How Social Influences Impact Tech Innovation

How Social Influences Impact Tech Innovation

Posted on 21st July, 2017 by

Zach Fuller

in Innovation

We know we cannot predict the future, yet the fortunes of investors and entrepreneurs continue to be made and lost in trying. Whether you are Nostradamus or a staff writer on Black Mirror, the future remains an amorphous misfit, forever teasing our understanding of how to prepare for its revelations.

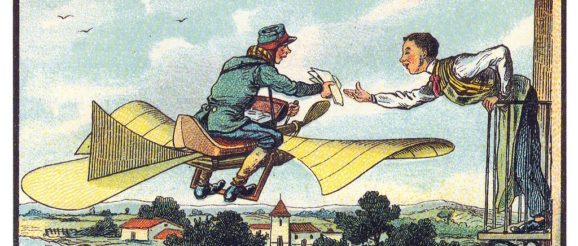

However, this does not stop us from gleaning insight from the past, and some of the most glaring omissions in predictive discourse are the social influences on the development of technology. Back in 1986, the acclaimed Russian Science-Fiction author Isaac Asimov’s Future Days compiled a collection of postcards from late 19th Century France, featuring sketches by the artist Villemard imagining the year 2000. With hindsight’s benefit, they vary in accuracy from the astute (international video calls) to the amusing (miniature flying contraptions for the postman). Nonetheless, to observe how Villemard and other earlier societies have thought about the future provides a remarkable insight into our own perceptions of emerging technologies and how the social factors of our era can mislead us in predicting which will have the greatest impact.

Flight Mania and Artificial Intelligence

Human history is suffused with the aspiration to flight from Daedalus and Icarus in Greek mythology to the Warring-States era of China’s bamboo-copter. Late 19th Century French society, however, was particularly obsessed with aviation, a collective focus which took form in the precursor to modern flight, ballooning.

It was on French soil that the Montgolfier brothers performed the first unmanned balloon flight in 1783, triggering a golden age of flight innovation in the country that would see the invention of the hydrogen balloon, the first balloon to cross the English Channel and the first steerable hot-air balloon all accomplished by French inventors and engineers. Whilst it was originally decreed by King Louis XVI that condemned criminals would be the first to try new technologies (just in case they should not work), these developments were lent an air of respectability by the special interest taken in ballooning projects by the Marquis and French nobility at the time. Launches were quickly turned into spectacles, with 400,000 people (including Benjamin Franklin), attending the December 1783 launch of the first hydrogen powered balloon. It’s hard not to draw immediate parallels with live streams of Apple’s product launches.

This patronage by the high society of the time is crucial to this story’s application in modern tech predictions. Present day Silicon Valley is far removed from its Research and Development roots in the 1950s; it is now a globally renowned powerhouse of innovation venerated by politicians and celebrities alike. Recently elected French President Macron has spoken of transforming France’s economy into, ‘a Start-Up nation’ whilst Hollywood actors and sporting idols have rushed to ally themselves with technology and open Venture Capital firms (with varying degrees of success). Public perceptions of CEOs of tech companies are increasingly dated; they now appear on the cover of Vogue and marry Victoria’s Secret models. These developments rhyme with 19th Century French society and aviation, as inventors and engineers specialising in flight benefited from a similar impetus to their social prestige.

The desire to be within such company is arguably present at every stage in recorded human history, yet it has a heightened resonance in post-revolutionary France – this being the society that arguably invented modern conceptions of meritocracy and social mobility. Such ideas are not confined to academic sociology; they are reflected in the literature of the time through Flaubert’s Madame Bovary and later Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. The first major French silent film was Georges Melies’ A Trip to the Moon in 1902 – you begin to see the pattern. Achievement in aviation was a conduit to a better life and accounts for the social framework within which Villemard made his predictions of the future.

Yet what Villemard could not have foreseen is that many of his problems solved by flight were solved only a few decades later by something else: the car. His postcards pre-date France’s automotive industry by just a few years, with Renault and Peugeot being formed towards the end of the century. That the car solved many of these issues which Villemard had theorised would be improved by flight inevitably begs the question: could a single invention in the areas of haptics, quantum computing and AI render contemporary tech manias (data analytics for example) suddenly irrelevant?

Anyone creating something new wants the world to appreciate their work; whether you are an artist, engineer or entrepreneur. Because developments in flight were in vogue at the time, you begin to see why those aiming to predict the future would have perceived these developments, much in the same way a young entrepreneur in 2017 would look to the future and see: Streaming, AI, Machine Learning, Blockchain, IOT, Fintech, Data, Big Data and even Bigger Data!! Villemard’s postcards reveal that it is important to remember that these buzzwords and manias are frequently ephemeral, and are as easily disrupted as flight hubris was by the invention of the car, yet can inhabit the thinking of creators for decades before ultimately being expunged. What we can take away from this is that what is celebrated by a society often becomes the framework for those inventing the future, and it is rare that more logical extensions of our present worldview materialise in the way we currently think that they will.