Groups Call for An End to ICE Arrests in Oregon Courthouses | Innovation Law Lab

Groups Call for An End to ICE Arrests in Oregon Courthouses

On September 18, 2017, ICE agents trailed and detained a county employee, father, and U.S. citizen as he and his wife left the Washington County courthouse. Mr. Isirdro Andrade Tafolla had grown up in the small community of Hillsboro, Oregon, now with a growing tech sector and one of the most diverse populations in Oregon. Mr. Andrade Tafolla was a star soccer player in high school, now a cherished soccer coach, and has worked as a dedicated county road maintenance worker for over twenty years.

A team of ICE agents were present in the courtroom when Mr. Andrade Tafolla and his wife, Renee Selden Andrade, arrived for a routine appearance. The agents then followed the couple and detained Mr. Andrade Tafolla just outside of the courthouse.

The agents were wearing street clothes, including college sweatshirts and jeans, and offered no badges, warrants or other identification. Driving three unmarked white minivans, they blocked the street to prevent Mr. Andrade Tafolla from leaving in his own vehicle. Here is the exchange:

ACLU Legal Observer: Do you have a warrant? Are you with ICE? Do you have a warrant for arrest? Do you have any identification; do you have any identification that you can show them?

[No response– second ICE agent steps in front of the Legal Observer]

ICE Agent (continues to Mr. Andrade Tafolla): What is your last name?… This picture right here [demonstrating a photo of another man] is you.

…

Mrs. Selden Andrade: You are not a part of the Court. We do not know you. Please back away from my husband, please back away from our car before we call the cops… That is not my husband.

…

ACLU Legal Observer: Does anybody have ID? Does anybody have a warrant?

Mrs. Selden Andrade: No.

…

Mrs. Selden Andrade: We need to call the police… these random people are approaching us. We have no idea who these people; we literally walked out of the courtroom and we are being approached.

Since 2017, the number of courthouse-related ICE intrusions like this one has skyrocketed. This unfortunate incident sadly repeats itself throughout the country, as unidentified ICE agents in plainclothes and unmarked cars increasingly use courthouses as a primary site for their deportation objectives. As in Mr. Andrade Tafolla’s case, the agency often relies on racial profiling to find its targets. The highly public nature of these arrests, and the attendant reporting, has caused widespread fear. Communities, judges, and elected officials across the country have condemned the practice, but it continues unabated. Just two weeks ago a single father and legal permanent resident was arrested and forcibly removed from the Oregon state courthouse halls while appearing for a minor charge.

Oregonians now join a growing chorus of voices demanding that state court leadership end ICE arrests in and around the courthouse to ensure that the halls of justice remain open to all, by asking for a uniform trial court rule prohibiting civil immigration arrests in and around state courthouses.

Reaching Back to Blackstone

Rewind to over a century ago, when famed trial lawyer Clarence Darrow petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to recognize a “very ancient” common law doctrine: the privilege against civil arrest at the courthouse. [1] Appealing to the “dignity and authority” of state and federal courts to administer “efficient and evenhanded administration of law and justice,” Darrow persuaded the Court that these arrests offend the judicial process itself. [2] The Stewart Court, quoting a case now two hundred years old, confirmed that fact:

“Courts of justice ought everywhere to be open, accessible, free from interruption, and to cast a perfect protection around every man who necessarily approaches them. The citizen in every claim of right which he exhibits, and every defense which he is obliged to make, should be permitted to approach them, not only without subjecting himself to evil, but even free from the fear of molestation or hindrance.”[3]

Key to the Court’s holding was the recognition that any deterrence of witnesses and parties may be just as damaging to the administration of justice as an arrest itself. Without the privilege against civil arrests, the Court reasoned, “witnesses would be [wary] of coming within our jurisdiction.”[4] The Court went on to recognize that that privilege extended not only within the walls of the courthouse, but also “in attendance upon court, and during a reasonable time in coming and going.”[5]

Fourteen years later, Oregon joined the vast majority of states in recognizing the common law privilege against civil arrests. Wemme v. Hurlburt affirmed that in Oregon “[p]arties and witnesses are exempt from arrest while going to, in attendance on, and returning from court. This exemption is not prescribed by statute, but is a part of the common law and is a power inherent in courts for the purpose of preventing delay, hindrance, or interference with the orderly administration of justice in the courts.”[6]

Oregonians Request Prompt Action from the Chief Justice

Now before Chief Justice Martha Walters of the Oregon Supreme Court is a similar petition to keep the state courthouse accessible to all Oregonians, immigrant and non-immigrant alike. Adelante Mujeres, Causa Oregon, Immigration Counseling Service, Metropolitan Public Defender, Northwest Workers’ Justice Project, Unite Oregon, and Victim Rights Law Center, represented by Innovation Law Lab and Nadia Dahab of Stoll Berne, are joined by the ACLU of Oregon and Youth, Rights & Justice in urging the Court to take action to protect the foundational rights of immigrants, and more broadly, every individual utilizing the courthouse.

Founded upon the very same principles raised by attorneys centuries before them, Petitioners and their allies request an order amending the Uniform Trial Court Rules (UTCR) to expressly prohibit civil immigration arrests in and around state courthouses. The petition was filed on December 4, 2018 and is currently pending before the Chief Justice.

The petition responds to growing alarm over the sharp incline of civil immigration arrests in courthouses in Oregon and around the country. The remedy requested reflects similar efforts undertaken by advocates in California, New York, Massachusetts and courts in New Mexico and Washington state to counter to a growing national crisis.[7] This includes a lawsuit filed by the District Attorneys in Suffolk County and Middlesex County, Massachusetts to enjoin federal immigration officials from engaging in courthouse intrusions.

In support of their motion, Petitioners submitted extensive evidence of the disruption caused by civil immigration arrests in courthouses in the state of Oregon. For example:

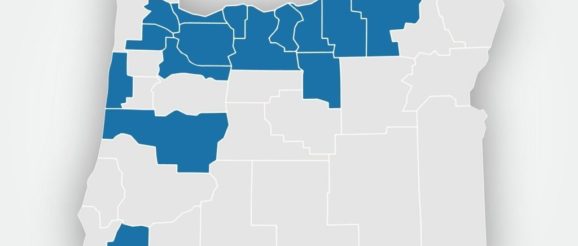

The impact of courthouse intrusions is geographically and demographically broad: planned or executed ICE arrests have occurred, at a minimum, at state courthouses in the Second (Lane), Third (Marion), Fourth (Multnomah), Fifth (Clackamas), Sixth (Umatilla, Morrow), Seventh (Sherman, Gilliam, Wheeler, Wasco, Hood River), Fourteenth (Josephine), Seventeenth (Lincoln), Eighteenth (Clatsop), Twentieth (Washington), and Twenty-fifth (Yamhill) Judicial Districts, and at the municipal courts in Beaverton and Molalla. Those courthouses combined serve nearly 3 million Oregonians—citizen and noncitizen alike.

In a study cited by Petitioners, 83% of surveyed direct services providers reported that their clients had failed to appear in court due to ICE presence in the state courthouse. Moreover, Petitioners report ICE arrests that do not conform with traditional arrest protocols, raising the specter of violations of the Fourth Amendment, the Due Process clause, and anti-discrimination laws. These real-life examples echo the concerns articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court over a century ago, and the unease of current and former judges from around the country today. [8]

A Uniform Trial Court Rule Reflecting an “Ancient” Doctrine

The Petitioners have asked the Chief Justice to issue the following rule:

The proposed rule echoes the common law authority already available to litigants and witnesses under Wemme and prior U.S. Supreme Court authority. Petitioners seek affirmation of this ancient doctrine and its positive application across the state. If Chief Justice Walters issues the rule, it would be effective immediately.

The power of the Oregon courts to govern the fair and equal administration of justice through the issuance of uniform rules is recognized in statute and case law, notably in Smith v. Washington Cty.[9] In Smith, the Oregon Court of Appeals affirmed the ability of the court to engage in weapons searches and other means of securing the safety the courthouse. The court reasoned that, “if courts are to serve as open forums for the resolution of legal conflicts, the participants and the public must feel safe to enter and remain inside.”[10] Similarly here, Petitioners seek the Court’s aid in ensuring the safe participation of all Oregonians in the legal system. They hope that this rule will prevent the racial profiling and harassment of people of color, such as in Mr. Andrade Tafolla’s detention and provide a real, meaningful assurance to all Oregonians that courthouses, like schools, hospitals and churches are special places that are safe for all, no matter their place of birth or color of their skin.

In the meantime, parties and witnesses may use the Wemme and Stewart authority to seek individual writs of protection, now and into the future. However, as Petitioners contend, a patchwork, case-by-case approach gives little consistency across trial courts throughout the state, and may create challenges for litigants and witnesses unfamiliar with complex motions practice. Moreover, the writ offers little protection to a first-time seeker of a judicial remedy where there is no pending matter in which to file.

The Petition submitted to Chief Justice Walters can be found here.

If you, your family, your clients, or your constituents have been affected by ICE intrusions in Oregon courthouses, we would like to hear from you. Comments and questions may be directed to Erin M. Pettigrew, Innovation Law Lab at [email protected].

Press inquiries may be directed to Victoria Bejarano Muirhead, 971-801-6047, [email protected].

[1] Stewart v. Ramsay, 242 US 128, 129, 37 S Ct 44 (1916).

[2] Id.; Brief of Defendant-Appellant, Stewart v. Ramsay, 242 US 128, 129, 37 S Ct 44 (1916). available at: http://moses.law.umn.edu/darrow/documents/Darrow%20brief%20Stewart%20v%20Ramsay.pdf

[3] Stewart, 242 at 129 (1916) (quoting Halsey v. Stewart, 4 NJL 366 (1817) (internal quotation marks omitted)).

[4] Id. at 130 (the word used in the original opinion by the Court was “chary,” a nearly obsolete synonym for “wary” in contemporary English usage).

[5] Id. at 129.

[6] Wemme v. Hurlburt, 133 Or 460, 460, 289 P 372 (1930) (citing Mullen v. Sanborn, 29 A 522 (Md Ct App 1894)). A similar privilege against arrests of subpoenaed witnesses is codified in state statute: ORS 44.090. For a summary of similar cases across the U.S., see Christopher N. Lasch, A Common-Law Privilege to Protect State and Local Courts During the Crimmigration Crisis, 127 Yale L J Forum 410, 431–32 (2017).

[7] Immigrant Defense Project, The Courthouse Trap: How ICE Operations Impacted New York’s Courts in 2018 (January 2019) available at https://www.immigrantdefenseproject.org/wp-content/uploads/TheCourthouseTrap.pdf.; Ctr. Soc. Justice Temple Univ. Beasley Sch. of L., Obstructing Justice: The Chilling Effect of ICE’s Arrests of Immigrants are Pennsylvania’s Courthouses (Jan. 30, 2019) available at https://www2.law.temple.edu/csj/publication/obstructing-justice-the-chilling-effect-of-ices-arrests-of-immigrants-at-pennsylvanias-courthouses/; American Civil Liberties Union, Freezing Out Justice: How Immigration Arrests at Courthouses Are Undermining the Justice System (2018), available at https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/rep18-icecourthouse-combined-rel01.pdf; see also National Immigrant Women’s Advocacy Project, Promoting Access to Justice for Immigrant and Limited English Proficient Crime Victims in an Age of Increased Immigration Enforcement: Initial Report from a 2017 National Survey [hereinafter “NIWAP Report”] (May 3, 2018), available at http://library.niwap.org/wp-content/uploads/Immigrant-Access-to-Justice-National-Report.pdf; Tahirih Justice Center, Key Findings: 2017 Advocate and Legal Service Survey Regarding Immigrant Survivors, available at https://www.tahirih.org/pubs/key-findings-2017-advocate-and-legal-service-survey-regarding-immigrant-survivors/.

California: Application For a Proposed Rule of Court Prohibiting Civil Arrests At California Courthouses, No. 00545059 (Judicial Council of California, August 01, 2018) available at https://www.immigrantdefenseproject.org/wp-content/uploads/Application-to-California-Judicial-Council-for-Proposed-Rule-of-Court-8.1.2018.pdf. ; SB 54, Chapter 495 Law Enforcement: sharing data (2017-2018), approved by Governor Oct. 5, 2017) available at https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB54. ; AB 668, 2019-2020 Reg. Sess. (CA 2019) available at http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB668

New York: S 00425, 2018-2019 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (NY 2019)

Massachusetts: Matter of C. Doe & Others, No. SJ-2019-119, (Supreme Judicial Court for Suffolk County Sep. 18, 2018) available at https://www.masslegalservices.org/system/files/library/Doe-single%20justice%20decision.pdf

King County Superior Court (WA): Court Policy: No Courtroom Arrests Based on Immigration Status, approved by the King County Superior Court Judges on April 22, 2008, available at https://www.ilrc.org/sites/default/files/resources/king_county_courts.pdf.

Bernalillo County Metropolitan Court (NM): Courthouse Access Policy, approved on Sep. 25, 2018, available at https://www.kob.com/kobtvimages/repository/cs/files/Courthouse%20Access%20Policy.pdf

[8] See, e.g., Letter from Thomas A. Balmer, Chief Justice of the State of Oregon, to Jeff Sessions, Attorney General, and John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security (April 6, 2017) available at https://www.opb.org/news/article/oregon-supreme-court-justice-ice-courthouse-letter/; Letter to Acting U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Director (December 12, 2018) available at https://www.scribd.com/document/395488473/Letter-From-Former-Judges-Courthouse-Immigration-Arrests#fullscreen&from_embed

[9] Smith v. Washington Cty., 180 Or App 505, 521 (2002) (construing the phrase “administrative authority and supervision” in ORS 1.002(1)(i)).

[10] Id. at 522.