How to fix Washington’s anti-innovation rules on carbon-reducing projects

While much of the focus on Washington state’s climate policy is on government regulation and spending, we are not going to effectively reduce CO2 emissions without significant new innovation in a range of areas.

Despite calling innovation Washington’s “secret sauce,” Governor Inslee’s approach to climate change has been decidedly focused on using government to target favored technologies rather than providing a level playing field for environmental entrepreneurs. The Department of Ecology’s rules regarding carbon offsets in the state’s new CO2 regulations are good example of how state climate policy restricts innovation while spending taxpayer money on a range of government programs with few requirements for success.

Carbon “offsets” are simply projects that reduce CO2 emissions. A project that collects methane from landfills and uses it as fuel is an “offset” if someone else pays for it. That same project paid for by the government, however, isn’t perceived in the same way as an “offset” (for some reason) even though it is identical.

The benefit of offsets is that they incentivize innovation by rewarding new ways to cut emissions at low cost. Rather than forcing me to spend tens of thousands more for an electric vehicle, I can spend a fraction of that to reduce the same amount of CO2 emissions in some other way, like planting trees, capturing CO2 or methane emissions, or storing carbon in the soil.

The combination of flexibility and innovation make offsets an effective and inexpensive way to reduce CO2 emissions and the risk from climate change.

Department of Ecology staff confirmed this last year when they released the final cost-benefit analysis of the state’s new tax on CO2 emissions known as the Climate Commitment Act (CCA). The report noted that using offsets made it easier to reduce the same amount of emissions for lower cost. It found, “If covered and opt-in entities purchased offset credits in lieu of purchasing allowances, it would reduce market demand, putting downward pressure on allowance prices…” Offsets are intended to create flexibility and encourage innovation while meeting the same CO2 targets.

Despite that promise, the offset system created by the Department of Ecology in compliance with the CCA is cumbersome and is overtly anti-innovation.

It should be said at the outset that this is intentional. The primary goals of the legislature when creating the cap on CO2 emissions were to generate revenue for legislators to use and to reward special interests. Innovation and regulatory flexibility that make it less expensive to cut emissions are better for the economy, businesses, and consumers, but mean fewer dollars go to state coffers. So, the CCA was written to limit the innovation that will be necessary to meet the state’s extremely tight CO2 goals without harming the economy and families.

A look at the process to create certified offsets shows how high the barriers are.

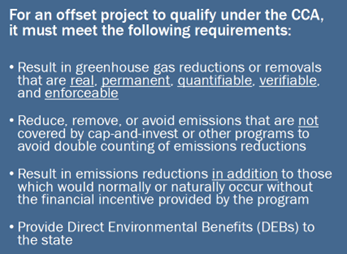

The Department of Ecology notes that carbon offset projects must reduce CO2 emissions in ways that are “real, permanent, quantifiable, verifiable, and enforceable.” The CO2 that is avoided must not be covered by another other existing law. For exampdle, reducing methane emissions – a common carbon offset project – from landfills wouldn’t count because the state adopted a law covering those emissions already.

The Department of Ecology notes that carbon offset projects must reduce CO2 emissions in ways that are “real, permanent, quantifiable, verifiable, and enforceable.” The CO2 that is avoided must not be covered by another other existing law. For exampdle, reducing methane emissions – a common carbon offset project – from landfills wouldn’t count because the state adopted a law covering those emissions already.

The CO2 reductions must also be in addition to what would have occurred without the offset project. For example, a company that planted trees might not qualify for CO2 reductions if they were going to plant those trees anyway.

Finally, any CO2-reduction projects must provide “direct environmental benefits” to Washington state. A project that reduces CO2 emissions that are real, permanent, quantifiable, verifiable, enforceable, and are more than without the project only count if the offset creates environmental benefits for Washington. A project in Wyoming that reduces CO2 emissions for a fraction of the cost would probably not be allowed. California has a similar rule, but only requires half of offset projects to meet this requirement.

The offset rules limit allowable projects to four categories that have been pre-approved by the agency. These include forestry projects, urban forestry, projects related to livestock, and reduction in certain ozone-depleting chemicals. Any project that falls outside those categories would have to go through rulemaking including public comment. New innovation would have to be approved by the Department of Ecology in a rulemaking.

That is just the beginning.

After a category has been approved individual projects must then go through a five-step process. Projects must be submitted to a state-certified offset registry before it can begin operations. Once the project has completed emissions reduction a third-party must review the quantified CO2 reductions. That report is then reviewed by the offset registry that issues credits. Finally, the Department of Ecology must review all materials and approve them for inclusion in the state’s CO2 market.

Even after all of that, the CCA limits the percentage of offset credits businesses can use to reduce emissions to five percent of their total covered emissions and an additional three percent from projects on tribal lands. As far as the environment is concerned, there is no reason for this limit.

Even after all of that, the CCA limits the percentage of offset credits businesses can use to reduce emissions to five percent of their total covered emissions and an additional three percent from projects on tribal lands. As far as the environment is concerned, there is no reason for this limit.

All offset projects must meet very high standards of proof including certification from both a third-party organization running a registry and the Department of Ecology. The Department also approved the two organizations running the registries, saying they have a “track record of excellence.” I asked a spokesperson for Ecology to explain what that meant. She responded that “Each of these nonprofit registries has a track record more than 20 years long, and both have more than a decade of experience verifying offset projects in California’s cap-and-trade system.”

If all of that is true, then why limit the number of offsets that can be used?

The simple reason is that the priority for the legislature is increasing state revenue. When businesses purchase offsets, they pay the organization reducing emissions rather than paying a tax to the state for an allowance. Using offsets means lower costs for businesses – and for their customers – but less money to the state. So, legislators put a strict cap on the use of offsets, even though the limit increases the economic impact of the CCA and limits opportunities for climate innovation.

The Department of Ecology’s own analysis admits that using offsets reduces the cost of compliance. That was confirmed in Ecology’s training on offsets on May 10. Ecology staff noted that the cost of offsets in California is lower than the allowance price and is expected to be the same here. That is notable since Washington’s allowance price is 75 percent higher than in California, making offsets significantly less expensive than the current amount of Washington’s tax on CO2 emissions. Ultimately Governor Inslee and the legislature decided that high economic costs and more money to government – even though they don’t add any emissions reductions – are better than low economic costs and more money in the pockets of businesses and state residents.

In addition to increasing costs, this approach also undermines innovation that will be needed to efficiently reduce emissions in the medium and long run.

The system of multiple layers of regulation – approving types of credits, multiple restrictions on offset projects themselves, requiring numerous checks, and limiting use of offsets – means innovators looking for a place to try new projects will find Washington state inhospitable. In a state where Microsoft, Amazon, and other businesses are pledging to spend huge amounts of money on reducing emissions, Washington’s own rules seriously narrow the range of innovations that can tap into the resources available from organizations covered by the CCA.

Ironically, the same legislators who make it so difficult to create carbon-reducing projects are spending millions of dollars on far more dubious projects they claim will reduce CO2 emissions, but don’t have to go through the same regulatory steps.

For example, the recent state budget provides $30 million for “for organic agricultural waste and greenhouse gas emissions reduction through climate-smart livestock management,” which is one of the categories of offsets Ecology has already approved. The grant process does not require the level of scrutiny those same projects would be subjected to if they were carbon offsets. Funding for projects must only “consider” the “amount of greenhouse gas reduction that will be achieved by the proposal…”

And if the government-funded projects fall short of the promised results, there is no requirement for taxpayer dollars to be returned, as there is with carbon offsets.

This is perhaps the clearest indication that the priority of the Climate Commitment Act is to generate tax revenue rather than effectively cut CO2 emissions. Effective, but private, projects are saddled with numerous restrictions. Government-run programs have few requirements and only loosely held to standards of success.

Ultimately, despite rhetoric from the governor about innovation, the CCA’s rules effectively undermine new opportunities at innovation. They are intended to make innovation difficult. The strict limits on offsets hinder access to effective and low-cost alternatives to the allowances which are very expensive compared to California.

The focus of climate policy should be to reduce CO2 emissions effectively and inexpensively. Regulators and legislators should make significant changes to the system to promote innovation and reduce costs for Washington residents while meeting CO2 targets.

Without these changes, the CCA’s current rules make cutting CO2 emissions needlessly expensive and create barriers that make innovation extremely difficult. Washington state’s arbitrary CO2 emissions targets will make reaching those goals difficult and costly. Unless the governor and legislators make the rules more flexible, Washington residents will continue to pay costs that are much higher than other states with similar programs without providing any additional environmental benefit.