Actions, Motivations, and Trust – Innovation Excellence

(Excerpt from my upcoming book The Book of Trust):

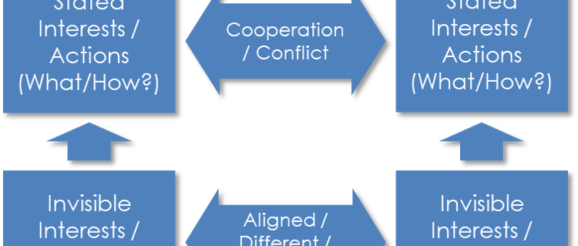

One element of personal shared values is encompassed in the why we are taking action, and what action we choose to take. Imagine two people as in the image below.

Each is driven by motivations and interests that are not necessarily made visible to the other person. These are their “Why”. Why they are doing things. Those can be aligned between the two of them but could also be conflicting (relatively opposite to one another), or simply different (not the same, but not conflicting, either). Those invisible interests or motivations drive them to take action, or state interests publicly. Those actions can be in cooperation with one another or conflicting with one another. How does that affect trust between them? The following table will explain it.

The highest level of trust will result when both people have their “above the fold” interests and actions, but also their motivations aligned. We agree not only what we do and how we do it, but also on why we do it. The second highest level would occur when our stated, public interests and actions are conflicting, but our underlying motivation and values are aligned. This would be when we hold constructive disagreements, where we argue the what and how, but we trust each other due to having aligned why. An interesting phenomenon happens when we agree on what or how we do things, but we don’t agree on why. In other words, we have different motivations for doing the same thing. Even worse, we may have conflicting motivations and values that still lead us to do the same thing. The level of trust would be low, and we will have an ad-hoc dependency on each other. We will work together because we believe we should take the same action, but we recognize that we do it for different, or even opposite reasons. As soon as this action is complete, our “partnership” may fall apart. Faster if it was based on conflicting motivation than on simply different, albeit not conflicting motivation.

If we prefer to take different actions due to different motivations, we almost get to the point in which we don’t care. We will be experiencing a low level of trust, due to the combination of different actions and different motivations. Obviously, the lowest level of trust will be experienced if we not only disagree on the actions to be taken, but we also have conflicting (not just different) motivations.

As you can see from this discussion, the underlying motivation plays a much bigger role in building and maintaining trust than the actions we take. As long as our motivations, our why, are aligned, we can hold a trusted constructive disagreement and make joint decisions. But if our motivations conflict, we will not trust each other. Even if we do agree on what needs to be done and how. It will only be a temporary agreement. Not trust.

But what could happen if we don’t know what the other person’s motivation and values are? The ones not readily visible to others?

If your actions and “above the fold” stated interests are aligned with another person (i.e., you want to achieve the same thing or do something the same way), you might miss the fact that the other person is doing it for a completely different reason, and even worse—for a completely opposite reason than yours. If you don’t know that, you might be caught by surprise the next thing you do something together, or when something changes, and the other person’s “true colors” come to light.

If your actions and “above the fold” stated interest are conflicting with the other person’s (i.e., you want to achieve different/conflicting things or do them in a different/conflicting ways), you might miss the fact that the other person wants to do those things for exactly the same reasons you do, and the focus both of you put on the what and how causes you to lose focus on the why which, in this case, is common to both of you. You will be losing the opportunity to hold a constructive disagreement with someone you can trust because they share your values and motivations, except for the fact that you don’t know about them.

The conclusion is simple: values and motivations are typically hidden. To be able to trust another person you must know theirs, and to be trusted by them, with all the benefits from it, they must know yours.

Image credit: Yoram Solomon

Wait! Before you go…

Choose how you want the latest innovation content delivered to you:

Dr. Yoram Solomon is an inventor, creativity researcher, coach, consultant, and trainer to large companies and employees. His Ph.D. examines why people are more creative in startup companies than in mature ones. Yoram was a professor of Technology and Industry Forecasting at the Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, UT Dallas School of Management; is active in regional innovation and tech transfer; and is a speaker and author on predicting technology future and identifying opportunities for market disruption. Follow @yoram

Dr. Yoram Solomon is an inventor, creativity researcher, coach, consultant, and trainer to large companies and employees. His Ph.D. examines why people are more creative in startup companies than in mature ones. Yoram was a professor of Technology and Industry Forecasting at the Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, UT Dallas School of Management; is active in regional innovation and tech transfer; and is a speaker and author on predicting technology future and identifying opportunities for market disruption. Follow @yoram