Evolving Adult ADHD Care: Preparatory Evaluation of a Prototype Digital Service Model Innovation for ADHD Care

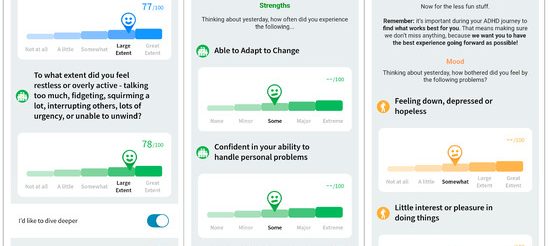

Evolving Adult ADHD Care: Preparatory Evaluation of a Prototype Digital Service Model Innovation for ADHD Care 1 2 3 4 5 6 * Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024 , 21 (5), 582; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21050582 (registering DOI) Abstract : 1. Introduction 1.1. The Prototype Service Innovation 1.2. Research Aims and Objectives (1) Identifying barriers and enablers for ADHD health service innovation; (2) Understanding how this digital intervention can impact the clinical experience, and; (3) Assessing the acceptability of individual features of the prototype ADHD service innovation in enhancing ADHD management. 2. Materials and Methods (1) The characteristics of the digital ADHD care service innovation, including factors such as evidence strength and quality, and the usability and customisability of the app. (2) The outer setting, which in this study encompasses ADHD treatment needs and resources. (3) The characteristics of the potential participants of this innovation, such as their knowledge and attitudes. Multiple Readings: Working independently to start, researchers read the text several times to become familiar with it and reflect on its content. Identify Meaning Units: Within the text, segments were identified that described a phenomenon. These were the meaning units. Assign codes: The essential content from the meaning units was highlighted and assigned relevant codes, illustrating the themes that they represented. Theme Comparison: Researchers compared codes based on similarities and differences and organized them into themes. These themes covered various aspects, including barriers or enablers of the service innovation, interaction concerns, and visual design issues (such as clarity and ease of use). Sampling 3. Results 3.1. Consumer Discussion Themes 3.1.1. Contextual Barriers to Better ADHD Care Identified by Consumers – Ignorance and Prejudice – Trust – Impatience 3.1.2. Potential Enablers of the ADHD Service Innovation Identified by ADHD Care Consumers – Validation/Empowerment – Privacy and Data Security – Tailoring – Access 3.2. Health Professionals’ Discussion Themes 3.2.1. Contextual Barriers to Better ADHD Care Identified by Health Professionals – Complexity – Sustainability 3.2.2. Potential Enablers of the ADHD Service Innovation Identified by Health Professionals – Transparent Privacy and Security Frameworks – Streamlining – Connected Care – Wishlist/Need for Tailoring Recommended Social and Lifestyle Metrics To comprehensively manage and support individuals with ADHD, several clinicians recommended that the app be expanded to embrace a holistic approach that delves deep into various facets of their lives. 4. Discussion 4.1. CFIR Construct: Outer Setting Implications for the Desired Service Innovation Based upon the Outer Setting 4.2. CFIR Construct: Participant Characteristics Implications for the Desired Service Innovation Based upon ADHD Practitioner Characteristics 4.3. Service Innovation Characteristics Implications for the Desired Service Innovation Based upon the Prototype Design 5. Limitations 6. Conclusions Author Contributions Funding Institutional Review Board Statement Informed Consent Statement Data Availability Statement Conflicts of Interest References Song, P.; Zha, M.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Rudan, I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2021 , 11, 04009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] DSMTF American Psychiatric Association; American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] Asherson, P.; Akehurst, R.; Kooij, J.S.; Huss, M.; Beusterien, K.; Sasané, R.; Gholizadeh, S.; Hodgkins, P. Under Diagnosis of Adult ADHD: Cultural Influences and Societal Burden. J. Atten. Disord. 2012 , 16, 20S–38S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Ogrodnik, M.; Karsan, S.; Heisz, J.J. Mental Health in Adults With ADHD: Examining the Relationship With Cardiorespiratory Fitness. J. Atten. Disord. 2023 , 27, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Abdelnour, E.; Jansen, M.O.; Gold, J.A. ADHD Diagnostic Trends: Increased Recognition or Overdiagnosis? Mo. Med. 2022 , 119, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] Hinshaw, S.P.; Scheffler, R.M. ADHD in the Twenty-First Century. Oxf. Textb. Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2018 , 9. [Google Scholar] Núñez-Jaramillo, L.; Herrera-Solís, A.; Herrera-Morales, W.V. ADHD: Reviewing the Causes and Evaluating Solutions. J. Pers. Med. 2021 , 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Xu, G.; Strathearn, L.; Liu, B.; Yang, B.; Bao, W. Twenty-Year Trends in Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder among US Children and Adolescents, 1997-2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2018 , 1, e181471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Zalsman, G.; Shilton, T. Adult ADHD: A New Disease? Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2016 , 20, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Faraone, S.V.; Spencer, T.J.; Montano, C.B.; Biederman, J. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults: A Survey of Current Practice in Psychiatry and Primary Care. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004 , 164, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Kooij, S.J.; Bejerot, S.; Blackwell, A.; Caci, H.; Casas-Brugué, M.; Carpentier, P.J.; Edvinsson, D.; Fayyad, J.; Foeken, K.; Fitzgerald, M. European Consensus Statement on Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD. BMC Psychiatry 2010 , 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] McCarthy, S.; Asherson, P.; Coghill, D.; Hollis, C.; Murray, M.; Potts, L.; Sayal, K.; de Soysa, R.; Taylor, E.; Williams, T. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Treatment Discontinuation in Adolescents and Young Adults. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009 , 194, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Rivas-Vazquez, R.A.; Diaz, S.G.; Visser, M.M.; Rivas-Vazquez, A.A. Adult ADHD: Underdiagnosis of a Treatable Condition. J. Health Serv. Psychol. 2023 , 49, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Chrysanthos, N. Senate Inquiry: Dissenting Doctors Warn That ADHD Is Overdiagnosed and Overmedicated in Australian Children and Adults. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/adhd-overdiagnosed-and-overmedicated-say-dissenting-doctors-20231018-p5ed50.html (accessed on 17 November 2023). Coghill, D. A Senate Inquiry Says Australia Needs a National ADHD Framework to Improve Diagnosis and Reduce Costs. The Conversation. 2023. Available online: http://theconversation.com/a-senate-inquiry-says-australia-needs-a-national-adhd-framework-to-improve-diagnosis-and-reduce-costs-215798 (accessed on 17 November 2023). Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra. Assessment and Support Services for People with ADHD. 2023. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/ADHD/Report (accessed on 17 November 2023). Ginsberg, Y.; Quintero, J.; Anand, E.; Casillas, M.; Upadhyaya, H.P. Underdiagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Adult Patients: A Review of the Literature. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014 , 16, 23591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Rasmussen, K.; Levander, S. Untreated ADHD in Adults: Are There Sex Differences in Symptoms, Comorbidity, and Impairment? J. Atten. Disord. 2009 , 12, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Bisset, M.; Brown, L.E.; Bhide, S.; Patel, P.; Zendarski, N.; Coghill, D.; Payne, L.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Middeldorp, C.M.; Sciberras, E. Practitioner Review: It’s Time to Bridge the Gap–Understanding the Unmet Needs of Consumers with Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder–a Systematic Review and Recommendations. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023 , 64, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Cheung, C.H.; Rijdijk, F.; McLoughlin, G.; Faraone, S.V.; Asherson, P.; Kuntsi, J. Childhood Predictors of Adolescent and Young Adult Outcome in ADHD. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015 , 62, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Fridman, M.; Banaschewski, T.; Sikirica, V.; Quintero, J.; Erder, M.H.; Chen, K.S. Factors Associated with Caregiver Burden among Pharmacotherapy-Treated Children/Adolescents with ADHD in the Caregiver Perspective on Pediatric ADHD Survey in Europe. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017 , 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Shafik, S.A.; othman El-Afandy, A.M.; Allam, S.N.B. Needs and Health Problems of Family CareGivers and Their Children with Attention Deficit Hyperacivity Disorder. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2023 , 10, 7–23. [Google Scholar] Krinzinger, H.; Hall, C.L.; Groom, M.J.; Ansari, M.T.; Banaschewski, T.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Carucci, S.; Coghill, D.; Danckaerts, M.; Dittmann, R.W. Neurological and Psychiatric Adverse Effects of Long-Term Methylphenidate Treatment in ADHD: A Map of the Current Evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019 , 107, 945–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Lavoipierre, A. How an ADHD Diagnosis was the Start of Natalia’s Life Unravelling—ABC Listen. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/backgroundbriefing/how-an-adhd-diagnosis-was-the-start-of-natalia-s-life-unravellin/103115166 (accessed on 17 November 2023). Jensen, P.S.; Arnold, L.E.; Swanson, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Abikoff, H.B.; Greenhill, L.L.; Hechtman, L.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Pelham, W.E.; Wells, K.C. 3-Year Follow-up of the NIMH MTA Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007 , 46, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Moriyama, T.S.; Polanczyk, G.V.; Terzi, F.S.; Faria, K.M.; Rohde, L.A. Psychopharmacology and Psychotherapy for the Treatment of Adults with ADHD—a Systematic Review of Available Meta-Analyses. CNS Spectr. 2013 , 18, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] The Social and Economic Costs of ADHD in Australia | Deloitte Australia | Deloitte Access Economics, Healthcare, Economics. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/au/en/services/economics/perspectives/social-economic-costs-adhd-Australia.html (accessed on 13 December 2023). Badesha, K.; Wilde, S.; Dawson, D.L. Mental Health Mobile App Use to Manage Psychological Difficulties: An Umbrella Review. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2022 , 27, 241–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Fichten, C.S.; Havel, A.; Jorgensen, M.; Wileman, S.; Harvison, M.; Arcuri, R.; Ruffolo, O. What Apps Do Postsecondary Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Actually Find Helpful for Doing Schoolwork? An Empirical Study. J. Educ. Learn. 2022 , 11, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Knouse, L.E.; Hu, X.; Sachs, G.; Isaacs, S. Usability and Feasibility of a Cognitive-Behavioral Mobile App for ADHD in Adults. PLOS Digit. Health 2022 , 1, e0000083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Lakes, K.D.; Cibrian, F.L.; Schuck, S.E.; Nelson, M.; Hayes, G.R. Digital Health Interventions for Youth with ADHD: A Mapping Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022 , 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Moëll, B.; Kollberg, L.; Nasri, B.; Lindefors, N.; Kaldo, V. Living SMART—A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Guided Online Course Teaching Adults with ADHD or Sub-Clinical ADHD to Use Smartphones to Structure Their Everyday Life. Internet Interv. 2015 , 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Lattie, E.G.; Stiles-Shields, C.; Graham, A.K. An overview of and recommendations for more accessible digital mental health services. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022 , 1, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Kawamoto, K.; Houlihan, C.A.; Balas, E.A.; Lobach, D.F. Improving Clinical Practice Using Clinical Decision Support Systems: A Systematic Review of Trials to Identify Features Critical to Success. Bmj 2005 , 330, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Păsărelu, C.R.; Andersson, G.; Dobrean, A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder mobile apps: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2020 , 138, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Akbar, S.; Chen, J.A.; Laranjo, L.; Lau, A.Y.S.; Coiera, E.; Magrabi, F. Safety concerns with consumer-facing mobile health applications and their consequences. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–7 November 2018. [Google Scholar] Powell, L.; Parker, J.; Robertson, N.; Harpin, V. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Is there an APP for that? suitability assessment of Apps for children and young people with ADHD. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017 , 5, e7371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Seery, C.; Wrigley, M.; O’Riordan, F.; Kilbride, K.; Bramham, J. What adults with ADHD want to know: A Delphi consensus study on the psychoeducational needs of experts by experience. Health Expect. 2022 , 25, 2593–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Selaskowski, B.; Steffens, M.; Schulze, M.; Lingen, M.; Aslan, B.; Rosen, H.; Kannen, K.; Wiebe, A.; Wallbaum, T.; Boll, S. Smartphone-assisted psychoeducation in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2022 , 317, 114802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Selaskowski, B.; Reiland, M.; Schulze, M.; Aslan, B.; Kannen, K.; Wiebe, A.; Wallbaum, T.; Boll, S.; Lux, S.; Philipsen, A. Chatbot-supported psychoeducation in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Randomised controlled trial. BJPsych Open 2023 , 9, e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Tsirmpas, C.; Nikolakopoulou, M.; Kaplow, S.; Andrikopoulos, D.; Fatouros, P.; Kontoangelos, K.; Papageorgiou, C. A Digital Mental Health Support Program for Depression and Anxiety in Populations with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Feasibility and Usability Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023 , 7, e48362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Surman, C.; Boland, H.; Kaufman, D.; DiSalvo, M. Personalized remote mobile surveys of adult ADHD symptoms and function: A pilot study of usability and utility for pharmacology monitoring. J. Atten. Disord. 2022 , 26, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] García-Magariño, I.; Bedia, M.G.; Palacios-Navarro, G. FAMAP: A Framework for Developing m-Health Apps; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 850–859. [Google Scholar] Shaw, J.; Agarwal, P.; Desveaux, L.; Palma, D.C.; Stamenova, V.; Jamieson, T.; Yang, R.; Bhatia, R.S.; Bhattacharyya, O. Beyond “implementation”: Digital health innovation and service design. NPJ Digit. Med. 2018 , 1, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Bertagnoli, A. Digital mental health: Challenges in Implementation. In Proceedings of the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting, New York, NY, USA, 6–8 May 2018. [Google Scholar] Borghouts, J.; Eikey, E.; Mark, G.; De Leon, C.; Schueller, S.M.; Schneider, M.; Stadnick, N.; Zheng, K.; Mukamel, D.; Sorkin, D.H. Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with digital mental health interventions: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021 , 23, e24387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Gilbody, S.; Littlewood, E.; Hewitt, C.; Brierley, G.; Tharmanathan, P.; Araya, R.; Barkham, M.; Bower, P.; Cooper, C.; Gask, L. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): Large scale pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015 , 2015, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Jacob, C.; Sanchez-Vazquez, A.; Ivory, C. Social, organizational, and technological factors impacting clinicians’ adoption of mobile health tools: Systematic literature review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020 , 8, e15935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004 , 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Barrett, M.; Davidson, E.; Prabhu, J.; Vargo, S.L. Service innovation in the digital age. MIS Q. 2015 , 39, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Dai, Y.; Yu, Y.; Dong, X.-Y. mHealth Applications Enabled Patient-oriented Healthcare Service Innovation. In Proceedings of the PACIS 2020 Proceedings, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 22–24 June 2020. [Google Scholar] Moullin, J.C.; Dickson, K.S.; Stadnick, N.A.; Rabin, B.; Aarons, G.A. Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement. Sci. 2019 , 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008 , 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Stone, A.A.; Shiffman, S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavorial medicine. Ann. Behav. Med. 1994 , 16, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Bidargaddi, N.; Schrader, G.; Klasnja, P.; Licinio, J.; Murphy, S. Designing m-Health interventions for precision mental health support. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020 , 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Fossey, E.; Harvey, C.; McDermott, F.; Davidson, L. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2002 , 36, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Vandekerckhove, P.; De Mul, M.A.; Bramer, W.M.; De Bont, A.A. Generative participatory design methodology to develop electronic health interventions: Systematic literature review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020 , 22, e13780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022 , 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] van Kessel, R.; Roman-Urrestarazu, A.; Anderson, M.; Kyriopoulos, I.; Field, S.; Monti, G.; Reed, S.D.; Pavlova, M.; Wharton, G.; Mossialos, E. Mapping factors that affect the uptake of digital therapeutics within health systems: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023 , 25, e48000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006 , 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022 , 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Choi, W.-S.; Woo, Y.S.; Wang, S.-M.; Lim, H.K.; Bahk, W.-M. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in adult ADHD compared with non-ADHD populations: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 2022 , 17, e0277175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Newcorn, J.H.; Weiss, M.; Stein, M.A. The complexity of ADHD: Diagnosis and treatment of the adult patient with comorbidities. CNS Spectr. 2007 , 12, 1–14, quiz 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Barbaresi, W.J.; Campbell, L.; Diekroger, E.A.; Froehlich, T.E.; Liu, Y.H.; O’Malley, E.; Pelham, W.E., Jr.; Power, T.J.; Zinner, S.H.; Chan, E. Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics clinical practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with complex attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2020 , 41, S35–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Wolraich, M.L.; Hagan, J.F.; Allan, C.; Chan, E.; Davison, D.; Earls, M.; Evans, S.W.; Flinn, S.K.; Froehlich, T.; Frost, J. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2019 , 144, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Arean, P.A.; Hallgren, K.A.; Jordan, J.T.; Gazzaley, A.; Atkins, D.C.; Heagerty, P.J.; Anguera, J.A. The use and effectiveness of mobile apps for depression: Results from a fully remote clinical trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016 , 18, e330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Carlbring, P.; Maurin, L.; Törngren, C.; Linna, E.; Eriksson, T.; Sparthan, E.; Strååt, M.; von Hage, C.M.; Bergman-Nordgren, L.; Andersson, G. Individually-tailored, Internet-based treatment for anxiety disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011 , 49, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Engdahl, P.; Svedberg, P.; Lexén, A.; Tjörnstrand, C.; Strid, C.; Bejerholm, U. Co-design Process of a Digital Return-to-Work Solution for People with Common Mental Disorders: Stakeholder Perception Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023 , 7, e39422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Roepke, A.M.; Jaffee, S.R.; Riffle, O.M.; McGonigal, J.; Broome, R.; Maxwell, B. Randomized controlled trial of SuperBetter, a smartphone-based/internet-based self-help tool to reduce depressive symptoms. Games Health J. 2015 , 4, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Srivastava, S.C.; Shainesh, G. Bridging the service divide through digitally enabled service innovations. Mis Q. 2015 , 39, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Alsadah, A.; van Merode, T.; Alshammari, R.; Kleijnen, J. A systematic literature review looking for the definition of treatment burden. Heliyon 2020 , 6, e03641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Orji, R.; Lomotey, R.; Oyibo, K.; Orji, F.; Blustein, J.; Shahid, S. Tracking feels oppressive and ‘punishy’: Exploring the costs and benefits of self-monitoring for health and wellness. Digit. Health 2018 , 4, 2055207618797554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Alshehhi, Y.A.; Abdelrazek, M.; Philip, B.; Bonti, A. Understanding user perspectives on data visualisation in mHealth apps: A survey study. IEEE Access 2023 , 11, 84200–84213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Aryana, B.; Brewster, L. Design for mobile mental health: Exploring the informed participation approach. Health Inform. J. 2020 , 26, 1208–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Su, J.; Shen, K.N.; Guo, X. Building an Empowerment Cycle for Value Co-creation in mHealth Services. In Proceedings of the PACIS 2021 Proceedings 2021, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 12–14 July 2021; Volume 206. [Google Scholar] Rapp, A.; Cena, F. Self-Monitoring and Technology: Challenges and Open Issues in Personal Informatics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 613–622. [Google Scholar] Alqahtani, F.; Orji, R. Insights from user reviews to improve mental health apps. Health Inform. J. 2020 , 26, 2042–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] Jang, S.; Kim, J.-J.; Kim, S.-J.; Hong, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, E. Mobile app-based chatbot to deliver cognitive b ehavioral therapy and psychoeducation for adults with attention deficit: A development and feasibility/usability study. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2021 , 150, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Bussing, R.; Koro-Ljungberg, M.; Gurnani, T.; Garvan, C.W.; Mason, D.; Noguchi, K.; Albarracin, D. Willingness to use ADHD self-management: Mixed methods study of perceptions by adolescents and parents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016 , 25, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] Figure 1. Example prototype mobile self-monitoring questionnaires shared with research participants during research interviews. Reproduced with permission from goAct Pty. Ltd. Figure 2. Example prototype mobile self-monitoring symptom checker questionnaires shared with research participants during research interviews. Reproduced with permission from goAct Pty. Ltd. Table 1. Summary of demographic information of Adelaide (S.A.)-based interview participants (n = 15). Participants Participants Position/Role Gender (Male, Female, Nonbinary) P1 Consumer M P2 Consumer NB P3 Consumer M P4 Consumer M P5 Consumer F P6 Consumer F P7 Consumer M P8 Consumer F P9 Consumer F P10 Psychiatrist M P11 Mental Health Nurse F P12 Psychiatrist M P13 General practitioner M P14 General practitioner M P15 OT/ADHD coach F N = 15 F:6 M: 8 NB:1 Table 2. Example Quotes to Illustrate Consumer Perspectives of Thematic Contextual Barriers to Better ADHD Care. Theme Example Quotes Ignorance and Prejudice (The lack of diagnosis over many years) made me feel a bit cross. … You know, I would have thought that … this information is readily available now. Maybe it just wasn’t readily available 10 years ago, I don’t know. … it just would have meant understanding myself a lot more. It would have given me a bit more compassion and you know, a little bit more awareness about understanding what it is that makes the makes me experience the world the way I do. P9 I’ve tried multiple people. Some GPs dismissed me, saying, “You wouldn’t have ADHD, otherwise you wouldn’t be able to manage to work and all that”. P1 So when I first went to my GP, things didn’t go as smoothly as I hoped. I tried explaining everything—how I felt, the symptoms, everything I read about ADHD. But because of my past with substance abuse and alcohol, my GP kinda brushed it off at first. … I felt super frustrated and defeated. P4 Wikipedia and YouTube are good for … science topics like physics and electrical engineering, but not for mental health. I find there’s a lot of pop psychology on there, and it’s not always accurate. P1 Going online … at first, it felt awesome because so much clicked, like, “That’s me!” But the more I dug, the more overwhelmed I got. There’s so much info, and it’s not all clear or trustworthy. P4 Trust “… are any of us safe in this digital world? It feels like our security is hanging by a thread sometimes”. P6 Wow, this sounds really promising! But I’m wondering, what comes after gathering all this data? How are we going to use it effectively? I mean, if I’m consistently checking in and answering questions about how I’m feeling, I worry it might heighten my anxiety or stress. It feels like I’d be concentrating on the negative emotions or symptoms, you know? P8Wow, this sounds really promising! But I’m wondering, what comes after gathering all this data? How are we going to use it effectively? I mean, if I’m consistently checking in and answering questions about how I’m feeling, I worry it might heighten my anxiety or stress. It feels like I’d be concentrating on the negative emotions or symptoms, you know? P8 Where are these questions coming from, and who’s behind creating them? P7 Impatience “I struggle with a lot of it(technology), particularly things like assessments that are supposed to be enjoyable. Yeah, no, kidding. I forget they exist. I get annoyed at the reminders because I do get pathological demand avoidance, where … as soon as it told me I have to do It, I can’t”. P2 … Previously, I kept my distance from technology; it was more stressful than helpful. Getting medication reminders four times a day would make me nervous. It felt like a constant reminder of my ADHD and other illness. Seeing all my symptoms written on one page? That is overwhelming for me. P8 The app has clean layouts, intuitive icons, and straightforward menu options, which I appreciate. However, having too many questions on a single page can be overwhelming and distracting, especially for someone with ADHD like me. P4 … Previously, I kept my distance from technology; it was more stressful than helpful. Getting medication reminders four times a day would make me nervous. It felt like a constant reminder of my ADHD and other illness. Seeing all my symptoms written on one page? That is overwhelming for me. P8 … having too many questions on a single page can be overwhelming and distracting, especially for someone with ADHD like me. P4 Theme Example Quotes Validation/ empowerment Oh, that’s awesome! I can share this app and my results with my mom. It’ll show her that it’s not all just in my head!” … When I go to see my GP, it always feels so rushed, and I completely forget what I wanted to share with him. Being able to print the findings report helps me stay focused during our talks. … it is hard for me to express my selves verbally. P1 “Getting insights on my health and comparing it with how I was doing last week can be a game changer. It’s like having a reality check. It’s not just about the data; it’s the empowerment that comes with it, making me think twice about my choices. If last week was a good week because I exercised more, it’s pushed me to keep that momentum. And if the app shows my mood’s been all over the place, maybe it’s time to ring up my doctor. It’s like having a personal health assistant in my pocket”. P2 Privacy and Data Integrity “Where is my everyday mood data going? I’m not convinced anyone would be interested in my anxiety, but it’s good to know. … I don’t want even my partner to find out about my anxiety and other issues, especially if he were to randomly use my phone”. P5 Talking about my mental health is very tough for me I’ve never been comfortable talking about my depression; I’ve always been that way. But my doctor believes I am depressed. P7 Tailoring I am taking stimulant medication, as well as the sex hormone, and I‘m not sure how this app could capture the combined effects of these medications on my mental health. P2 “The questions should resonate with my experiences and challenges. If the tool seems generic or not applicable to my specific situation, I might lose interest”. P7 …if it is actually, you know, a true representation of how I’m actually doing, I find my experience with that stuff is … it’s not really very accurate, right? … The nuances of how I’m doing are so complex, and so interconnected to things that have nothing..(and) everything to do with my mental health. P9 I get the simplicity, but it’s kind of dull for my taste. Wouldn’t it be cool if we could jazz it up with some colours and icons? Nothing too flashy, of course. And hey, letting us pick our own background colours—like other Apps … Features like voice commands, and easy readability can be helpful. … P6 I am taking stimulant medication, as well as the sex hormone, and I‘m not sure how this app could capture the combined effects of these medications on my mental health. P2 Access “I don’t like to go out unless I must, and with my family living 200 km away, I’m on my own a lot. This app can be a lifesaver, allowing me to assess myself. It’d be even better if I could log and track my feelings, sleep, and other symptoms to see if my medication is working. And ideally, share it with my GP. … I wish I could communicate with my GP in this app”. P3 I‘ve recently been diagnosed with ADHD and started medication. How can I tell if it’s working? I really need support in understanding what to expect from this treatment. P8 Table 4. Example Quotes to Illustrate Health Professional Perspectives of Thematic Contextual Barriers to Better ADHD Care. Theme Example Quote Complexity “To be honest, I prefer not to see ADHD patients. There are a few reasons for this. First off, there’s just so much paperwork and documentation. Every time I see an ADHD patient, I need to send their details to DASSA (Drug and Alcohol Services, SA). And then there’s the matter of medications. They’re not straightforward to adjust in terms of dosing, and there’s always this lingering worry about the potential for medication abuse. I‘ve heard of instances where patients take more than they should or their meds end up being used by someone else, maybe a family member or a friend”. P14 I never really received proper training for treating ADHD, and I don’t see many patients with the condition to begin with. And, honestly, the legalities also make it tricky. As a GP, I‘m not allowed to diagnose ADHD or start patients on medication. That’s something that needs a psychiatrist’s input. After they give a diagnosis and recommend the right dosage, only then can we move forward with treatment. So, all these factors combined make it a challenge for me. P14 Sustainability “So in terms of stickability the self-reporting needs to have enough sort of reinforcement. Qualities that the patient sees value … if it feels like a chore to use, they won’t stick with it. We want them to feel empowered, not overwhelmed”. P10 I would imagine … that after that initial motivation and drive wears off, they might forget that that app maybe exists. So forgetting to check in, you know, maybe their priorities shifts. And that apps no longer meeting their needs. So if I was designing … I‘d probably be looking at regular reminders, which had a consistent time of the day for them to check in. I guess I‘ve been trying to make that app simple as well. So if you’re thinking that potentially you might only captivate their attention for a short span of time, getting the most out of their attention. P15 I suppose that one risk I see with these kinds of apps is that … if I have to check on myself all the time … I’m also getting reminded that, well, there are these areas have got problems with, but what often happens when people get really better … they just want to, you know, go on and live life. P12 Theme Example Quote Transparent privacy and security frameworks I prefer a very organised approach when seeing patients. P13 “Above all, the data has to be secure. Knowing their personal health info is locked down tight would give us peace of mind”. P14 Streamlining I think to make GP’s lock into another system is a pipe dream. … Patients need to own the data, and then if you have a consult with a psychiatrist they can show the data and say, look, that’s how I’ve been tracking. P10 “(In an ideal situation) A tool that is secure, user-friendly, and offers features like one-click sharing of data, automatic trend identification, and integration with other health data could make self-monitored records more useful for both patients and practitioners”. P14 Connected care “I believe a collaborative system that involves the general practitioner, patient, and psychiatrist and effectively tracks treatment outcomes would be immensely helpful”. P14 … the platform that we use…helps with us scheduling clients having all the client details on there, we can use in case notes but most importantly, it helps us link in with telehealth, send emails to clients and text messages. … its pretty easy for the clients to use as well. When they’re joining telehealth appointments. All they really have to do is click the link put their name in and they join. … I don’t really have any complaints around that database. The other one (A database used elsewhere which the participant describes as clunky), I do have a lot of complaints around … it doesn’t support shared care with other practitioners. P15 Wishlist/ Need for tailoring I think it’s very difficult to create a list that’s relevant to everybody. Because people have very individual areas of their lives that they identify as having problems with. … So, for example, I’ve got one patient who…couldn’t go shopping independently in shopping centers. … But that might not be a thing for you know, the ten other people. … it would be good if it was customizable. P12 You know anything that’s a visual scale. So for example, if there was, you know, a total symptom scale that people fill out, but then the total score would be plotted over time. … It would be helpful because then you can see that, you know in one glance…(and) if there’s a report for the first assessments of baseline before treatment, for example, … and if they repeat those scores, it would be good to have that represented as a visual plot. But only for the symptoms that really matter. P12 I‘d love a simple way for patients to share their logs or data with me. Perhaps a one-click option that sends records straight to a secured platform? No more waiting for appointments to get updates. Charts and graphs! I‘d want the tool to identify and highlight trends automatically. Like, “Hey, notice more focus issues on Tuesdays?” or “Looks like mood depressions every evening”. That kind of insight can be game-changing … Think of it as a digital companion, not just a journal. Something interactive, insightful, and integrated. That’d be the dream toolkit. P14 “Their social life: Are they engaged in social activities, and how often? Substance use: Are they using any substances? Education: What is their educational background and status? How they cope with achieving their educational goals. Relationships: What is the nature of their personal relationships? Are they currently in a relationship? Or their emotional life in general. Living situation: Are they living with anyone? Is their housing stable? I also like to know their level of self-satisfaction. Are they making personal progress when compared to their past selves?” P14 Key Features of The ADHD Service Innovation Advantages of the Prototype ADHD Service Innovation Area For Enhancement 1: Privacy and Confidentiality Some participants with co-occurring mental health conditions expressed discomfort in discussing and recording sensitive information related to their mental health on the app. Likewise, health practitioners flagged privacy and confidentiality as important considerations. Recommendations Area For Enhancement 2: Tailoring: A one-size-fits-all approach might not cater to consumers with diverse and complex needs. Tailored experiences based on individual user needs, preferences, and mental health conditions enable streamlining and greater focus upon priority metrics, as required. Allowing ADHD care consumers to personalize question types, frequency, and focus areas will enhance the app’s usability. Enabling care consumers to tailor the app’s appearance to their preferences, can enhance visual appeal and user engagement. Recommendations Area For Enhancement 3: Sustainability App Interface: Tensions between the need for simplicity versus the need for sustained engagement. Not all care consumers are equally tech-savvy, and so ease of engagement, as much as the attraction of additional features are equal considerations to engage this (potentially impatient) audience and maximise the use of the newly developed functionalities. To help maintain the engagement of this population group it is preferable if questions are kept short, screen content is simplified, visuals and language are pro-actively inclusive, sensory engagement is heightened, personalisation features are enabled, and participants are provided ample guidance and support throughout the onboarding process. Recommendations The service innovation held great appeal and interest for most participants. Enhancing it with the following features could increase its appeal even further, especially considering the ADHD community’s need for visual stimulation and engagement to maintain interest: Streamline Content: Keep questions short. Simplify screen content. Emphasize inclusion: Use inclusive language, relatable imagery, and real stories from other people with lived experience of ADHD. Sensory Engagement: Integrate elements of music or art, voice recording, calendars, note-taking to enrich the user experience, ensuring ADHD care consumers feel positive and engaged while using the app. User Onboarding: Implement intuitive ‘How-To’ screens following the initial download and subsequent updates to guide care consumer’s effortlessly through the app’s features and functionalities. Explain the metrics rationale, perhaps with a contextual ‘i’ (information) graphic next to each question, and/or a ‘Why am I being asked this?’ link on relevant pages. Personalization Features: Offer customisable background colours and fonts, allowing care consumers to tailor the app’s appearance to their preferences, enhancing visual appeal and user engagement. This facility also supports streamlining of the monitoring functionality to enable greater focus upon priority metrics. Area For Enhancement 4: Robust Usability Feedback Mechanisms Frameworks for app user experience feedback and technical support within the app (or separately) are recommended to enable participants to share insights, experiences, and suggestions for improvements. Over time, this feedback can continue to guide iterative enhancements to the app’s content and features for sustainable improvement. Features that also allow participants the feeling and experience of connecting with others, by sharing experiences and gaining interpersonal support in managing ADHD offer significant value for this population group. Recommendations Area For Enhancement 5: Potential Future Developments To sustain consumer engagement in the long term, the continued utility and value of such a service will need to be readily apparent even after treatment has stabilised. Recommendations for added value enhancements include the provision of insight and coaching. The ADHD service innovation is in the early stages of development. Nevertheless, a range of advanced features were identified to be of interest. Recommendations Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. © 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Share and Cite MDPI and ACS Style

Patrickson, B.; Shams, L.; Fouyaxis, J.; Strobel, J.; Schubert, K.O.; Musker, M.; Bidargaddi, N.

Evolving Adult ADHD Care: Preparatory Evaluation of a Prototype Digital Service Model Innovation for ADHD Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024 , 21 , 582.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21050582

AMA Style

Patrickson B, Shams L, Fouyaxis J, Strobel J, Schubert KO, Musker M, Bidargaddi N.

Evolving Adult ADHD Care: Preparatory Evaluation of a Prototype Digital Service Model Innovation for ADHD Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2024; 21(5):582.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21050582

Chicago/Turabian Style

Patrickson, Bronwin, Lida Shams, John Fouyaxis, Jörg Strobel, Klaus Oliver Schubert, Mike Musker, and Niranjan Bidargaddi.

2024. “Evolving Adult ADHD Care: Preparatory Evaluation of a Prototype Digital Service Model Innovation for ADHD Care” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 5: 582.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21050582