China’s High-Speed Rail: A Case Study in Independent Innovation | Pakistan Defence

Given that innovation of this type is at the center of its new growth model, it is worth examining China’s experience with high-speed rail in a bit of detail.

China’s first high-speed service – from Beijing to Tianjin – started in 2008. By the end of last year, 37,800 km of high-speed rail track have been laid, accounting for just over a quarter of the entire network.

I often choose to take the high-speed train when I travel from Shanghai to Beijing. The 9 AM train takes four and a half hours to reach Beijing’s South railway station. Its average speed along the 1318 km distance – including stops at Nanjing and Jinan – is just over 290 km/hr. At that speed, I can make a late afternoon meeting or an evening event.

My second-class ticket costs around CNY600. This is about half the price of the 9 AM flight, which takes two hours and 20 minutes. The airlines do offer more competitive pricing later in the day, with the 225 PM flight only costing CNY560.

Because of the train’s high speed, it must travel on special tracks, which are designed to be as straight as possible. This makes for a smooth and comfortable ride. The cars are equipped with free Wi-Fi and I can order food to be delivered. This is convenient as the train stops in Jinan at noon.

Train ridership was off last year due to the pandemic. In 2019, close to 2.4 billion trips were made on China’s high-speed trains, up from only 700 million five years earlier.

In its early days, China’s high-speed trains relied heavily on German, French and Japanese prototypes and parts. Over time, domestic inputs have substituted for foreign ones and today an estimated 90 percent of high-speed rail’s supply chain is made in China. Domestic innovations include cars on the Beijing-Harbin line that can withstand very cold temperatures.

China’s high-speed rail project has also led to advances in engineering. For example, the Dali-Ruili Railway Bridge and Gaoligong Mountain Rail Tunnel, are the world’s longest span bridge and Asia’s longest tunnel. And the Badaling Great Wall Station, on the Beijing-Zhangjiakou line, is China’s largest underground.

While Chinese firms have benefitted from the learning-by-doing afforded by the construction of high-speed rail, foreigners have not been shut out. For example, Bombardier Sifang Transportation – a Sino-Canadian joint venture – has supplied hundreds of high-speed rail cars to China State Railway Group and has contracts to maintain the cars following their manufacture.

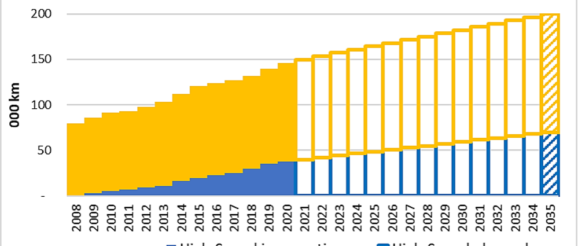

Last August, the China State Railway Group released its plan for developing the rail system over the next 15 years. The national network will comprise 200,000 km of track (up from 146,300 as at the end of last year), of which 70,000 km will be high-speed rail (Figure 1). The goal is to provide a rail link to all cities with populations of 200,000 and a high-speed link for those of 500,000.

While the planned expansion of the rail network should bring a host of benefits, it is not without risk.

A recent report by the World Bank noted that some of China’s heavily used lines – like the one that connects Shanghai and Beijing – generate enough revenue to pay for their operations, maintenance and debt service. However, many lines with low traffic can barely cover their operating and maintenance costs. Moreover, they will be unable to contribute to their debt service costs for many years unless their fares are increased significantly.

If many existing lines are struggling to make ends meet, how will the new lines, which will likely extend to less populated areas fare?

A study just released by MacroPolo, the in-house think tank of the Paulson Institute, provides an assessment of China’s high-speed network as at the end of 2019. It finds that high-speed rail conferred a net benefit of USD378 billion (2.4 percent of GDP) to the economy. It’s annual return on investment is estimated at 6.5 percent.

MacroPolo attributes high-speed rail’s largest benefit, more than 40 percent of the total, to time savings. For distances of 800 km or less, high-speed rail travel is quicker than going by plane. This is because airports are often far from city centers and security checks are time-consuming. This benefit should continue to be important as the network spreads to smaller cities.

Those who are critical of China’s high-speed rail expansion concentrate on loss-making lines and rising debt. These are attributed to ticket prices which are too low to cover the full cost of rail service.

However, transportation is an industry in which market prices do a poor job of balancing true costs and benefits. While traffic jams are the most visible transportation externality, greenhouse gas emissions are even more important. Since no mode of transportation currently prices in its full carbon costs, it is difficult to be sure if ticket prices really are “too low”.

A study by the International Union of Railways concluded that high-speed rail’s carbon footprint can be up to 14 times smaller than car travel and 15 times smaller than travel by plane. These estimates are measured over the full life cycles of planning, construction and operation of the different transport modes.

Given that China is heading toward carbon neutrality by 2060, perhaps a wider rollout of a low-carbon rail system makes sense. In this context, low ticket prices, loss-making rail lines and rising debt are simply the interventions needed to make rail competitive with high-emissions forms of transportation.

High-speed rail, then, is not only a case study in independent innovation, but also a key part of China’s low-carbon future.

China’s High-Speed Rail: A Case Study in Independent Innovation

www.yicaiglobal.com