Competing in Time: How DoD Is Losing The Innovation Race To China

If the new DOD task force on China is serious about looking at the state of our technology competition, it needs to understand that the balance of technological power has shifted – and it has primarily been a self-inflicted wound. The best ideas no longer arise in a US defense industry encumbered by 60 years of Stalinist-style central planning and security controls, but from commercial sources that once were primarily in the U.S. and are now globalized.

Bill Greenwalt

What is most important is that, in these private industries, time-based innovation, experimentation, and operational prototyping are the coin of the realm. For better or worse, the way the U.S. military innovated in the 1950s, before well-intended “reforms” stifled creativity and risk-taking, is now the dominant model for commercial innovators worldwide, including in adversary nations. To make matters worse, the current U.S. defense innovation model’s lack of value and disregard for time now keep some of the best firms and engineers from working on defense solutions.

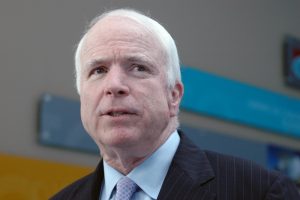

We’ve tried to fix this problem – with very limited success. Five years ago, Senator John McCain, then Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, came to the conclusion that the U.S. was not only losing its technological edge, but was at risk of falling behind in the military competition with its adversaries. He intuitively understood that there was a need to go faster and that startups like SpaceX were innovating the way the U.S. government once did during the Space Race. The result of these concerns was the enactment into law of a series of new authorities to streamline or outright bypass the rigidly linear and centrally planned budget, contracting, acquisition, and requirements processes. These changes were designed to allow the military services and defense agencies a pathway around the existing system to once again focus on speedy development and deployment.

A return to a focus on time and urgency was designed to be the new driving factor in defense innovation. This would allow the U.S. to go back to an era of experimentation, rapid operational prototyping, and the placing of multiple competing technological bets all designed to get capability in the hands of the warfighter in less than five years. The McCain reforms were based on historical data and case examples of what the U.S. was once able to achieve in World War II and at the height of the Cold War. A new report issued by the Hudson Institute on Competing in Time mines this data and compares the time it has taken DOD and the commercial sector to bring innovation to market since World War II. This report, which I co-wrote with Dan Patt, outlines the enormity of the time-based innovation problem the U.S. now faces in our competition with China.

Click to read the full report from AEI and the Hudson Institute.

The results are not inspiring. Five years later, despite McCain’s efforts, we may have already lost the next arms race and have no clear path to regain the initiative. There have been a few pockets of excellence in the Air Force, the Defense Innovation Unit, and various defense innovation cells that have tried to take advantage of the new acquisition flexibilities such as Section 804 Mid-Tier Acquisition and expanded Other Transactions authorities. However, unimaginative implementation and even outright sabotage by the central planning apparatchiks in DoD and congressional staff bureaucracies have undermined these reforms.

This is not being done out of malice or support for the Chinese communist party, but because the current staff and civil servants who advise members of Congress and political appointees are victims of a seven-decades-old ideology and management approach. This approach, now deeply engrained in defense management culture, process, law, and regulation, is based on the concepts of scientific management that were once fashionable in the Soviet Union and at the vanguard of the 1950s U.S. auto industry before it was outcompeted by Japan in the 1970s. Centralized, predictive program budgeting, management, and oversight were then thought to be superior to the trial and error and messiness of time-constrained, decentralized experimentation and the seemingly wastefulness of having multiple sources rapidly prototyping potential solutions.

The post-Sputnik DOD management system instead resulted in stifling innovation. For over 60 years since the adoption of central planning in the 1958 Defense Reorganization Act that ushered in the systems analysis age and the establishment of PPBS in 1961, the U.S. has seen its defense innovation system evolve to a point where it takes 15 years to deliver marginal incremental capability improvements to existing systems. It now takes seven years in decision time just to start work on a new program; to deliver anything remotely novel can take, as it did with the F-35, 21 additional years to get to Initial Operational Capability. Time is an afterthought as process, compliance and a false confidence in long-range predictions drives decision making in the Pentagon, Congress, and the defense industry.

Sen. John McCain

New political appointees, members of Congress, and the current military leadership need to understand that the levers of the current PPBE, 5000, JCIDs and FAR processes can’t be turned by far-seeing planners and out will pop new innovation in a predictive manner. The best that these processes can provide are very marginal changes to exiting capabilities by the year 2035, but more than likely not until 2040. That is far too late to be competitive, as by this time the Chinese taking advantage of commercial innovation and practices will have had the benefit of 4 or more potentially disruptive innovation turns that can result in menacing new deployed capabilities.

While McCain was once on to something by trying to make changes at the margin to allow segments of innovation to bloom, what is now required is an even more radical overhaul of the entire defense management system. Time is of the essence.