Guest post: Advancing Inclusive Innovation and Entrepreneurship through the Patent System

By Colleen V. Chien, Professor of Law; and Jonathan Collins, Zachary J. Daly, and Rodney Swartz, PhD, all third-year JD students; all at Santa Clara University School of Law. This post is 4th in a series about insights developed based on data launched by the USPTO.

“To genuinely advance development and human progress, we should all work to expand the innovation neighborhood and make sure everyone knows that they, too, can alter the world through the power of a single concept.”

— June 17, 2020 USPTO Director Andre Iancu

As we await a life-saving COVID vaccine, each new day reminds us of the inequalities that the pandemic has actually laid bare. 30% of public school children do not have web or a computer system in the house, making school reopenings an immediate concern. Black and brown people, are passing away at a much greater rate from Covid due to a complex set of factors, and are at greater threat of lacking access to prescription drugs because of expense.

Though just one part of the bigger innovation ecosystem, the patent system has a crucial function to play in advancing inclusive innovation. Below we construct on the USPTO’s recent management and the AIA’s current inclusionary policies (local offices, pro se/bono supports, fee discounts) to supply a couple of concepts: being a beacon for the development requirements of underrepresented populations, attending to the patent grant space experienced by little innovators, diversifying inventorship by diversifying the patent bar, and establishing and reporting innovation equity metrics. These ideas bring into play the paper by among us, Inequalities, Innovation, and Patents and earlier work, and the continuous efforts at the USPTO to “widen the innovation neighborhood.”

Be a Beacon for the Unique Development Needs of Underrepresented People and for Tech Transfer

Historically, innovation for underrepresented and underresourced groups has been underfunded. For example, Senator and VP candidate Kamala Harris just recently introduced a bill to fund research study on uterine fibroids, which, though getting little research study attention, disproportionately effects African-American females at a rate of 80% over their lifetimes. Closing the broadband gain access to gap will need ingenious technology services to handle the “last mile” problems that face rural and underserved populations. The USPTO can use its powers to speed up development to meet the special needs of underrepresented and underresourced groups, consisting of, as was done in the context of the Cancer Moonshot initiative, identifying appropriate patents and applications and integrating patent data with external data sources for example from agencies like the National Institutes of Health and Food and Drug Administration. These efforts bring connect patented inventions to “upstream funding and R&D as well as downstream commercialization efforts.” To speed COVID development, the agency has actually taken a number of other actions including delaying or waiving fees, focusing on examination, and releasing a platform to help with connections between patent holders and licensees. These capabilities might be directed to top priority equity areas, which are positioned to benefit especially when personal and public funding is at stake.

Expand Equality of Chance by Resolving the “Patenting Grant Gap”

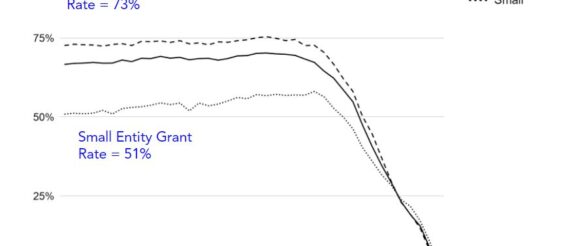

When startups and development entrants patent, great results often follow: novice patenting is connected with financial investment, employing, and economic movement. But in a lot of cases, the applications sent by little entity innovators don’t actually develop into patents. Using open government data helpfully provided by the USPTO Open Data Website (beta) we find, as recorded in Fig. 1 below from the paper, that small entities are less likely to succeed when they make an application for patents: by our quote, applications filed 10 years ago have become patents 73% of the time vs. 51% for small/micro entities, a 40%+ difference.

Others consisting of work by former USPTO Chief Economist Alan Marco, have reached similar conclusions. Empirical studies have likewise found that creators with female sounding names, or who are represented by law companies that are less familiar to patent inspectors are less likely to get patents on their applications than their counterparts. (source: Colleen Chien, )

The distinction in allowance rates might be due to any of a range of elements, for example, a higher abandonment rate or distinctions in the kinds of patents sought. The possibility of implicit bias– based upon inventor, or company name– is also worth investigating further; the USPTO isn’t the only federal company where the possibility of predisposition has been documented. But no matter the reason, ungranted applications to underrepresented groups present not just possible equity issues for society however likewise financial problems for the agency: applications that never ever develop into patents do not create issuance and maintenance charges.

One solution may be to try to improve the quality of underlying applications. As previously recorded using PTO office action data, the applications of reduced entities are much more likely to have 112 rejections, and in specific 112(b) rejections. (Fig. 5A) An absence of “applicant readiness,” as explained by inspectors, might be one offender. (source: Colleen Chien, (2019 ))

A promising approach as gone over formerly by among us would be to equalize access to preparing tools and aids, which are frequently utilized by advanced candidates to, for example, inspect the correspondence in between claim terms and the requirements. Using mistake correction innovation to level the playing field in government filings, through public and private action, is precedented. Enhanced application quality advances the shared goal of compact prosecution, and to that end it is motivating to see that the Workplace of Patent Quality Assurance, in their ongoing work to improve applicant readiness, is reportedly working to “recognize opportunities for IT to help with quality enhancements early at the same time.” Such efforts could go a long way to deal with both the equity and economic challenges described above. We motivate continued investigation and prioritization of public and personal efforts to attend to the “patent grant gap” in assistance of wider inventorship and involvement in development.

Diversifying Inventorship by Diversifying the Patent Bar

As argued in the paper, patenting is a social activity that depends on social connections -“who you understand and who you can hire.” However access to patent skill is unequal– Sara Blakely, the creator of Spanx, has actually reported that she might not find a single female patent attorney in the state of Georgia to file the patent upon which she developed her billion-dollar undergarments empire. To sit for the patent bar generally requires a science, innovation, or engineering degree. But since of their underrepresentation amongst STEM, engineering, and computer technology graduates, females, Black and Hispanic individuals are disproportionately left out from involvement. The technical degree requirement especially disadvantages those with style experience however not engineering degrees, who are typically women, and who might otherwise want to prosecute design patents over fashion or commercial design, Christopher Buccafusco and Jeanne Curtis have kept in mind. Unwinding the technical degree requirement would enable diversification of the patent bar, in support of diversifying inventorship and entrepreneurship.

Establish and Focusing On Innovation Equity Metrics and What Works

While each year the number of brand-new patent grants is revealed, maybe the patent statistic that has catalyzed the most action just recently is the USPTO’s groundbreaking Development and Potential series of reports which, for the very first time, formally documented that only 12-13% of American inventors are ladies, and Director Iancu’s leadership and his personnel on the problem. This report has triggered conferences and toolkits, and spurred business to revisit their patent programs and pipelines. As extra resources are invested into making development more inclusive, “innovation equity metrics” that make the most of the granularity, quality, and consistency of patent information, which track, for example “inventor entry” and “concentration” and the geographic circulation of patents, as shown in the paper, deserve purchasing. Improved information collection, for example, of race and veteran status data, and federation and coordination with other datasets, for example held by the Small Company Administration, or in connection with the Small company Development Research program, and Census could go a long way. Doing so would permit more routine reporting and analysis of the overall health of the development environment, which, by a couple of measures seems waning: as explained in the paper, patenting by new entrants is down while the concentration of patent holdings is up. Studies of underrepresented inventors, and what have been enablers and blockers, can also lend inform the advancement of policies of inclusion.

Conclusion

Just one part of the larger development ecosystem, the patent system’s enduring commitment to a variety of innovators and equivalent chance position it well to answer the call of the current moment, for higher addition in development. We encourage readers with concrete ideas about how to advance addition in innovation, through the patent or other governmental levers, to send them to the DayOneProject, which is gathering ideas for action for the next administration. For more, likewise take a look at the current Brookings Report on Broadening Innovation by Michigan State Prof. Lisa Cook, a leading financial expert (see, e.g. the NPR World Cash podcast, Patent Racism, about her work).

The authors represent that they are not being paid to take a position in this post nor do they have any conflicts of interest in the subject talked about in this pos