regarding the rationale and objectives of any issuer repurchase plan,”[5] as well as to “allow investors to better understand how an issuer has structured its repurchase plan and whether it has taken steps to prevent officers and directors from potentially benefiting from issuer repurchase in a manner that is not available to regular investors.”[6]

From our point of view, the question overhanging this proposed rule is not whether officers and directors should be stopped from benefiting unfairly from some issuer repurchases, but whether they should not be stopped from doing issuer repurchases at all. The SEC appears to assume without reservation that, as it states in the proposed rule, “[g]enerally, there are legitimate business reasons for issuers to repurchase securities,”[7] and it sees this legitimacy as resting on whether these repurchases are “aligned with shareholder value maximization.”[8] But the Commission fails to question the actual consequences of issuer repurchases—and, indeed, of shareholder value maximization—for the welfare of the public and of those shareholders who have long-term goals, both groups being among those it is sworn to protect, and in so failing it is abdicating key responsibilities set out in its charter.

Further evidence of the SEC’s oblivion of, or disregard for, essential parts of its mandate is to be found in the fact that, in the rule’s discussion of the enhanced disclosure it proposes, the question “How would investors use this information?”[9] is repeatedly asked, while there is not one mention of how it might be used by the Commission itself. One among the new points of disclosure, referred to 17 times in the proposed rule (and cited above), is the reporting of issuer repurchases made in reliance on the Rule 10b-18 non-exclusive safe harbor.[10] Again the question posed in the proposed rule is “Would investors benefit” from such requirements as this reporting, again left totally aside is the issue of whether the SEC’s own enforcement staff might benefit from it—even though former SEC Chair Mary Jo White admitted in 2015 that “[p]erforming data analyses for issuer stock repurchases presents significant challenges because detailed trading data regarding repurchases is not currently available.”[11] and even though the proposed rule marks the first time that increasing disclosure has been mooted since then.

Rule 10b-18 undermines capital formation and encourages stock-price manipulation

The theoretical perspective underpinning the adoption of Rule 10b-18, rooted in the neoclassical theory of the market economy,[12] is that the stock market allocates financial resources to their most efficient uses, and hence open-market issuer share repurchases, as permitted by Rule 10b-18, perform that allocative function. The problem is that the theory of the firm in which the argument is rooted lacks any explanation of: a) how particular business firms generate higher-quality, lower-cost products than those previously available, providing the firm with a productivity advantage on the markets in which it competes; and b) how the “most efficient uses” that the neoclassical theory of the market economy takes as given come to into existence.[13] From the perspective of “the Theory of Innovative Enterprise” (TIE), developed by William Lazonick and colleagues over the past four decades, the primary source of corporate funds for investing in innovation—that is, capital formation that can generate higher-quality, lower-cost products—is that portion of the firms’ profits that it retains over time.[14]

We should be clear on the critical point that what we mean by “capital formation” includes the firm’s investment in human capabilities as well as physical facilities. The essence of the innovation process is organizational learning to transform technologies and access markets. The firm’s employees engage in this learning collectively both at specific points in time and cumulatively over time. In combination with investing in plant and equipment (commonly called “capital expenditures”), the innovating firm invests in training and retaining its employees, with most of that training occurring through uninterrupted on-the-job experience. The prime source of finance for investment in human capabilities is retained earnings that the firm allocates from current profits a) to reward employees in the form of wage and benefit increases for their contributions of skill and effort to generating those profits, and b) to afford employees the opportunity to engage in collective and cumulative learning through investment strategies that can potentially develop the firm’s next generation of innovative products. These corporate investments in human capabilities are recorded to some extent in research and development (R&D) expenditures but go beyond them to include organizational learning in all the functional and hierarchical activities of the business enterprise (note that only about 40 percent of companies included in the S&P 500 Index show any R&D expenditures at all, yet all of the firms have to some extent invested in organizational learning). These corporate investments in human capabilities are essential not only to firm-level innovation but also to national productivity growth that can provide the foundation for our society to have a strong and expansive middle class.

We accept that a publicly listed corporation should pay a portion of its profits to shareholders in the form of dividends when these distributions do not impinge on the earnings required for its capital formation. We also accept that there may be legitimate ways in which a company might repurchase its own shares. One is through tender offers. Another is through open-market repurchases (OMRs) made to acquire shares for special funds kept in segregated accounts for distributions to employees—a common practice among U.S. business corporations in the decades prior to the adoption of Rule 10b-18, and one that, for example, Amazon employed when it did $1.8 billion in OMRs from 2006 to 2012.[15] But, in providing a company with a safe harbor against charges of stock-price manipulation if the amount of stock repurchased does not exceed 25 percent of the average daily trading volume (ADTV) on a single trading day, Rule 10b-18 in effect gives a company permission to manipulate its stock price.

In 1997 buybacks, as repurchases are commonly known, first surpassed dividends in the U.S. economy, and buybacks have far exceeded dividends in recent stock-market booms.[16] As a form of distribution to shareholders, buybacks done on the open-market are much more volatile than dividends, the former booming when stock prices are high. For the 216 companies in the S&P 500 Index in January 202 publicly listed over the years 1981-2019, in 1981-1983 buybacks absorbed 4.4 percent of net income and dividends another 49.7 percent. But in 2017-2019, buybacks for the same 216 companies were 62.2 percent of net income and dividends 49.6 percent.[17]

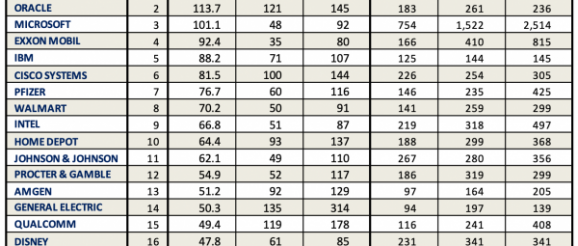

Table 1 shows the ADTV amounts covered by the Rule 10b-18 safe harbor for the 20 largest share repurchasers among U.S. industrial corporations in the decade 2010-2019 on three dates: October 21, 2019, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic; June 23, 2020, in the midst of the pandemic; and March 28, 2022, the first trading day of the week during which we are submitting this comment. Note that under Rule 10b-18, a corporation can avail itself of a safe harbor against manipulation charges in doing share repurchases of these magnitudes trading day after trading day. Of these 20 companies, 13 distributed more than 100 percent of net income to shareholders over the decade 2010-2019, while the other seven distributed 75 percent or more.[18]

Table 1: Twenty largest stock repurchasers, 2010-2019, among U.S. industrial corporations and their SEC Rule 10b-18 safe-harbor average daily trading volume (ADTV) amounts for repurchases on 10/21/19, 06/23/21, and 03/28/22

Notes: BB=stock buybacks; DV=cash dividends; NI=net income; ADTV=average daily trading volume limit to secure the safe harbor against stock-price manipulation charges under SEC Rule 10b-18.

Sources: Company 10-K and 10-Q filings with the SEC; Yahoo Finance daily historical stock prices.

Note that some stock buybacks are carried out as accelerated share repurchases (ASRs), in which an issuing company enters into a contract with a bank under which the bank is to repurchase a certain value of the issuer’s shares over a certain period of time. For example, on February 7, 2019, Pfizer entered into a $6.8 billion ASR agreement with Goldman Sachs, to be completed by August 1, 2019. On signing the contract, the bank borrows shares equal to the value of the ASR contract from asset managers who are not interested in selling the shares. Then, over the term of the ASR contract, the bank executes OMRs at its discretion—presumably for amounts that remain with the 25% ADTV safe-harbor limit on any given trading day—and gives the borrowed shares back to the asset managers. But, on the date on which it signs the ASR contract, the issuing company reduces its number of shares outstanding by the entire amount of the ASR (in the case of Pfizer, by $6.8 billion), thus giving an immediate—“accelerated”—boost to its earnings-per-share (EPS) without transgressing the ADTV safe harbor limit under Rule 10b-18.

More generally, our research has identified a four-stage “buyback process” through which OMRs can boost a company’s stock price at the following junctures: 1) when the company announces a program to do share repurchases; 2) when the firm’s broker actually executes the buybacks on the open market, which may be done trading day after trading day; 3) when the upward momentum that buybacks give to a company’s stock price is reinforced by market speculation that the stock-price increase will continue; and 4) when the company releases its quarterly earnings report, with buybacks resulting in a higher EPS and P/E Ratio, even if earnings (i.e., net income) have failed to increase. These four stages in the buyback process can reinforce one another in lifting a company’s stock price. And innovation plays absolutely no role as a driver of the company’s enhanced stock-price “performance.”

The flawed assumptions of “maximizing shareholder value” and the role of Rule 10b-18

The Commission’s uncritical acceptance of “maximizing shareholder value” (MSV), evident in the proposed rule change under consideration here, betrays its apparent failure to recognize the extent to which Rule 10b-18 undermines investment in innovation by U.S. industrial corporations and permits stock-price manipulation. In fact, on a subject that we have studied intensively,[19]the adoption of Rule 10b-18 in November 1982 played a leading role in the rise of MSV as an ideology of “predatory value extraction” (to use the title of 2020 book by William Lazonick and Jang-Sup Shin).[20] The adoption of Rule 10b-18 in 1982 occurred two or three years before MSV became a widely articulated perspective on the purpose of the corporation, as evidenced, for example, by hits on the term “shareholder value” in the business press, which only began appearing in large numbers in the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times in 1985.[21] In 1981, the Business Roundtable (BRT) had issued a statement that proclaimed value creation for multiple stakeholdersas the purpose of the corporation, and it was not until 1997—the year, as it happened, in which stock buybacks first surpassed dividends as a mode of distribution to shareholders in the U.S. corporate economy—that the BRT declared its adherence to a “shareholder primacy” view of the purpose of the corporation.[22] Nearly a quarter century later, with substantial publicity and 181 CEO signatories, the BRT reverted in August 2019 to a stakeholder perspective on the purpose of the corporation, which it reaffirmed in August 2021.[23]

Given that in 2021 companies in the S&P 500 Index, many of whose CEOs were signatories to the BRT 2019 statement of purpose, did a combined $882 billion in share repurchases, one might justifiably conclude that the corporate commitment to stakeholder capitalism is more rhetoric than reality in the United States. Nevertheless, there is certainly no consensus in business, government, or academia that, as an ideology of corporate governance, MSV in fact supports the allocation of the economy’s resources to their most efficient uses. Over the decades, there have been a number of cogent academic critiques of MSV, including our own, which contend that the pursuit of MSV prioritizes value extraction from companies for the benefit of shareholders at the expense of investing in the capabilities other stakeholders, particularly employees, to reward and further enable their contributions to corporate value creation.[24] It is therefore curious, and from our perspective dismaying and even bizarre, that, as a government agency in service of the public, the Commission is, in the year 2022, considering amendments to Rule 10b-18 through the prism of MSV.

A key event in the emergence of MSV as a widely accepted ideology of corporate governance during the last half of the 1980s was the 1985 hiring as a professor at Harvard Business School (HBS) of Michael C. Jensen, at that time the foremost proponent of this perspective among a group of economists known as “agency theorists.” One of the authors of this comment, William Lazonick, who was then a member of the HBS faculty, can attest to the fact that in 1984 “shareholder value” was not central to the school’s research and teaching, whereas from 1985, under the academic leadership of Jensen, it emerged as the dominant HBS perspective.

Jensen, who had obtained his PhD from the University of Chicago in 1968, had been inspired by a 1970 New York Times article by Chicago economist Milton Friedman on shareholder primacy to write his 1976 paper with William Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” which introduced “agency theory” as an argument for the efficiency of MSV in the allocation of the economy’s resources.[25]Subsequently, Jensen’s most influential academic articles in making the case for MSV were “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers” (1986) and, with Kevin J. Murphy, “Performance Pay and Top Management Incentives” (1990).[26]

We can get a clear insight into understanding the fundamental flaws of MSV by focusing our attention on the explicitly stated context in which, in September 1970, the New York Times Magazine published Friedman’s article, “The Social Responsibility of a Business Is to Increase Its Profits.”[27] As it appeared in the magazine, the article displayed a photo of General Motors Chairman James Roche at the company’s annual general meeting in May 1970, with editorial text explaining that he was replying “to members of Campaign G.M.,” accompanied by photos of eight of them wearing “Tame G.M” buttons. Campaign G.M. had submitted a shareholder proposal to General Motors’ annual meeting to include three “public interest” members on the company’s board of directors for the purpose of advocating for safer and more fuel-efficient cars. [28] The proposal garnered little shareholder support, but General Motors announced in August that, in response to Campaign G.M., it had set up a five-person committee of existing board members to study the matters of car safety and fuel efficiency.

In an introductory comment published with Friedman’s article, a New York Times editor referred to the shareholders’ meeting in May 1970 and its aftermath, making the reason for the magazine’s publication of the article, as well as its timing, absolutely clear. As the editor wrote:

Representatives of Campaign G.M. demanded that G.M. name three new directors to represent “the public interest” and set up a committee to study the company’s performance in such areas of public concern as safety and pollution. The stockholders defeated the proposals overwhelmingly, but management, apparently in response to the second demand, recently named five directors to a “public-policy committee.” The author [Milton Friedman] calls such drives for social responsibility in business “pure and unadulterated socialism,” adding: “Businessmen who talk this way are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of free society.”

In retrospect, the demands of Campaign G.M. that the car company produce safer and less-polluting cars were demands for General Motors to engage in automobile innovation.[29] In the 1970s and beyond, the world leaders in producing these “socially responsible” cars would be Japanese and European companies, leaving the “profit-maximizing” General Motors lagging further and further behind in terms of product quality and market share. What, in 1970, Friedman called “pure and unadulterated socialism” proved to be the innovative future of the automobile industry!

The “Friedman doctrine,” as annunciated in his New York Times article, became the clarion call for companies to be run to “maximize shareholder value” over the following decades. In the pre-MSV era in which Friedman published his article, profitable U.S. business corporations distributed ample dividends to shareholders while also adhering to the norm of a career with one company for both blue-collar (often unionized) and white-collar (typically college educated) employees, manifested by long employment tenures with defined-benefit retirement pensions based on years of service with the company. Under this corporate-governance regime, during the post-World War II decades U.S. industrial corporations had emerged as global leaders while, within the United States, the distribution of income had shown a trend toward somewhat more equality. Indeed, at the beginning of the 1970s, the U.S. distribution of income among households was less unequal than at any other time in the nation’s history. Fundamental to these outcomes was the regime of corporate resource allocation that we call “retain-and-reinvest”: U.S. business corporations retained a substantial proportion of their profits and reinvested them in the productive capabilities of their labor force.

Beyond Friedman’s rant about “pure and unadulterated socialism” and business executives who were “the unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of free society,” Jensenite agency theory, elaborated in the quarter century after the 1976 publication of the Jensen and Meckling article, was to give academic legitimacy to a regime of corporate resource allocation that we call “downsize-and-distribute”: in the name of MSV as a purported engine of economic efficiency, the corporation downsizes its labor force and distributes cash to shareholders in the form of not only dividends but also buybacks.

Jensen and Meckling’s central proposition in “Theory of the Firm” is that, as the firm’s principals, shareholders are “residual claimants” who take the risk of whether or not the funds that they have invested in the firm will generate profit (i.e., a residual of revenue over cost). The “agency problem,” they argue, is to find ways to incentivize corporate managers to behave in the interests of the company’s shareholders, thus mitigating the agency cost of the principal-agent relation. In the 1980s and 1990s, Jensen advocated the use of stock-based pay to incentivize senior executives to “disgorge” the so-called “free cash flow” in the form of buybacks and dividends.[30] The term “disgorge” implies that the cash is somehow ill-gotten and therefore does not belong in the corporation, ignoring the sources of value creation that result in profit as well as the role of retentions out of profit as the financial foundation for the firm’s renewed investment in productive capabilities. Moreover, it is the MSV argument itself that defines what part of cash flow is “free”—even if increasing that part comes at the cost of laying off thousands of employees to be able to do billions of dollars in buybacks with the intent of manipulating the company’s stock price. From the MSV perspective, reinvestment of corporate profit in a company that shares the gains of innovation with workers represents, as Jensen put it, “wasting [corporate cash] on organizational inefficiencies.”[31]

In short, as articulated by Jensen and others, MSV is an ideology of value extraction posing as a theory of value creation that is rooted in two misconceptions of the role of public shareholders in the U.S. business corporation. Its most fundamental error is the assumption that public shareholders invest in the productive assets of the corporation. They do not.[32] They allocate their savings to the purchase of shares outstanding on the stock market because the liquidity of the stock market enables them to sell those financial securities at any time they so choose. The erroneous MSV assumption that public shareholders invest in the company’s productive assets is compounded by the fallacy that it is only public shareholders who make risky investments in the corporation’s productive assets, and hence that it is only shareholders who have a claim on the corporation’s profit, if and when it occurs.

Public shareholders are portfolio investors, not direct investors. The generation of innovative products requires direct investment in productive capabilities. These investments in innovation are uncertain, collective, and cumulative. Innovative enterprise requires strategic control to confront uncertainty, organizational integration to engage in collective learning, and financial commitment to sustain cumulative learning. Public shareholders provide none of these functions. To understand the productivity of the firm, we need a theory of innovative enterprise.

When, as in the case of a startup, financiers make equity investments in the absence of a liquid market for the company’s shares, they are direct investors who face the risk that the firm will not be able to generate a competitive product. The existence of a highly speculative and liquid stock market may enable them to reap financial returns—in some cases, even before a competitive product has been produced. It was to make such a speculative and liquid market available to private-equity investors, who were to become known as “venture capitalists,” that in 1971 the National Association of Security Dealers Automated Quotation (NASDAQ) system was launched to link electronically the previously fragmented, and hence relatively illiquid, Over-the-Counter markets in quoting national stock prices. NASDAQ became an inducement to direct investment in startups precisely because it offered venture capitalists the prospect of a quick “exit” from their direct investment through an initial public offering (IPO) that could take place within a few years after the founding of the firm.[33]

In effect, venture capitalists exit their illiquid, high-risk direct investments by turning them into liquid, low-risk portfolio investments. If, after an IPO, the former direct investors decide to hold onto their shares, they are precisely in the same low-risk portfolio-investor position as any other public shareholder; they can use the stock market to buy and sell shares whenever they so choose.

But venture capitalists as private-equity investors are not the only economic actors who bear the risk of making direct investments in productive capabilities. Households as taxpayers through government agencies, and households as workers through the business firms that employ them, make risky investments in productive capabilities on a regular basis. From this perspective, households as both taxpayers and workers may have, by agency theory’s own logic, “residual claimant” status—that is, an economic claim on the distribution of corporate profit, if and when it occurs.

Through government investments and subsidies, taxpayers regularly provide productive resources to companies without a guaranteed return. As risk bearers, taxpayers who fund such investments in the knowledge base, or in physical infrastructure such as public roads that businesses use, have a claim on corporate profit if and when it is generated. Through the tax system, governments, representing households as taxpayers, seek to extract this return from corporations that, through the products that they sell, reap the rewards of government spending.

In financing investments in knowledge and infrastructure, therefore, taxpayers make productive capabilities available to business enterprises, but with no guaranteed return on those investments. At any given corporate tax rate, households as taxpayers face the risk that, because of technological, market, and competitive uncertainties, the enterprise will not generate the profit that provides business tax revenues as a return to households as taxpayers on their investments in infrastructure and knowledge. Moreover, tax rates are politically determined. Households as taxpayers face the political uncertainty that predatory value extractors may convince government policymakers that unless businesses are given tax cuts and financial subsidies that will permit adequate profit, they will not be able to make value-creating investments. Corporate executives and wealthy households may put politicians in power who accede to these demands for tax cuts and financial subsidies.

Workers regularly make productive contributions to the companies for which they work through the exercise of skill and effort beyond those levels required to lay claim to their current pay, but without guaranteed returns.[34] An employer who is seeking to generate a higher-quality, lower-cost product enables employees to engage in organizational learning through which they can build their careers, thereby putting themselves in a position to reap future remuneration in work and in retirement. Yet these careers and the returns that they can generate are not guaranteed, and under the downsize-and-distribute resource-allocation regime that MSV ideology and agency theory have helped put in place, these returns and careers have, in fact, been undermined.

Therefore, in supplying their skills and efforts to the process of generating innovative products that, if successful, can create value in the future, workers take the risk that the application of their skills and the expenditure of their efforts will be in vain. Far from reaping expected gains in the form of higher pay, more job security, superior benefits, and better working conditions, workers may face cuts in pay and benefits if the firm’s innovative investment strategy does not succeed, and they may even find themselves laid off. Workers also face the possibility that, even if the innovation process is successful, the institutional environment in which MSV prevails will empower corporate executives, encouraged by hedge-fund activists, to cut some workers’ wages and lay off others in order to extract value for shareholders, including themselves. Much of the value that executives and activists extract is value that the skills and efforts of employees helped to create.

The irony of MSV is that the public shareholders whom agency theory holds up as the only risk bearers typically never invest in the value-creating capabilities of the company at all. Rather, they purchase outstanding corporate equities with the expectation that, while they are holding the shares, dividend income will be forthcoming, and with the hope that, when they decide to sell the shares, the stock-market price will have risen to yield a capital gain. Following the directives of MSV, a prime way in which the executives who control corporate resource allocation fuel this expectation is by allocating corporate cash to stock buybacks to pump up their company’s stock price.

Those holding onto their shares will receive cash dividends, while those wishing to sell their shares will stand a chance of reaping enhanced financial gains at buyback-inflated stock prices—if they get the timing of their stock sales right. Neoclassical economists assume that, via financial markets, the gains from dividends and cash from stock sales will be allocated to uses that are more efficient than if the funds had been retained by the company. They make this claim, however, without a theory of innovative enterprise that can explain how, through strategy, organization, and finance, a company creates value. In practice, agency theory advocates predatory value extraction, legitimized by the erroneous and ideological belief that public shareholders invest in productive capabilities and, indeed, that public shareholders are the only participants in the firm who make productive contributions without a guaranteed return.

Proponents of MSV may accept that a company needs to retain some cash flow to maintain its physical capital. But they view labor as an interchangeable commodity that can be hired and fired, as needed, on the labor market. And they ignore the contributions that, through government agencies, households as taxpayers make to business-value creation. Rather, as espoused by Jensen and Murphy in their 1990 article, agency theorists look to stock options and stock awards as means of aligning the incentives of senior executives with the corporate purpose of MSV.

When, from the last half of the 1980s, Jensen and his followers, teaching at major business schools, exhorted current and future corporate executives to “maximize shareholder value” by disgorging the free cash flow, they were not merely touting a theoretical possibility in the disposition of corporate cash. To the contrary, ready at hand was SEC Rule 10b-18, which permitted U.S. business corporations to do massive stock buybacks as OMRs, often in addition to generous dividend payouts. There is a very important difference between dividends and buybacks as modes of distributing corporate cash to shareholders. Dividends are paid to all shareholders as a yield for, as the name says, holding their shares. In the case of buybacks, those who realize the gains are sharesellers—including Wall Street bankers, hedge-fund managers, and, with their stock-based pay, corporate executives—who are in the business of timing the buying and selling of shares. Rule 10b-18 provides these “predatory value extractors” with a powerful, and legalized, tool to manipulate the stock market for their own personal benefit, even if—as Lazonick put it in the subtitle of his 2014 Harvard Business Review article, “Profits Without Prosperity”—it “leaves most Americans worse off.”

The formulation and adoption of Rule 10b-18

Encouraging stock buybacks is what proposed rule 10b-18 appears to have been intended to do. In a 1984 article, “Issuer Repurchases,” Lloyd H. Feller, an associate director of the SEC’s Division of Market Regulation in the late 1970s, and Mary Chamberlin, an official of that Division when Rule 10b-18 was adopted, pointed to “the almost complete change in the Commission’s regulatory attitude toward issuer repurchases” that its adoption marked. They characterized SEC proposals for rules regulating buybacks, put forward as Rule 13e-2 in 1970, 1973, and 1980, as “emphasizing all the incentives an issuer may have to influence improperly the market for its stock,” But Rule 10b-18, they noted, “focused on the need to avoid intrusive regulation,” its “sole purpose” having been stated by the agency “as providing certainty to issuers” that there were measures they could take “in connection with repurchase programs so that they could avoid ‘what otherwise might be a substantial and unpredictable risk’ of liability under the antifraud and antimanipulative provisions of the federal securities laws.”[35] This shift in outlook, termed in the article’s subtitle “a Regulatory About-Face,”[36] was a key component of the SEC’s Reagan-era transformation from regulator of securities markets, the agency’s primary function since its creation under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, to promoter of stock-market activity.

The transition did not go entirely smoothly. Recounting the November 9, 1982, public meeting at which the Commission voted to adopt Rule 10b-18, a Wall Street Journal article cited a “sharp protest” from Commissioner John Evans, a 1973 appointee of President Nixon. In reacting to the easing in repurchase regulation, Evans complained that “there will be some manipulation” that would go unprosecuted and added: “This is much-reduced regulation from what we had before.” A high-ranking member of the SEC staff not only acknowledged the possible validity of Evans’s objection; he went so far as to quantify the extent to which he expected enforcement would be diminished: by 10 percent to 20 percent. Rule 10b-18 “preserves our ability to pursue 80% to 90% of the manipulation cases we have historically brought,” predicted Market Regulation Division Director Douglas Scarff, offering that miscreants could be ensnared by rules violations often associated with manipulation, such as making false statements during a securities transaction.[37]

Pushing the change through, the SEC’s Reagan-appointed chairman, John Shad, stated that buybacks “confer a material benefit” on a company’s shareholders, by (in the words of WSJ reporter Richard Hudson) “fueling increases in market stock prices.” Hudson reported Shad’s concern that without the change companies would be “inhibited” from making big open-market buys. In the end, Evans agreed, in the interest of unanimity, to vote for the rule but said he was doing so “with some concern.”[38]

On the day Rule 10b-18 was officially adopted, November 17, 1982, Proposed Rule 13e-2 was definitively withdrawn, with an explanation by the SEC that it had “determined that mandatory regulation” of issuer repurchases was “not necessary.”[39] The new rule could not have presented a sharper contrast to its aborted predecessor. As proposed, Rule 13e-2 would have been a “per serule”:[40] that is, as it was constructed, Rule 13e-2 considered any action it “proscribed” to be inherently illegal—or, to translate the Latin, illegal “in itself”—and those who committed the action to be breaking the law. It was for this reason that the SEC had described the form of regulation embodied by Rule 13e-2 as “mandatory.” Rule 10b-18, on the other hand, makes nothing illegal. Instead, it exempts companies from charges of manipulation under other rules and statutes if they stay within the boundaries of the four provisions—comprising volume limitations, timing limitations, price limitations, and a single broker-dealer limitation—that delimit what is referred to as a “safe harbor.” At the same time, Rule 10b-18 refrains from any presumption that transgressing the safe harbor’s boundaries constitutes an illegal act.[41]

The circumstances surrounding the withdrawal of Proposed Rule 13e-2 and the adoption, without either prior notice or public comment, of Rule 10b-18 are somewhat perplexing in their own right. The SEC, in its official announcement of 10b-18’s adoption, dismissed in a footnote its having dispensed with the public notice and subsequent comment period that constitute a standard step in federal rule-making procedure: “In view of the fact that the provisions of the safe harbor afforded by Rule 10b-18 are substantially similar to the provisions of proposed Rule 13e-2 that would have been imposed on a mandatory basis and for which there has already been substantial public comment, the Commission has determined that further notice and comment are not necessary.”[42]

This is puzzling for three reasons. The first is that omitting a comment period appears in and of itself to be a violation of the 5 U.S. Code § 533, the relevant provision of the Administrative Procedure Act. Since violations of rule-making requirements can be redressed only through a lawsuit brought by an injured party, it is possible that the SEC decided simply to roll the dice, figuring that because Rule 10b-18 was less stringent than proposed Rule 13e-2, those acquainted with and interested in issuer repurchases—broker-dealers, investment houses, and the issuers themselves—would be unlikely to react to liberalizing changes by bringing suit.[43]

It is also possible that the staff took encouragement from the comments that the agency had received in response to the release of the 1980 version of Proposed Rule 13e-2, and, in fact, the release announcing the 1982 adoption of Rule 10b-18 is peppered with suggestions from “commentators” criticizing various aspects of 13e-2. “[T]he securities industry and various bar associations urged the Commission to consider whether there continued to be a need for the rule,” according to a near-contemporary account. “In particular, they pointed out that the record of demonstrated misconduct in the area over the past decade was sparse.”[44] It is, however, impossible for more recent researchers to take any measure of the general sentiment of the commentators, as the folder in which SEC records indicated they were stored was found, in October 2014, to contain only a one-page receipt indicating that the file’s contents had gone out from the National Archives and Records Administration on “temporary loan” to an “authorized SEC requestor” on a date no later than October 4, 1993.

A second reason for puzzlement is that the grounds on which the SEC claimed that there had been no need for notice and comment in the case of then-Proposed Rule 10b-18—that its provisions and those of Proposed Rule 13e-2 were “substantially similar”—tests credulity. The Commission had, in fact, expressly rejected the institution of a safe harbor in presenting the 1980 version of 13e-2:

Some commentators on the 1973 Proposal suggested that the rule should be drafted as a ‘safe harbor’ from liability under the antifraud and anti-manipulative provisions of the federal securities laws such as Section 10(b) (and Rule 10b-5) and Section 9(a)(2) of the Act. Although these commentators discussed certain policy considerations for structuring the rule as a safe harbor, their suggestion appeared in large measure to be based on questions relating to the Commission’s authority to adopt a rule that would prescribe specific requirements, such as the time and price limitations, as means designed to prevent fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative acts and practices. As discussed above, the Commission believes that Section 13(e) provides the authority to adopt the rule as proposed. Moreover, as a policy matter, the Commission is concerned that the suggested ‘safe harbor’ approach would not sufficiently deter improper issuer conduct. The standards embodied in the proposed rule, particularly the volume limitations, are likely to be the most confining in the cases where they may also be the most needed, i.e., in their application to issuers whose securities are thinly-traded. Particularly in view of the difficulty in many instances of proving whether a manipulation has or has not in fact occurred, the purposes sought to be achieved by the proposed rule would likely not be achieved if the rule were only a safe harbor and the issuer were free to engage in transactions that exceeded the rule’s limits.[45]

It is hard to understand how the Commission could find a regulatory approach that it had judged entirely inadequate to be “substantially similar” to the one it was instituting a scant two years thereafter.

Finally, the discrepancy in the volume limitation between 15 percent in Proposed Rule 13e-2 and 25 percent in Rule 10b-18 hardly seems insubstantial. The authors of the well-known legal treatise Securities Regulation found the loosening of the limitation curious in itself, while also calling into question the basis on which it was made:

[E]ven in securities that are so thinly traded that block trades are unlikely, the allowance of 25 percent of trading volume, rather than the earlier proposed 15 percent, alone is question begging. Rule 10b-18 gives issuers and affiliated purchasers a safe harbor from liability for stock price manipulation. It does not seem unreasonable to assume that the larger the percentage of issuer or affiliated purchaser trading volume allowed by this safe harbor, the greater the likelihood that actual manipulation will be shielded. Nonetheless the entire explanation of the 25 percent ceiling was a statement, without citation or other support, that “[t]he Commission has concluded that a 25% purchasing condition is appropriate in that Commission cases concerning manipulation in the context of issuer repurchases have historically involved conduct outside the conditions of Rule 10b-18, including a volume limitation of 25%.”[46]

In a forthcoming paper, we provide an explanation of the origins of the 15% ADTV in Rule 13e-2. Suffice it to observe here that, given the 25% ADTV limits shown in Table 1, even 15% ADTV would have permitted major manipulation of stock prices. But, under the provisions of Proposed Rule 13e-2, at least transgression of the limit would have been known to the Commission and manipulation charges could have been lodged. As former SEC Chair Mary Jo White wrote to Sen. Tammy Baldwin, a company cannot violate Rule 10b-18; it can only avail itself of the Rule’s safe harbor against manipulation charges.[47]

The fact is that the Commission has never claimed that OMRs of the magnitude of 25% ADTV shown in Table 1 do not manipulate stock prices. Rather, Rule 10b-18 simply states that a company that remains within that limit will not be charged with manipulation. In fact, since the mid-1980s, as our research has shown, Rule 10b-18 has functioned as a license to loot the corporate treasury, with highly adverse impacts on investment in innovation, employment opportunity, and income distribution. The Commission should rescind Rule 10b-18.

Sincerely,

William Lazonick

[7] Ibid., p. 8446.

[8] Ibid., p. 8444, 8454, 8455, 8460. Conversely, the proposed rule speaks of “compensation arrangements [that] can…incentivize executives to undertake repurchases, in an attempt to maximize their compensation, even if such repurchases are not optimal from the shareholder maximization perspective” – again indicating that buybacks’ being in harmony with shareholder value maximization is considered the bedrock of their legitimacy. Ibid., pp. 8454-55 [emphasis added].

[9] Ibid., pp. 8449 (twice), 8450 (thrice),

[10] E.g., Ibid., p.8461: “Would investors benefit from the proposed requirement to disclose additional detail about the number of shares repurchased on the open market, the number of shares repurchased in reliance on the safe harbor in Rule 10b-18, and the number of shares repurchased pursuant to a plan intended to satisfy the affirmative defense conditions of Rule 10b5-(c)?”

[11] Mary Jo White, Letter to U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin, July 13, 2015, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2272283-sec-response-to-baldwin-07132015.

[12] William Lazonick, “Is the Most Unproductive Firm the Foundation of the Most Efficient Economy? Penrosian Learning Confronts the Neoclassical Fallacy,” International Review of Applied Economics, 36, 2, 2022: 1-32.

[13] William Lazonick, “The Theory of Innovative Enterprise: Foundations of Economic Analysis,” in Thomas Clarke, Justin O’Brien, and Charles R. T. O’Kelley, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Corporation, Oxford University Press, 2019: 490-514, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198737063.013.12.

[14] William Lazonick, Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, Harvard University Press, 1990; William Lazonick, Business Organization and the Myth of the Market Economy, Cambridge University Press, 1991; William Lazonick and Mary O’Sullivan, eds., Corporate Governance and Sustainable Prosperity, Palgrave, 2002; William Lazonick, Sustainable Prosperity in the New Economy? Business Organization and High-tech Employment in the United States, W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2009, ch. 5, https://doi.org/10.17848/9781441639851; William Lazonick, “Labor in the Twenty-First Century: The Top 0.1% and the Disappearing Middle Class,” in Christian E. Weller, ed., Inequality, Uncertainty, and Opportunity: The Varied and Growing Role of Finance in Labor Relations, Cornell University Press, 2015: 143-192; William Lazonick and Jang-Sup Shin, Predatory Value Extraction: How the Looting of the Business Corporation Became the US Norm and How Sustainable Prosperity Can Be Restored, Oxford University Press, 2020; William Lazonick, “Investing in Innovation: A Policy Framework for Attaining Sustainable Prosperity in the United States,” Institute for New Economic Thinking Working Paper No. 182 March 30, 2022, https://www.ineteconomics.org/research/research-papers/investing-in-innovation-a-policy-framework-for-attaining-sustainable-prosperity-in-the-united-states, submitted as a public comment on Share Repurchase Disclosure Modernization (File No. S7-21-21) on April 1, 2022.

[15] Ken Jacobson and William Lazonick, “License to Loot: Opposing Views of Capital Formation and the Adoption of SEC Rule 10b-18,” The Academic-Industry Research Network, forthcoming 2022; William Lazonick, “The secret of Amazons success,” New York Times, November 19, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/19/opinion/amazon-bezos-hq2.html.

[16] William Lazonick, “Stock Buybacks: From Retain-and-Reinvest to Downsize-and-Distribute,” Center for Effective Public Management, Brookings Institution, April 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/research/stock-buybacks-from-retain-and-reinvest-to-downsize-and-distribute/; pp. 10–11; William Lazonick, Mustafa Erdem Sakinç, and Matt Hopkins, “Why Stock Buybacks are Dangerous for the Economy,” Harvard Business Review, January 7, 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/01/why-stock-buybacks-are-dangerous-for-the-economy?ab=hero-subleft-.

[17] For a graphic presentation and discussion of these data, see Lazonick, “Investing in Innovation,” pp. 13-14.

[18] For further data and analysis of corporate resource allocation, see Lazonick, “Investing in Innovation,” pp. 19-26.

[19] William Lazonick, “Profits Without Prosperity: Stock Buybacks Manipulate the Market and Leave Most Americans Worse Off,” Harvard Business Review, September 2014, pp 46-55; William Lazonick, “Stock Buybacks: From Retain-and-Reinvest to Downsize-and-Distribute, ” Center for Effective Public Management, Brookings Institution, April 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/research/stock-buybacks-from-retain-and-reinvest-to-downsize-and-distribute/; William Lazonick, “Innovative Enterprise and Sustainable Prosperity,” paper presented at the annual conference of the Institute for New Economic Thinking, Edinburgh, October 10, 2017, https://www.ineteconomics.org/research/research-papers/innovative-enterprise-and-sustainable-prosperity; William Lazonick, “The Value-Extracting CEO: How Executive Stock-Based Pay Undermines Investment in Productive Capabilities,” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 48, 2019: 53–68; Lazonick and Shin, Predatory Value Extraction; Jacobson and Lazonick, “License to Loot.”

[20] Lazonick and Shin, Predatory Value Extraction.

[21] See Johan Heilbron, Jochem Verheul, and Sander Quak, “The Origins and Early Diffusion of ‘Shareholder Value’ in the United States,” Theory and Society, 43, 1, 2014: 1-22; Marion Fourcade and Rakesh Khurana, “>span class=”reftitleJournal”>History of Political Economy, 49, 2, 2017: 347–381.

[22] Ken Jacobson, “Whose Corporations? Our Corporations!,” Huffington Post, April 5, 2012, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/whose-corporations-our-co_b_1405832.

[23] Business Roundtable, “Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of the Corporation to Promote ‘An Economy That Serves All Americans’,” press release, August 19, 2019, ; Business Roundtable, “Business Roundtable Marks Second Anniversary of Statement on the Purpose of the Corporation,” press release, August 19, 2021.

[24] See, for example, Margaret Blair, Ownership and Control: Rethinking Corporate Governance for the Twenty-First Century, Brookings Institution Press, 1995; Lynn Stout, The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the Public, Berrett-Koehler, 2012; Mary A. O’Sullivan, Contests for Corporate Control: Corporate Governance and Economic Performance in the United States and Germany, Oxford University Press, 2000; Thomas Clarke, ed, Theories of Corporate Governance, Routledge, 2004; Ciaran Driver and Grahame Thompson, eds., Corporate Governance in Contention, Oxford University Press, 2018. For our critiques, see William Lazonick, “Controlling the Market for Corporate Control: The Historical Significance of Managerial Capitalism,” Industrial and Corporate Change, 1, 3, 1992: 445-488; William Lazonick and Mary O’Sullivan, “Maximizing Shareholder Value: A New Ideology for Corporate Governance,” Economy and Society, 29, 1, 2000: 13-35; Lazonick, “Innovative Enterprise and Sustainable Prosperity”; William Lazonick and Ken Jacobson, “How Stock Buybacks Undermine Sustainable Prosperity,” The American Prospect, March 13, 2019, https://prospect.org/economy/stock-buybacks-undermine-sustainable-prosperity/; Lazonick, “Is the Most Unproductive Firm the Foundation of the Most Efficient Economy?; Lazonick and Shin, Predatory Value Extraction; Lenore Palladino and William Lazonick, “Regulating Stock Buybacks: The $6.3 Trillion Question,” International Review of Applied Economics, under revision 2022.

[25] Michael C. Jensen and William H. Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 4, 1976: 305-360.

[26] Michael C. Jensen, “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers,” American Economic Review, 76, 2, 1986: 323-329 (the term “disgorge” is used on pages 323 and 328); Michael C. Jensen and Kevin J. Murphy, “Performance Pay and Top Management Incentives” Journal of Political Economy, 98, 2, 1990: 225-264.

[27] Milton Friedman, “A Friedman doctrine—The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1970.

[28] Donald E. Schwartz, “Proxy Power and Social Goals—How Campaign GM Succeeded,” St. John’s Law Review, 45, 4 1971, Article 9

[29] Michael Olenick, “Original Shareholder Value Article—Milton Friedman to GM: Build Clunky Cars,“ Naked Capitalism, August 2, 2017, https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2017/08/original-shareholder-value-article-milton-friedman-gm-build-clunky-cars.html.

[30] Jensen, “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers”; Jensen and Murphy, “Performance Pay and Top Management Incentives.”

[32] William Lazonick, “The Functions of the Stock Market and the Fallacies of Shareholder Value,” in Ciaran Driver and Grahame Thompson, eds., What Next for Corporate Governance? Oxford University Press, 2018: 117-151. See, for example, William Lazonick, “Apple’s ‘Capital Return’ Program: Where Are the Patient Capitalist?” Institute for New Economic Thinking, November 13, 2018, https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/apples-capital-return-program-where-are-the-patient-capitalists.

[33] Lazonick, Sustainable Prosperity in the New Economy?, ch. 2.

[34] Lazonick, Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor; Lazonick, “Labor in the Twenty-First Century.”

[35] Lloyd H. Feller and Mary Chamberlin, “Issuer Repurchases,” Review of Securities Regulation, 17, 1, 1984: p. 996.

[37] Richard L. Hudson, “SEC eases way for repurchase of firms’ stock,” Wall Street Journal, November 10, 1982, p. 2.

[39] Securities and Exchange Commission, “Purchases of Equity Securities by Issuers,” 1982, Federal Register, Rules and Regulations, 47, 228, November 26, 1982: 53398.

[40] “Purchases of Certain Equity Securities by the Issuer and Others; Adoption of Safe Harbor” at 53334.

[41] “No presumption shall arise that an issuer or affiliated purchaser of an issuer has violated [the antimanipulative provisions of] Sections 9(a)(2) or 10(b) of the [1934] Act or Rule 10b-5 under the Act if the Rule 10b-18 bids or Rule 10-b8 purchases of such issuer or affiliated purchaser do not” comply with its four purchasing restrictions. Idem at 53341.

[42] “Purchases of Certain Equity Securities by the Issuer and Others; Adoption of Safe Harbor,” fn.4 at 53334.

[43] A number of people who were on or worked with the SEC staff at the time, when contacted personally for our research, maintained that either they had not been involved in the decision or had no recollection of the issue’s being discussed. Two of them, however, said it had been their understanding that, in general, the SEC considered public comment to be mandatory only when the approval of a rule being considered would render the regulatory regime stricter than it would have been under a previously proposed rule, while public comment could be dispensed with in the case of a proposed rule under which regulation would become more lenient.

[44] Feller and Chamberlin, “Issuer Repurchases,” p. 996.

[45]“Purchases of Certain Equity Securities by the Issuer and Others” at 70894 [emphasis added].

[46] Louis Loss, Joel Seligman, and Troy Paredes, Securities Regulation, 4thedition, vol. 10, Aspen Publishers/Wolters Kluwer Law & Business, 2006: 87-8, quoting Final Rule 10b-18.

[47] Mary Jo White, “Letter from SEC Chair Mary Jo White to Sen. Tammy Baldwin,” July 13, 2015, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2272283-sec-response-to-baldwin-07132015; David Dayen, David, “SEC admits it’s not monitoring stock buybacks to prevent market manipulation,” The Intercept, August 12, 2015, https://theintercept.com/2015/08/13/sec-admits-monitoring-stock-buybacks-prevent-market-manipulation/.