Investment alone cannot shrug off effect of communist years on innovation in eastern Europe

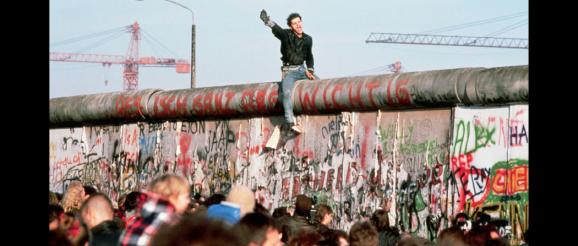

New research shows how East Germany and other former Eastern bloc countries remain affected by the legacy of the command economy and the shock transition to capitalism The negative impact on innovation ecosystems in former East Germany of nearly half a century of the command economy, followed by the rushed integration with West Germany, cannot be solved simply by investment and subsidies, new academic research suggests. The study investigates reasons why there remains a gap in innovation performance between East and West Germany, looking at the impact of a socialist structure in the East and also the consequences of East and West Germany merging almost overnight. On both counts, the east of Germany lost out. Despite the best efforts of the German government since the early 1990s to level up its eastern regions, including overall investment of over €1.2 trillion, the innovation performance gap remains. “Remarkably, massive policy support with high subsidies for innovation activities could not prevent the increasingly large East-West gap,” the paper says. “This failure casts doubt on hopes for a quick recovery from radical transformation processes.” If anything, huge subsidies are creating a different type of problem said Michael Wyrwich, associate professor at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and one of the paper’s co-authors. The socialist years led to what he calls a lower level of ‘systemness’, meaning the level to which local actors in an innovation ecosystem work together and share knowledge. “If you analyse data on network relationships and joint collaborations, you observe that in East Germany there is lower systemness,” Wyrwich said. Subsidies alone cannot solve this. Researchers or entrepreneurs might join a collaboration because of subsidies, but these might not be the most effective partnerships or what is best for local innovation, said Wyrwich. “That is an artificial effect that is not really helping to develop a self-sustaining innovation system.” Trust is another factor. The years of authoritarian rule in East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), eroded trust, not only in authorities but also in friends, neighbours and business partners. Investment alone cannot solve this. “I think the legacy of the effects of the socialist system on innovation will stay for some time, especially on the more intangible elements such as trust,” Wyrwich said. While the research focused on the GDR, the same could be applied to other former Eastern Bloc countries that are now part of the EU. Wyrwich and his colleagues at Friedrich Schiller University Jena are working on expanding their research to these countries. The finding that throwing money at an issue with long historical roots might not entirely solve the problem, undermines an argument long mooted by certain academics and politicians in western Europe that central and eastern European countries should simply increase investment in research and innovation themselves to close the gap. Wyrwich said it was important to look at fostering trust, increasing access to global knowledge flows and improving governance structures that can often be weak in the region. “Just fiscal transfers alone will not solve the problem entirely,” he said. Impact on innovation A Communist political model isn’t necessarily an obstacle to innovation in highly focused fields. The former Soviet Union, for example, at times outpaced the US in space technology in the 1950s and 60s before the US put the first astronauts on the moon in 1969, leading the USSR to gradually scale down investment into the industry. But beyond certain specialised fields, the top-down approach is generally not conducive to innovation. Wyrwich’s research looked at patenting data, finding that the seamless flow of research to product necessary for innovation, was largely absent in the GDR. The state would decide what product was needed and then companies would look for a patent – almost always owned by the Academy of Sciences – and try to come up with that product. “It rarely worked out,” Wyrwich said. There was no ground up initiative and hardly any customer feedback, meaning demand was not taken into consideration. A good example is microelectronics. By the end of the 1980s, a one megabit chip manufactured in the GDR cost 500 deutschmarks, one made in Japan four deutschemarks. GDR’s massive subsidisation of innovation in microelectronics was “a huge miscalculation”, Wyrwich said. Countries such as Poland or Czechia were further hampered because they did not have a strong industry base pre-World War Two, something the GDR have. With the west’s embargo on technology imports, Communist bloc states lagged significantly behind in innovation when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. The rapid transition to a market economy and integration with the west did little to close that gap. Reunification On the face of it, German reunification should have benefitted innovation in the eastern regions. An increased richness and diversity in the knowledge base, more opportunities for cooperation, resource mobility and greater competition should have seen innovation boom, the paper notes. Instead, it only helped the west and the eastern regions suffered from what are today still common problems. Brain drain was a huge issue. Only around 40% of GDR’s scientific employees stayed in research after reunification, while 25% of inventors involved in patenting pre-reunification ended up moving to research positions in West Germany after the merger. Another issue was that the East had for so long sought to compete in the same technology fields as the West, but after reunification it was far behind. The whole system in the GDR, Wyrwich said, was geared towards benchmarking with West Germany and trying to copy it or catch up, without developing its own technology focus. After reunification, the East’s technology industries became largely obsolete. More recently, EU-level policies have been brought in to try to address this. The Smart Specialisation strategy, introduced in 2011, aims to help regions focus on their specific technological strengths, to avoid overlapping or clashing with other European regions. This is a useful approach, Wyrwich said, but countries and regions now also need to position themselves to compete globally, not just within the EU. While Wyrwich research shows Communism and the transition to a market economy had a profound impact on innovation, it is hard to say how long this effect will last. In terms of the more intangible factors, such as community trust, it could be generations. Wyrwich said he can envisage some regions in the former Eastern Bloc eventually catching up to the EU average in terms of innovation, such as capital regions around Prague or Warsaw. For others, it could take a lot longer. There is little doubt that the shadow of the socialist legacy still hangs over the region.