Climate change: COP26 Glasgow will provide world stage for Scotland’s green innovation

Every year since 1994, the UN has gathered together the world’s governments at its Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) conference of the parties (COP), held in a different country each time. The convention’s ultimate aim is to prevent “dangerous” human interference with the climate system. The onus is on developed countries to lead the way and the convention directs funds to developing countries to help them in their efforts.

COP25, held in Madrid at the beginning of December 2019, did not end well. Swedish youth activist Greta Thunberg’s solemn speech gave short shrift to countries neglecting their responsibilities, and the likes of the US President, Donald Trump, and Brazil’s President, Jair Bolsonaro, responded with personal attacks.

Tensions ran high when climate justice activists were barred from entering the venue and talks stalled, and negotiations ending two days late with a compromise deal on cutting global carbon emissions. Given the raised status of the world’s climate emergency, it was a disappointing end to a conference for which many had high hopes.

In the cold light of a new year, everyone from activists to world leaders are reflecting on COP25’s ultimate failure to set down rules on creating a carbon market between countries. But already, behind the scenes, the UK is looking to the next summit – because this year COP26 will be pitching its tent in Glasgow.

More than 30,000 people are expected to descend on the city in November 2020. For those who live and work in Glasgow it will be a chance to experience being part of an important climate action event. People from around the country will be able to participate in hundreds of events that will be happening across the city. So why will COP26 be such a big occasion for Glasgow, and what will the city itself bring to the mix?

Why hosting COP26 is a big deal

The world’s governments have met every year for nearly three decades to (try to) agree how to stop – or at least reduce the impacts of – climate change. But the fact that these nations have not been able to meet the overall UNFCCC objectives is one of the reasons we now face a global climate emergency.

As world summits go, they don’t get much more important than the UN’s climate change convention. In those three decades, this will be the first time a COP summit has been held in the UK. From a policy perspective, COP26 will be important for at least four reasons:

1. It will take place in the year when all countries are asked to submit their new long-term goals – so ambition to address the global climate emergency will be high on the agenda.

2. It will have to finish the work that COP25 was unable able to conclude – setting out the rules for a carbon market between countries.

3. From Glasgow onwards, the implementation of the 2015 Paris Agreement will be the key driver of international climate action.

4. COP26 will come just weeks after the US presidential election with the potential implications this will have for US climate policy and US participation in COP26.

Come November 2020, the eyes of the world will be firmly on Glasgow.

Glasgow on show

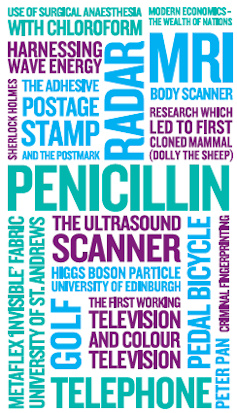

Scotland has a long and rich history of discovery and innovation, including Glasgow’s past as a world-class centre of shipbuilding, trade and industrial production – a legacy that has contributed to greenhouse gas emissions but has also added much to the quality of human life. From pioneering work on the steam engine and wind turbines, to the invention of and the life-saving discoveries of penicillin, gin and tonic and Billy Connolly’s shipyard humour, Glasgow has helped shape the modern world.

Glasgow and its history can also shed light on how cities, societies and people can reinvent themselves from a former industrial workhorse to a city of culture, services and new green technologies. Scotland’s collective commitment to net-zero emissions of all greenhouse gases by 2045 now puts the country at the forefront of real action on the climate emergency. During COP26, Glasgow’s research and innovation will be on show to the world.

Engineers are leading the development of renewable technologies such as tidal energy and floating offshore wind turbines. Scotland is at the forefront of establishing hydrogen as a viable energy source, providing hubs for related skills and knowledge-sharing, to ensure that new technologies can be integrated into the grid and controlled.

Scotland also leads the way not only on the science innovation, but on ways in which research and development can provide community-informed solutions to sea and climate change challenges, and on how climate change relates to Scotland’s coastline and .

Researchers in Scotland are also at the forefront of the science-policy-practice interface, working with people in the field to deliver climate change risk and adaptation policies. And with climate change already a reality, Glasgow is also producing science that helps communities become more prepared and resilient.

Shutterstock

Glasgow’s experts and innovators will have their moment to shine at COP26 – a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to connect with those deciding the direction and effectiveness of the global debate on climate change action. COP26 Glasgow can also be an inspirational event for Scotland’s young people, the generation which will inherit both the burden of climate change and the means to address it.

As we build up to COP26, the Scottish government and Glasgow City Council, alongside the universities of Strathclyde, Glasgow and Glasgow Caledonian, will be planning numerous events that will run alongside the main COP26 activities.

The countdown has begun. Glasgow will seek to demonstrate to the world how Scottish research and innovation is playing an important role in tackling the global climate emergency.

Christopher White receives funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the Low Carbon Power and Energy Program, various Australian/Tasmanian State Government research funding programs, and the Bushfire and Natural Hazard CRC.

Vicky Coy (Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult) and Larissa Naylor (School of Geographical & Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow) contributed to the writing of this article.

Francesco Sindico has received funding from the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the British Academy, the UKRI Global Challenges Research Fund and Scottish Government.

Keith Bell receives funding from the UKRI, Climate XChange, Scottish Power, SSE, Wood Group and National Grid ESO. He is affiliated with the University of Strathclyde and the UK Energy Research Centre. He is a member of the Committee on Climate Change but has contributed to this article in a personal capacity.