An Adaptive-reuse Project Restores a Historic City Landmark and Creates Space for Innovation – retrofit

A Tyson Foods’ redevelopment bridges a family legacy with civic revitalization and historic preservation with modern, sustainable design. Making investments in Springdale, Ark., where the company got its start, family-owned Tyson Foods shows its commitment to “… drive positive change, solve problems, and make the world a little better every day.” One of the company’s investments opened in 2017, reclaiming a 1940s brick building on E. Emma Avenue in downtown Springdale that served as Tyson Foods first headquarters from 1947-69. In addition to rejuvenating a dilapidated site, the Tyson Emma project brought approximately 300 team members to spur growth in the downtown area.

“As designers, we fell in love with the project,” says Eli Hoisington, design principal at HOK’s St. Louis studio, who provided multidiscipline services for the redevelopment. “In the past, agriculture and manufacturing was centered in downtown cores right next to the rail lines. Then Midwest cities and towns suffered because so many people left Main Street. This project is vitally important to Springdale because it brings Tyson back to its roots and spurs the city’s renewal.”

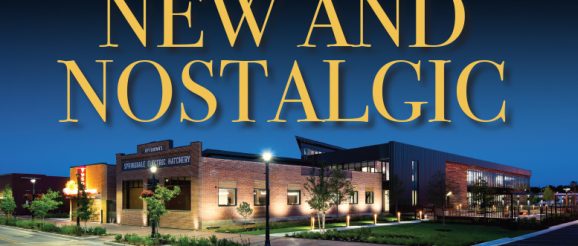

Three original buildings on the site—Tyson Foods’ former headquarters, Jeff D. Brown and Company’s Springdale Electric Hatchery next door and a feed building behind the hatchery—formed the Springdale Poultry Industry Historic District. Although the buildings fell into disrepair, the district was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

The 56,000-square-foot redevelopment reclaims two of the original buildings and incorporates two new ones along with an atrium, creating an interconnected space for Tyson Foods’ Innovation Technology employees.

“The history of the buildings was important to the city and the Tyson family, and we needed to interpret their story through the project’s design,” Hoisington says. “We preserved the site’s heritage and supplemented it with modern additions to create a state-of-the-art workspace that fosters collaboration and creativity.”

RE-FORM AND EVOLVE

Once the project was underway, assessments revealed the feed building’s structure was beyond repair. Despite the fact that it could not be saved, materials found inside the feed building were reclaimed and infused the rest of the development with a special character.

“We deconstructed the building and salvaged a mix of white oak and red oak from the hatchery and feed building’s walls, floors and some of the joists,” says HOK Project Architect Stefanie Hartman. “In addition to knotty pine salvaged from the original headquarters office building, the reclaimed wood accents the interior walls, stair treads and the reception area.”

Hoisington asserts the original wood has a different texture than current building material wood sources. “Older wood tends to come from older-growth trees. The wood grain is tighter and denser than the open- spaced wood available today. It’s beautiful, and brings an entirely different quality to the project,” he notes.

Deconstruction, salvage and repurposing materials is a sustainable use of resources, but Hoisington says saving the two original buildings is the project’s main sustainable feature. “All the embodied energy to make the bricks, mill the wood and create the structure was already there. Retrofitting and adding performance to pre-existing buildings is the most sustainable practice we could implement.”

Because the remaining two buildings were on the National Register, their original exterior walls had to remain intact to maintain their public street presence. The team conducted research—onsite and from drawings—to uncover changes that occurred over the decades. Some original windows were no longer visible, so HOK returned those fenestrations to the headquarters building and hatchery.

Constructed of brick masonry, the headquarters building and the hatchery needed structural reinforcement.

“In particular, the hatchery’s original wood framing had suffered fire, moisture and termite damage over the years and we couldn’t salvage the framing,” Hartman says. “To create a structural support, we inserted a new steel frame inside the brick masonry walls to withstand gravity and lateral loads.”

PHOTOS: Randy Braley, unless otherwise noted

To accommodate hundreds of employees, the addition of new building space was anticipated from the project’s inception. As they examined the site, however, an unusual opportunity presented itself to the architects.

“One of the key things we could take advantage of was the old alley between the headquarters and hatchery,” Hoisington recalls. “We converted the alley into an atrium that straddles the two original buildings and two new ones linking everything together. It’s a special hub that gives people a place to gather.”

The floors of the two original buildings across the alley didn’t align, so stairs in the atrium made of the reclaimed wood help occupants transition from one side of the development to another. The original architecture of the headquarters building steps down on its eastern façade, and the new taller buildings are located on the southern portion of the site. The atrium’s design is “stepped” into two pieces to accommodate the differing building heights and bring visual symmetry to the overall redevelopment.

Inside, the atrium showcases exposed structural steel columns and curtainwall supports, clerestory windows and a ceiling made of new rift-cut white oak veneer with a teak stain.

Drawing on his past experience working with projects listed on the National Register, Hoisington knew the Secretary of the Interior urges designers to clearly delineate between the original and modern elements of historic retrofits. At Tyson Emma, designers set the atrium and the height of the new construction back from the E. Emma Avenue street view to highlight the original buildings’ historic and cultural importance. Intentional use of lighting also differentiates the old and the new.

“We carefully lit the exterior with low lighting in the foreground to celebrate the masonry,” Hoisington explains. “The original buildings are lit from the outside and the new buildings glow from the inside.”

HOK’s lighting team worked with the company’s interior architects to specifically design lighting fixtures and chandeliers inside the building. Interior materials subtly convey an agricultural industry vernacular with walls made of black-finished painted aluminum metal siding, black structural steel square columns, concrete floors, wood and existing masonry.

The buildings include a gallery, meeting space and large gathering space for the Tyson Foods employees. The project is adjacent to the Razorback Greenway shared-use trail and employees are encouraged to enjoy Springdale’s temperate outdoor weather with a bocce ball court, shuffleboard and a fire pit on the west side of the facility.

LEGACY AND CATALYST

Tyson Foods’ investment in downtown inspired others to follow as new developments opened across the street from the facility and restaurants moved into the area.

While the project sparks fresh vitality in the neighborhood, the preserved buildings kindle nostalgia. To signify Tyson Foods’ return to the site, the company recreated its 1940s neon chicken sign for the front of the original office building.

“The restoration resonated with the Tyson family and brought back memories for the people of Springdale,” Hoisington says. “These buildings hadn’t been occupied for a while, and people came by whose parents or grandparents worked in the buildings and recognized it as part of their heritage. It was amazing to watch people in the community see their own story in these buildings, too.”

PHOTOS: Randy Braley, unless otherwise noted

ARCHITECT, INTERIOR DESIGNER, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, STRUCTURAL ENGINEER, SPACE PLANNING AND LIGHTING: HOK

CONCRETE: Diamond Hard from Euclid Chemical