Another big step for quantum computing: A 20x improvement method to reset a quantum computer – Innovation Toronto

UNSW Sydney research demonstrates a 20x improvement in resetting a quantum bit to its ‘0’ state, using a modern version of the ‘Maxwell’s demon’.

A team of quantum engineers at UNSW Sydney has developed a method to reset a quantum computer – that is, to prepare a quantum bit in the ‘0’ state – with very high confidence, as needed for reliable quantum computations. The method is surprisingly simple: it is related to the old concept of ‘Maxwell’s demon’, an omniscient being that can separate a gas into hot and cold by watching the speed of the individual molecules.

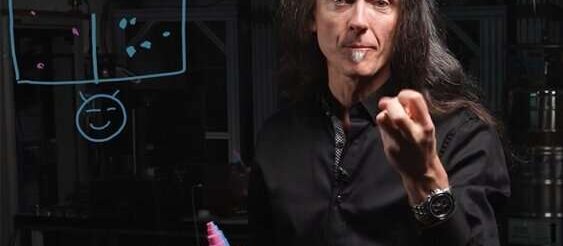

“Here we used a much more modern ‘demon’ – a fast digital voltmeter – to watch the temperature of an electron drawn at random from a warm pool of electrons. In doing so, we made it much colder than the pool it came from, and this corresponds to a high certainty of it being in the ‘0’ computational state,” says Professor Andrea Morello of UNSW, who led the team.

“Quantum computers are only useful if they can reach the final result with very low probability of errors. And one can have near-perfect quantum operations, but if the calculation started from the wrong code, the final result will be wrong too. Our digital ‘Maxwell’s demon’ gives us a 20x improvement in how accurately we can set the start of the computation.”

The research was published in Physical Review X, a journal published by the American Physical Society.

Watching an electron to make it colder

Prof. Morello’s team has pioneered the use of electron spins in silicon to encode and manipulate quantum information, and demonstrated record-high fidelity – that is, very low probability of errors – in performing quantum operations. The last remaining hurdle for efficient quantum computations with electrons was the fidelity of preparing the electron in a known state as the starting point of the calculation.

“The normal way to prepare the quantum state of an electron is go to extremely low temperatures, close to absolute zero, and hope that the electrons all relax to the low-energy ‘0’ state,” explains Dr Mark Johnson, the lead experimental author on the paper. “Unfortunately, even using the most powerful refrigerators, we still had a 20 per cent chance of preparing the electron in the ‘1’ state by mistake. That was not acceptable, we had to do better than that.”

Dr Johnson, a UNSW graduate in Electrical Engineering, decided to use a very fast digital measurement instrument to ‘watch’ the state of the electron, and use real-time decision-making processor within the instrument to decide whether to keep that electron and use it for further computations. The effect of this process was to reduce the probability of error from 20 per cent to 1 per cent.

A new spin on an old idea

“When we started writing up our results and thought about how best to explain them, we realized that what we had done was a modern twist on the old idea of the ‘Maxwell’s demon’,” Prof. Morello says.

The concept of ‘Maxwell’s demon’ dates back to 1867, when James Clerk Maxwell imagined a creature with the capacity to know the velocity of each individual molecule in a gas. He would take a box full of gas, with a dividing wall in the middle, and a door that can be opened and closed quickly. With his knowledge of each molecule’s speed, the demon can open the door to let the slow (cold) molecules pile up on one side, and the fast (hot) ones on the other.

“The demon was a thought experiment, to debate the possibility of violating the second law of thermodynamics, but of course no such demon ever existed,” Prof. Morello says.

“Now, using fast digital electronics, we have in some sense created one. We tasked him with the job of watching just one electron, and making sure it’s as cold as it can be. Here, ‘cold’ translates directly in it being in the ‘0’ state of the quantum computer we want to build and operate.”

The implications of this result are very important for the viability of quantum computers. Such a machine can be built with the ability to tolerate some errors, but only if they are sufficiently rare. The typical threshold for error tolerance is around 1 per cent. This applies to all errors, including preparation, operation, and readout of the final result.

This electronic version of a ‘Maxwell’s demon’ allowed the UNSW team to reduce the preparation errors twenty-fold, from 20 per cent to 1 per cent.

“Just by using a modern electronic instrument, with no additional complexity in the quantum hardware layer, we’ve been able to prepare our electron quantum bits within good enough accuracy to permit a reliable subsequent computation,” Dr Johnson says.

“This is an important result for the future of quantum computing. And it’s quite peculiar that it also represents the embodiment of an idea from 150 years ago!”