We need to measure innovation better. Here’s how | World Economic Forum

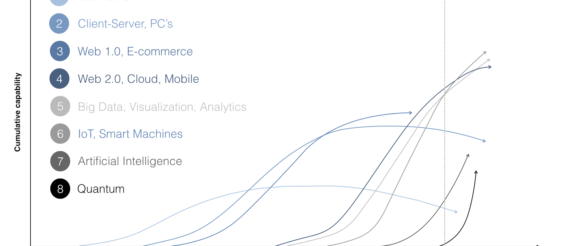

Innovation drives productivity, and productivity is what drives jobs growth and the wealth that pays for our health, education, defence and social security systems. In short, innovation really matters. Governments, businesses and academics obsess over it. We need to know what works, what doesn’t and why – and that means turning to measurements and metrics. But can we really measure innovation today? Are we doing it right, or are our metrics more suited to Industry 2.0 and 3.0, rather than 4.0?

Indicators have to account for many different forms of innovation, with widely differing motivations, processes of development and consequences. In the past it was possible to identify innovation within particular organizations, teams or individuals; nowadays innovation is more often networked among multiple contributors, which complicates its measurement. Collecting data on innovation is hampered by the desire to ensure indicators are simple, easily accessible, comparable across nations, and cheap to acquire and compute. And these requirements do not reflect the complex and often messy realities of innovation, let alone capture whether the innovation has negative consequences, such as putting CFCs in refrigerators.

The move over the past 60 years from products to services to an increasingly experiential economy has changed the nature of research and development (R&D). Traditional measures of innovation, such as R&D investment and patents, were fine when innovation mostly occurred in large manufacturing firms, but are of limited value when much of the action lies in services, business models, and entrepreneurial start-ups. Much innovation does not rely on traditional R&D investment and processes, and many innovations are not protected by formal intellectual property rights, but by the speed of changes and secrecy around them – and this makes them difficult to measure.

Other judgement calls are needed: are innovations new to the world, new to the sector or region, or just new to the firm? Is adapting an existing product or service to a new market an innovation? While these surveys can tell us about the ITALnumbers and ITALtypes of firms that claim to be innovative, they don’t address the more important question of ITALhow firms are innovating and whether this is improving.

The nature and measurement of capital goods – the assets that are put to productive use – have changed significantly in Industry 4.0. In the past, these consisted mainly of investments in large-scale factories and production machinery, and were carefully recorded for accounting and taxation purposes, providing accurate information for governments. Nowadays, intangible investments and activities such as design are much more significant – but these are more difficult to measure. The new digital technologies of Industry 4.0, including AI and Machine Learning, virtual and augmented reality, simulation and modelling methods, and novel, small-scale ways of manipulating matter such as additive manufacturing and genome editing, for example, complicate the recording and classifications of important innovation investments.

Data and digital science provide new opportunities for developing useful innovation metrics. Innovation statistics agencies are exploring the ways in which new sources of data can complement and supplement their work. Analysing social media sites and electronic marketplaces for ideas and employment, such as InnoCentive and LinkedIn, can provide valuable insights. While there are concerns about the self-selecting and potentially unrepresentative nature of the information collected, data-scraping and analytical tools can be used to provide useful new and real-time insights into innovation activity.

Companies such as Digital Science are using AI tools for mapping the trajectories of science, and these could be used for mapping innovation. Scientists have created algorithms and used machine learning to study complex and emerging phenomena such as health and weather forecasting, and these could be repurposed and applied to measuring innovation. Real understanding of innovation requires a deep dive into what goes on within organizations. It has to take into account how risks are assessed, decisions are made and implemented, and how the rocky roads of internal politics and organizational battles over resources are navigated. If government policy is to be informed, quantitative indicators of innovation performance must be complemented with qualitative case studies. For these case studies to be valuable they have to comply with formal research method protocols to ensure they are relevant, accurate and can be compared.

Government innovation policies have to be based upon, and directed towards improving, the performance and practices of the new industrial era. The way innovation occurs is changing – and so the indicators that measure it must respond to this new reality.