Innovation: An Inspiring Story from the Holocaust | Roots and Wings

The Holocaust[1] was a time of horrifying acts. Between the years 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its allies were responsible for the deaths of six million Jews in Europe. It is a time we cannot afford to forget lest we are led into similar situations in the future. The holocaust was also a time of innovations that saved many lives. There was no blueprint for these innovators. They reached into their hearts to make a difference. One such innovator was Sir Nicholas Winton.

The Accidental Innovator

Nicholas George Wertheim was born in Hampstead, London, England, on 19 May 1909, to German Jewish parents. The family changed its name to Winton and converted to Christianity in the process of getting integrated into English life. Nicholas was aware of the Nazi activities and had a perspective based on his heritage. In 1938, Winton was a stockbroker looking forward to a sports holiday. Just before he left for the holiday, his friend Martin Blake wrote to him from Prague about an interesting assignment he was involved in as a member of the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia. The message said to cancel his trip to Switzerland and come to Prague instead.

In Prague, Winton visited numerous refugee camps in German-occupied Sudetenland and saw firsthand the horrible conditions under which the refugees were living. British activists in Czechoslovakia were doing all they could to help the refugees. Winton was particularly concerned about the children and felt he could do something to help them. He wondered if he could find homes for the children in England.

The Startup

Winton, Martin Blake, and Doreen Warriner (Blake’s colleague, who was instrumental in alerting Winton about the state of the children) started collecting the names of the families who wanted to send their children to England so that they can be safe. They did this operating from a hotel room in Prague. Winton then returned to England to work on the plan to bring the children over.

Winton knew getting hundreds of refugees over to England required careful planning and the help of many supporters. The first step was the discussions with the British Government, who were willing to let the children enter the country only under very strict conditions.

Winton continued to work as a stockbroker during the day and worked on his plans in the evenings to bring the children over. His partner Trevor Chadwick continued to work in Prague.

There was already an effort to save the German and Austrian Jewish children called “Operation Kindertransport”[2]. The British public donated generously to this effort to the tune of 500K British pounds in six months. Close to 10,000 children were given homes in Britain under this program. However, it did not cover the children of Sudetenland.

The Operation

On his return to London, Winton met with the Home Office. He was told that in order to get the children to be transported from Sudetenland, and then to be placed in foster care in Britain, he has to meet two conditions — one, there must be a guaranteed foster care, and two, a deposit of 50 pounds to pay for the return travel, for each child. The parents of the children were too poor to afford the sum. It is said that Winton took the stationary of The British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia, added “Children’s Section” to the heading, named himself the chairman, and set out to get donations from the British public. The Children’s Section’s staff consisted of volunteers, including his mother and his secretary.

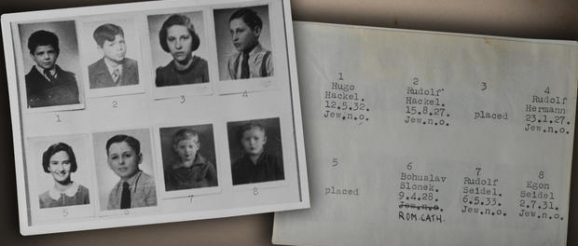

Winton worked tirelessly to secure funding by advertising in newspapers and through churches and synagogues. He was prepared to spend his own money if needed. The marketing push for his operation was to share the photographs of the children, hoping to raise sympathy from the prospective host families.

On March 14, 1939, the first set of children left Prague by air and were placed in foster care. This was followed by seven more rescue trips which took the children from Prague by train, followed by a boat ride across the English Channel, and finally a train to the Liverpool Street station where the foster parents collected them from the station. The last mission took place on August 2, 1939. In all, over 600 children were rescued. On September 1, 1939, a train with 250 children was to leave Prague, but Hitler invaded Poland on that day and the mission was aborted.

Risk Taking and Innovation For Good

Innovation is not only about creating a new product. Entrepreneurship is not only about creating a Unicorn. It is also about creating processes that benefit humanity. Winton had multiple stakeholders — the parents of the children, the children themselves, the British Home Office, the British public, and the foster parents. He managed to satisfy them all with the help of his teams in Prague and London. He went about this quietly until 50 years later his wife Grete learned about it from his scrapbooks she found the attic, and the world came to hear about his story. His story was told through documentaries and articles. His motto, “If it’s not impossible, there must be a way to do it” formed part of the title of his daughter’s book[3].

Winton had been interviewed many times. In answer to a question on why he did what he did, Winton answered[4]:

“’One saw the problem there, that a lot of these children were in danger, and you had to get them to what was called a safe haven, and there was no organization to do that,’ he told The New York Times in 2001. ‘Why did I do it? Why do people do different things. Some people revel in taking risks, and some go through life taking no risks at all.’”

Sir Nicholas Winton died at the age of 106, on July 1, 2015.

I hope we never have to live through another event like The Holocaust, but it is heartwarming to know that during times of great trouble we have innovators like Winton who step up, take risks, and make a difference in the lives of many.

[1] Wikipedia. (July 26, 2021). “The Holocaust”. Retrieved July 27, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Holocaust

[2] The Story. “Nicholas Winton. The Power of Good”. Retrieved July 27, 2021, from http://www.powerofgood.net/story.php

[3] Winton, B. (September 16, 2014).”If it’s Not Impossible: The Life of Sir Nicholas Winton”. Ditton Press.

[4] “Sir Nicholas Winton”. Biography. Retrieved July 28, 2021, from https://www.biography.com/activist/sir-nicholas-winton