Does lunch have to be 45 minutes? Rethinking school schedules to support innovation

Editor’s note: This story led off this week’s Future of Learning newsletter, which is delivered free to subscribers’ inboxes every Wednesday with trends and top stories about education innovation.

Why do most middle schools have seven or eight periods of 45 to 60 minutes each? Why does lunch tend to last 45 minutes? In many places, it’s simply tradition.

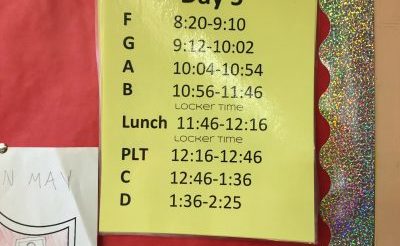

Furman Brown, CEO and co-founder of Tegy (as in stra-tegy), is trying to get schools to rethink basic assumptions about scheduling, and in so doing, position themselves for more comprehensive educational innovations. Brown helps schools design schedules where classes end at different times and last different lengths, where midday lunch and enrichment classes give teachers in core content areas up to 100 minutes of collaboration time per day, and where team teaching can get student-to-teacher ratios as low as 10-to-one without hiring any new staff members.

Many schools want to incorporate more innovative teaching and learning methods in their schools. But scheduling isn’t a particularly common target for redesign – much to Brown’s frustration.

“It affects every moment of a teacher and learner’s educational experience, yet we don’t think about it as a thing to leverage,” he said.

One of Brown’s current projects is helping groups of elementary and middle schools in Colorado and New Jersey reconsider their school days. The work is funded by Fremont Street, a Boston-based philanthropic fund founded in 2017 to focus on supporting small- and medium-sized districts in mostly suburban and rural communities – places that don’t already get a lot of outside funding and attention for education innovation.

Letting these schools focus on time first was a strategic move on the part of Fremont Street, according to Ben Kutylo, the fund’s co-founder and president. Once educators manage to create more time for targeted student supports or teacher collaboration, the logical next step is figuring out how to best use that time.

“They naturally start to move toward thinking about new instructional strategies,” Kutylo said.

So far, he says, that’s what’s happening. Schools are using their new schedules to fit in more teacher collaboration that leads to better experiences for kids, they’re offering teachers more opportunities to observe what their colleagues are trying in the classroom, they’re adding interventions to ensure students get the supports they need, and they’re being more creative and inclusive about the ways they serve special education students because of lower class sizes.

Importantly, focusing on schedules stays away from the baggage certain fads like personalized learning have acquired. Some teachers don’t want their schools to adopt personalized learning initiatives if it means overhauling their teaching strategies without the time and support to do it well. But Kutylo has found that newfound flexibility in the school day can lay the groundwork for more support of personalized learning.

The Unlocking Time Project, run by education software company Abl and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (which is among The Hechinger Report’s many funders), has similar goals. Schools nationwide can go to Unlockingtime.org and find free resources to help them rethink their school schedules. There’s a survey offering school leaders a way to gather feedback about how to better use time, as well as an explainer about nine common bell schedules and examples of 17 strategies schools can tackle during the time they have. These strategies include adding a regular flex-time period to offer students more control over their learning, incorporating online learning elements into the school day, creating weeklong interdisciplinary project sessions that cross class periods and bringing more small-group instruction into the school day.

Unlocking Time launched last July and Abl has been collecting data from participating schools to produce a report later this year about how schools typically use time, how some are innovating with time and why time should be at the center of a deeper national conversation.

These resources focus on master scheduling. Tegy, by contrast, takes a step back to focus on organizational design, pushing schools to question their assumptions about learning and staffing before considering changes to the school schedule.

One key shift Brown encourages is having schools separate the schedules of teachers and students. Everyone doesn’t need the same size blocks of time for classes and lunch. That shift, Brown says, tends to open up a range of other opportunities.

Schools vary, though, in how much they take advantage of.

“A lot of schools don’t do things that are radically different,” Brown said. “They tweak in key ways.”

Some do attempt major changes. But the beauty of reconsidering time is that every school can approach it in a way that fits that school. And even small changes can be powerful.

This story about school schedules was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our newsletters.

The post Does lunch have to be 45 minutes? Rethinking school schedules to support innovation appeared first on The Hechinger Report.