How an 1800s Midwife Solved a Poisonous Mystery | Innovation| Smithsonian Magazine

The disease was first noted on the Midwestern frontier in the early 1800s as settlers expanded into new territory with their herds. Known initially as “the slows,” “the staggers,” “the trembles” and eventually “milk sickness,” the disease had a terrifying progression. Within days, a formerly healthy person could be bedridden with vomiting, often followed by coma and eventually death. Daniel Drake, a doctor in Cincinnati, described the symptoms as sly and baffling, beginning only with “a general weakness and lassitude, which increase in the most gradual manner.”

It tended to strike in the summer after periods of little rain. It wasn’t present on the East Coast. There was no record of similar illness anywhere else in the world. Settlers were flummoxed—and terrified.

Some blamed spooks and witches. Others, poisonous vapors coming from the earth. People abandoned entire regions, including parts of the Wabash River Valley in Indiana and Illinois, believing them cursed. The State of Kentucky offered $2,000, or nearly $70,000 in today’s money, to anyone who could find the explanation. In DuBois County, the majority of recorded deaths in the early 1800s came from milk sickness. From 1809 to 1927, this strange disease killed thousands of settlers and farmers in the Midwest—including Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

“It’s hard to wrap our heads around how much of a threat it was and how scared people were at the time,” says Luke Manget, a historian of the period and an incoming professor at Western Carolina University.

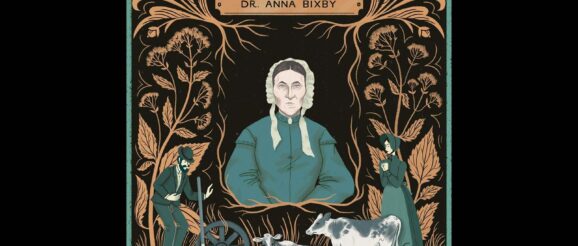

At the time, most frontier families had a milk cow that grazed in the fields and even woodlands near their homes. By the 1820s, the prevailing idea among physicians and settlers was that the illness began with cows consuming some sort of poison, which was then passed to people who consumed contaminated milk or other dairy products. Calves died, as did some adult cows, and some settlers thought cattle were poisoning themselves at wells and springs. But it would be up to a young, quick-witted midwife in Illinois affectionately known as Doctor Anna to solve the puzzle, beginning with the folk observation that she seized upon that would serve as a pivotal clue: Milk sickness was seasonal.

Born in Philadelphia in the early 1800s, Anna Pierce headed west with her family as a young girl. They settled in southern Illinois, in an area called Rock Creek. Around 100 miles east of the Mississippi River, Rock Creek was indeed the American frontier. As a teenager, Anna became “disturbed by the sad state of the health of the pioneers,” according to a 1966 account co-written by William Snively, an Alabama physician, and Louanna Furbee of the American Dental Association. So Anna went to Philadelphia to study nursing, midwifery and dentistry, although historians don’t know where exactly she received her education.

Returning to Rock Creek a few years later as the only medical practitioner in the county, Anna Pierce spent years crisscrossing the region, attending to births and illnesses such as cholera. Likely around this time, she married a man named Isaac Hobbs.

Once milk sickness surfaced in the area, Anna’s family was hit hard. She lost her mother and sister-in-law to the disease. Her father was also debilitated and returned to Philadelphia for treatment. Determined to solve the mystery, she focused on the disease’s seasonal nature and came to believe that plants, rather than water or metals, were the source of the poison. She urged her neighbors to take caution: “I am … telling everyone I can to abstain wholly from milk and butter … till after the killing frosts,” Anna wrote in her journal at the time.

One fall day in 1834, Anna packed a lunch, grabbed her rifle and, accompanied by her dogs, began tracking the cattle through the woods to record what they ate. While she was observing the cows, she ran into an elderly Shawnee woman, who was hiding in the forest to evade her people’s forced migration to Kansas. Touched by her story, Anna gave the woman her lunch and brought her home to rest.

When the woman learned of Anna’s interest in milk sickness, she declared she knew exactly which plant Anna was searching for. Before taking her leave from Anna’s house, she led her host to a nearby ridge and showed her an unassuming plant a few feet high with disc-shaped leaves, a firm stem and a little bundle of small, fuzzy white flowers. It was this delicate forest plant, the woman said, that made cows sick and poisoned their milk.

The plant was Ageratina altissima, or white snakeroot, a small perennial herb native to the eastern half of the United States. Anna began experimenting by feeding white snakeroot to animals, including calves, whom she observed exhibiting the telltale trembling symptoms of milk sickness. She began to spread the word in her community. According to Snively and Furbee’s 1966 article about Anna and her discovery, her campaign quickly began saving lives: On her advice, men in the county went looking through the forests and fields, destroying the plant. Anna also established a garden of white snakeroot in her yard so local residents could learn to identify it. She sent letters inviting physicians to examine the plant, though we don’t know if any responded. Still, after three years, the plant was nearly eradicated in southeastern Illinois.

That should have been the end of a horrible, widespread illness.

It’s not entirely clear why, but it seems word of Anna’s discovery did not spread far. At the time, there were few physicians or established medical journals across the frontier. In addition, authorities were not primed to trust the findings of a frontier midwife. “She was a woman, so no one gave her much thought,” says John Haller, an emeritus professor of history at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale who has written extensively about the history of American medicine.

This article is a selection from the July/August 2023 issue of Smithsonian magazine

Even in 1862, nearly 30 years after her discovery, the disease was still endemic along portions of the Wabash River in Indiana and Illinois. As late as 1885, a North Carolina doctor hypothesized the illness was a result of arsenic poisoning through cows’ milk. In 1965, when the journal Economic Botany compiled a literature review of milk sickness, including period accounts, newspaper articles and academic journals, the authors noted that milk sickness was rarely mentioned even in later 19th-century American medical textbooks. (Such books often neglected frontier medicine.)

By 1900, milk sickness was finally becoming less common, in large part because of the emerging industrialization of agriculture, which standardized safer methods of feeding cows and processing milk. But it wasn’t until 1927—around a half-century after Anna’s death and almost a century after her fateful meeting in the woods—that researchers with the U.S. Department of Agriculture published a chemical analysis on toxic substances in white snakeroot. Anna’s pioneering research into the plant’s toxic properties was not noted in the department’s report.

Indeed, it wasn’t until the mid-1960s that historians and doctors rediscovered her story and began advocating for her recognition. Given the significance of her achievement, Anna arguably deserves a seat alongside Elizabeth Blackwell, Rebecca Lee Crumpler and Susan La Flesche Picotte as one of the most consequential women practicing medicine in the United States in the 19th century. Instead, her name lives on in Southern Illinois largely through a dark, probably apocryphal tale about buried treasure.

Her first husband having died of pneumonia, she went on to marry a man named Eson Bixby, who turned out to be an irredeemable ne’er-do-well. The legend holds that Anna heard a rumor that Eson intended to kill her for her money, so she buried the cash in a cave near the Ohio River. To this day, some believe Anna Bixby’s treasure is still buried in the hills near a village called Cave-in-Rock in Southern Illinois.

Today, of course, most of the milk Americans drink or that is used in dairy products is processed industrially, pooled with that of thousands of other cows to dilute any pathogens or toxins. Modern cows are far more likely to graze in cleared fields, not on the fringes of woodlands, where white snakeroot is most common. The last reported cases of milk sickness in humans were two babies in St. Louis in 1963; though suffering from severe metabolic acidosis, they were treated in a hospital and survived.

Since 1927, biologists have believed that the toxin tremetol, which can be present at relatively high levels in white snakeroot, was the particular substance that caused milk sickness. But it has never been definitively proved, and scientists are still searching for an answer.

And if rural, small-batch dairy farms continue to grow in popularity, Zane Davis, a molecular biologist currently studying white snakeroot at the USDA lab in Logan, Utah, worries the illness might someday return. Davis doesn’t rule out that “it could become a problem in the future”—one that farmers can avoid by learning how to recognize, and root out, this gnarly herb.

The Things They Carried

Physicians in the 19th century had to be ready to treat everything—so they needed a versatile kit

By Ted Scheinman

Dental forceps

Such devices have been around since at least the fourth century B.C., when Aristotle described a tool for oral surgery: “two levers acting in contrary sense having a single fulcrum.” In the U.S., dental forceps gave birth to dental screw forceps, which allowed you to hold a tooth in place while drilling.

Surgical set

Critical items would have included an amputation saw, tourniquet, trephines (for slicing into the skull), bone forceps, a large amputation knife, several smaller knives and suture needles.

Monaural stethoscope

René Laënnec, a French physician and musician, used his flute-carving skills to produce the first stethoscope in 1816. It transformed practitioners’ ability to diagnose chest disorders. Early stethoscopes were simple wood, like this one; the rubber-tubed models we know emerged later in the 19th century.

Lithotomy set

To remove a kidney stone, a physician would insert a slender lithotomy forceps, sometimes with a gorget, through the urethra to crush the stone, then use a scoop to extract the debris.

Medicine chest

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.