Financing and Scaling Innovation for the COVID Fight: A Closer Look at Demand-Side Incentives for a Vaccine

As the COVID-19 pandemic accelerates, global leaders are quickly realizing that we need a bigger, better toolbox to effectively fight the novel coronavirus. In some cases, we need to quickly scale up production of existing health products and technologies—personal protective equipment (PPE) for health workers and others on the front-lines; ventilators for patients in critical condition, including ones that can work in low-income country (LIC) settings; effective antiviral drugs (pending better efficacy data from ongoing trials); and cleaning and sanitizing supplies for the broader population. In other cases, we need rapid research, development, and scale-up for completely new health technologies—point of care diagnostics, testing kits/platforms to be used in the community, new or repurposed therapies, and digital technologies to support epidemiological tracking and contact tracing. And then, of course, there’s the holy grail: development and widespread administration of a safe and effective vaccine that offers population-wide protection, ultimately allowing a global return to business-as-usual.

So how can we optimize our chances of getting these high-value health technologies as quickly as possible—and in the massive quantities we need? Many have (rightly) focused on getting urgent supply-side measures underway (i.e., financing through up-front grants, donations, or requisitions) for the most pressing supply constraints. These include investments in early-stage R&D and clinical trials; requisition of existing supplies for public health use; repurposing of existing manufacturing capacity for priority equipment (with calls to further expand this by government mandate); donations of goods from the private sector and international actors; and public-private partnerships to expand testing capacity.

But in addition to these important steps, we also need to tackle the demand (market) side of the equation, especially for vaccines. Whereas diagnostics can quickly come to market without safety risks for immediate use, and experimental therapies mostly relying on repurposing existing drugs with known safety profiles (where efficacy can be established within 1-2 month trials), an effective vaccine would only come to market after a far longer timeframe required to establish safety and efficacy in vast numbers of otherwise healthy individuals. A safe and effective vaccine would be enormously valuable, but the longer development timeline (at least 12-18 months) creates large market risk for potential developers (would people want to buy it?) on top of substantial scientific risk (would the product work?). By the time a vaccine comes to market, perhaps no one would want or need it anymore. What if the disease dies out naturally (as happened with SARS or MERS), is fully controlled (like the 2014/2015 West African Ebola outbreak), or enough people contract it and recover to establish herd immunity, perhaps as a result of a managed strategy of using testing to enable social distancing measures to be relaxed and economic activity revived? What if someone else comes to market first with a better vaccine and a company’s up-front investment was for nothing? What if we have enough affordable and effective therapeutic options available to manage the threat of COVID-19, such that a vaccine is no longer needed?

These are all great outcomes for society at large—but highly problematic if you’re a company considering whether potential R&D costs are likely to be justified by ex post facto sales of a successful product, and therefore highly problematic for the global community that desperately needs a vaccine in case those scenarios do not come to pass. We have also seen moves, discussed below, to restrict patent rights for COVID vaccines and therapies; there is a strong public health rationale for doing so, but perceived intellectual property (IP) risk will also inevitably deter private sector investment. The bottom line: if we want industry to invest up-front in the high-cost, risky business of vaccine development, we need to offer the promise of a predictable market for an effective vaccine that offers both access for all and a reasonable return on investment—de-risking market (commercial) uncertainty while still expecting companies to absorb the scientific risk that their products will fail.

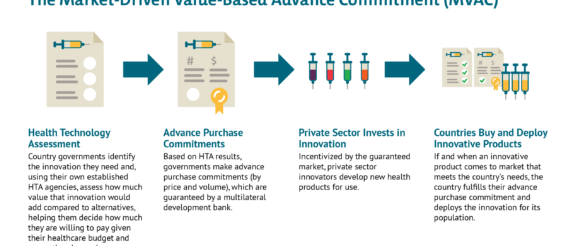

Since long before the novel coronavirus pandemic, CGD researchers, together with other colleagues, have worked to strategically de-risk health technology markets and strengthen demand-side incentives for priority diseases, particularly those affecting the poor and vulnerable in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). More than a decade ago, researchers at CGD helped develop the advance market commitment (AMC) used to incentivize development of a pneumococcal vaccine tailored to the LMIC disease burden. Once deployed at Gavi, the AMC helped accelerate investments in manufacturing capacity for rapid scale-up of the vaccine, which has saved an estimated 700,000 lives by 2020. More recently, building from the AMC model, we developed a new idea to help address intractable health challenges like tuberculosis where markets are failing—the market-driven, value-based advance commitment (MVAC)—which leverages value-based demand from LMIC payer agencies to create a market for new health technologies.

Below, we consider demand-side options for de-risking the market, incentivizing innovation, and scaling a potential vaccine for the COVID-19 crisis. Many of these same mechanisms could be used, with some adaptations, for other priority equipment and technologies, though the market failures there may be less severe. We focus here on the immediate crisis at hand, but this moment also offers an opportunity for governments to think bigger. How can all governments look beyond COVID-19 to other emerging and yet unknown pathogens—from novel viruses to drug-resistant bacteria—and put in place responsive, resilient, fit-for-purpose systems for high-value innovation and scale-up? And how can LMIC governments use demand side incentives to proactively tackle the routine and intractable health challenges their citizens face, from TB to HIV, snake bites, and renal failure?

Relevant Characteristics of a Potential COVID-19 Vaccine Market

To understand the potential scope and appropriate application of demand-side incentives, it’s worth outlining a few important characteristics of the likely market for a theoretical vaccine:

In short, we have potentially immense but unpredictable global need; we need solutions that combine the urgency of market entry with the imperative for quick global scale up, including to countries with less ability to pay; and we need a system that creates incentives for potential vaccine development through private investment while simultaneously recognizing public R&D contributions and the non-viability of a traditional sales strategy. If we succeed now, we can both accelerate the fight against COVID-19 and set the groundwork for a faster global response to the next crisis.

Potential Demand-Side Responses

Given this landscape, how could a demand-side incentive best be structured? Below we consider three high-level scenarios, with some brief thoughts on their potential upsides and pitfalls:

Like the AMC, the MVAC de-risks the commercial market, resolves potential IP issues, and offers an avenue for widespread, rapid uptake across countries with divergent abilities to pay. But the MVAC is a superior option because it incorporates flexibilities to reward value—and ensures we continue to incentivize investments in the best (and safest) possible products. The MVAC signals to industry that the market values their up-front investments and those investments have the potential to pay off down the line. And beyond the immediate challenge at hand, the MVAC sets a sustainable precedent for future emerging challenges, helping prove to developers that a market will exist for high-value innovations and they should invest aggressively to tackle global challenges.

Work is needed to explore these options. In our view the MVAC offers a better route as it differentiates price according to efficacy, so incentivizing development and use of vaccines with higher rates of disease prevention, while ensuring that vaccines are available at manufacturing cost for LICs. Without consideration of value, countries risk getting locked into purchasing inferior or cost-ineffective products that divert scarce resources from other potential COVID-19 responses, including potential therapies, non-pharmaceutical interventions like testing/contact tracing, and later, superior vaccines that may be boxed out of the market if all funding immediately flows to a first, poor-value or minimally efficacious entrant. Though the consideration of vaccine value for a pandemic virus will necessarily differ from routine vaccination—in large part due to the enormous social and economic costs of existing non-pharmaceutical interventions—it can nonetheless build on existing systems for vaccine value assessment that are well-established, supported by WHO guidelines, and used to inform listing decisions and pricing in countries like the UK as well as in LMICs like Thailand, the Philippines and the PAHO region. Adjustments can be made to ensure that any push funding of a successful candidate is taken into account, and that value-based prices for HICs and MICs only apply to the volume required for the innovators to get an appropriate return on investment, with much lower prices applying after that point.

Additonal Design Issues to Consider

Action is required now to set in place appropriate funding and incentive tools. We have made the case for a coordinated advance commitment that can incentivize private sector delivery of high-quality vaccines against COVID-19 while ensuring that the populations of LICs gain access through commitments on price, investment in additional manufacturing capacity, and funding to support procurement.