A Brief History of the Mason Jar | Innovation | Smithsonian Magazine

As the coronavirus pandemic stretched into spring, then summer, many Americans turned to home gardening. It’s a perfect pandemic hobby—soothing, tactile, a way to get outside when many public spaces are closed. Plus, for the large numbers of people facing unemployment or underemployment, growing food can feel like a bulwark against hunger. By March, when cities began implementing lockdown orders, Google searches for “growing vegetables from scraps” were up 4,650 percent from the previous year. By later in the spring, seed sellers were reporting soaring sales—the venerable W. Atlee Burpee & Co seed company saw its biggest sales season in its 144-year history.

Now, as gardeners find themselves with bumper crops of fruits and veggies, another time-tested hobby is gaining new followers: home canning.

“I have definitely noticed an uptick in canning interest during the pandemic,” says Marisa McClellan, the canning expert behind the website Food in Jars and author of several canning cookbooks. “Traffic is up on my site, I’m getting more canning questions, and there’s a shortage of both mason jars and lids.”

Indeed, stores across America are reporting canning supply backorders that won’t be filled for months.

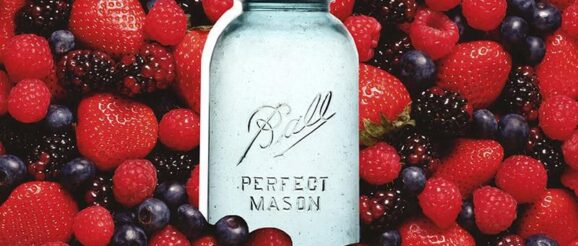

Which brings us to the subject of our story, that American icon, the darling of canners and crafters alike, the mason jar. When you put up a batch of dill pickles or a blackberry compote, you’re using a technology that’s been around for more than 160 years.

It all started with John Landis Mason, a New Jersey-born tinsmith who, in the 1850s, was searching for a way to improve the relatively recent process of home canning. Up until then, home canning involved using wax to create an airtight seal above food. Jars were stoppered with corks, sealed with wax, then boiled. It was messy, and hardly foolproof. Before canning, people in cold climates relied largely on smoking, salting, drying and fermenting to keep themselves fed through winter.

In 1858, a 26-year-old Mason patented threaded screw-top jars “such as are intended to be air and water-tight.” The earliest mason jars were made from transparent aqua glass, and are often referred to by collectors as “Crowleytown Jars,” as many believe they were first produced in the New Jersey village of Crowleytown. Unfortunately for Mason, he neglected to patent the rest of his invention—the rubber ring on the underside of the flat metal lids that is critical to the airtight seal, and made wax unnecessary—until 1868, a full decade later. By this point, mason jars were being manufactured widely. Mason tried to regain control of his invention, but after various court cases and failed business partnerships he was edged out. He died in 1902, allegedly penniless.

Enter the Ball brothers. In 1880, the year after Mason’s original patent expired, the five brothers—Edmund, Frank, George, Lucius and William—bought the small Wooden Jacket Can Company of Buffalo, New York, with a $200 loan from their uncle. The company produced wood-jacketed tin containers for storing things like kerosene, but the Ball brothers soon moved on to tin cans and glass jars. After changing their name to the Ball Brothers Manufacturing Company, they set up shop in Muncie, Indiana, where natural gas fields provided plentiful fuel for glassblowing. Soon they were the largest producer of mason jars in America. Their early jars still bore the words “Mason’s Patent 1858.”

Over the years, Ball and other companies have produced mason jars in a variety of sizes and colors. You can find antique jars in shades of pink, cobalt, aqua, amber and violet. Collectors have paid up to $1,000 for the rare “upside-down” Ball jar, produced between 1900 and 1910 and designed to rest on its lid.

With mason jars readily available in the late 19th century, Americans were able to eat a much wider variety of fruits and vegetables year-round. This brought “great improvement in nutritional health,” writes Alice Ross in The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, first published in 2004. The first dedicated canning cookbook, Canning and Preserving, was published in 1887 by Sarah Tyson Rorer, a food writer and pioneer in the burgeoning field of home economics. Some of Rorer’s recipes—preserved citron, rhubarb jam, chilli vinegar—would be right at home in any contemporary farmer’s market, while others—“mock olives” (made with plums), walnut catsup, peaches stuffed with horseradish and sewn shut with thread—were products of their time. The canning phenomenon even influenced home architecture. So-called “summer kitchens” became increasingly popular as women spent weeks at the end of summer “putting up” fruits and vegetables for winter. The freestanding structures let the main house stay cool during the long canning season.

Home canning had a boom during World War II, when Americans were encouraged to grow “victory gardens” for extra food and propaganda posters featuring mason jars urged women to “Can All You Can.” But it declined in popularity from the late 1940s onward, as food companies leveraged wartime improvements in industrial canning and freezing technology to foist processed foods on the American market. Homemade canned green beans were out, Birds Eye frozen peas were in. The counterculture movement of the 1960s brought another wave of interest in canning, which crested and receeded in the 1970s.

The 21st century has brought a mason jars revival, though not always for their original purpose. The rise of rustic-chic restaurants, barn weddings and farmhouse-style kitchens have seen mason jars used for drinking glasses, flower vases and utensil holders. “Mason jars are still popular because they’re both useful and beautiful,” says McClellan, who works with the Ball brand as a “canning ambassador.” “Whether you use them for canning, dry good storage, drinking glasses, or just to hold pens on your desk, they are functional and pleasing.”

But with the Covid-19 pandemic, mason jars are returning to their original use. Google searches for “canning recipes” and other canning terms are double what they were at this time last year. By fall, many American pantry shelves will be bursting with jars of pickled okra, blackberry jam, tomatillo salsa and peach chutney.

“You see these moments in American history; wherether it’s World War II or the counterculture or the pandemic, canning always comes back,” says Paula Johnson, curator of food history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The museum has more than 1,000 canning jars in its collection, Johnson says. They were donated by a retiring home economics professor from Ohio State University in 1976. The jars come in many sizes and designs, from many different manufacturers, including Ball, Kerr and Atlas.

“[The collection] really does provide a window into home food preservation and the importance of it for so many people,” Johnson says. “This has been something that’s part and parcel of people’s summers for many, many years.”

These days, the Ball Corporation no longer makes its iconic canning jars—they’re actually produced under the name Ball by Newell Brands. In a very 21st century touch, Ball jars have their own Instagram, full of recipes for the modern home canner: tomato bruschetta topping, pineapple-jalapeno relish, caramel apple coffee jam.

John Landis Mason may not have been familiar with the foods. But he certainly would recognize the jars.