It’s official: The 2010s will go down as a lost decade in American entrepreneurship – Economic Innovation Group

by Kenan Fikri and Daniel Newman

On many measures, the 2010s was one of the least entrepreneurial periods in the country’s recent history. This insight is confirmed by the latest release of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics, which establishes the full baseline trend in American startup rates leading into the pandemic. Startups also are employing fewer workers than in the past: new firms hired 2.4 million workers in 2019 — the same numbers as nearly 40 years earlier (in 1982), when the workforce was 57 million individuals smaller.

The startup rate remained little changed for the fourth straight year.

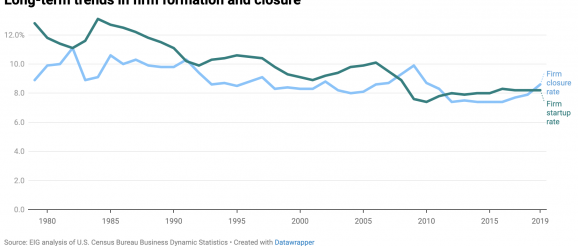

The country’s startup rate, or the share of all firms in the economy that were formed within the past year, stood stable at 8.2 percent in 2019, essentially unchanged from 2018 and only slightly above the all-time low of 7.4 percent reached in 2010, after the Great Recession. The startup rate remains one of the few economic indicators that never recovered from the 2007-2008 global financial crisis.

In absolute terms, 2019 saw the highest volume of new firm starts since 2008 (although nearly 100,000 fewer than in 2006, the year with the most on record), for a total of 438,000 new firms launched. However, an off-setting 459,000 firms failed in 2019, meaning the U.S. economy did not generate sufficient new firms to replace those it lost. In other words, while the firm death rate recovers towards historical norms, the startup rate has been languishing.

Startups employed 2.4 million workers in 2019 — the same as in 1982.

New firms employed 2.4 million workers in 2019, a high-point for the decade. However, that level is comparable to the number of workers employed in American startups in 1982, when the workforce was 57 million individuals smaller. Startups’ 1.8 percent share of total U.S. employment in 2019 remained flat, near all-time lows, following a long-term decline that set in during the late 1980s.

Conversely, the share of all American jobs now housed in older firms, defined here as those at least 16 years old, reached an all-time high in 2019, just under the three-quarters mark at 74.9 percent.

Most states trail the national startup rate

Twelve mainly Western and Southeastern states had startup rates higher than the national 8.2 percent in 2019, a pattern that closely tracks with faster state population growth. Nevada (10.4 percent), Florida (10.2), Utah (10.0), Idaho (9.6), and Texas (9.6) registered the five highest startup rates in the country, while Nebraska (6.0 percent), Wisconsin (5.9), Iowa (5.8), West Virginia (5.5), and Vermont (5.3) registered the five lowest.

A growing population naturally carries with it opportunities to launch new enterprises to service new residents. And plentiful consumers, incomes, and workers foster local economic environments conducive to taking the risk of starting a new business. Similar principles hold at the national level too— that a growing population and economy inherently hold more opportunities for entrepreneurship than a shrinking one. Thus, the country’s broader demographic transformation into an older, slower-growing nation with fewer births, fewer immigrants, and fewer prime-age workers suggests that American entrepreneurship will face serious headwinds for decades to come.

More than 75 percent of metro areas saw more businesses close than open in 2019.

Deep into what became a record-long economic expansion, only 90 of the country’s 383 metropolitan areas saw more firms open than close in 2019, leaving more than three-quarters (76.5 percent) in the red. Provo, UT, one of the country’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas and an emerging advanced technology hub, posted the country’s strongest metro area startup rate of 12.1 percent, followed by Las Vegas, Orlando, Boise, and Austin.

The metro areas in which startups exceeded closures were overwhelmingly concentrated in the South and West, regions of the country experiencing rapid population growth. Only eight metro areas in the Northeast and Midwest had more startups than closures, including fast-growing Columbus, OH, and parts of eastern Pennsylvania that are integrating as bedroom communities into the greater Boston-Washington corridor: East Stroudsburg, Lancaster, and Lebanon. Dover, DE; Lewiston-Auburn, ME; and Janesville and Oshkosh, WI, round out the list.

Information and transportation posted the highest startup rates even before the pandemic.

Going into the pandemic, the transportation and warehousing and information sectors registered the highest startup rates in the economy. While the information sector houses the digital heart of the American economy, the transportation sector serves as its lifeblood, leading the integration of the physical and digital realms, serving e-commerce, delivery, and numerous other internet-powered transformations. At the other end of the spectrum, the heavier, capital-intensive manufacturing and utilities sectors registered the lowest startup rates in the economy.

By total number of startups, the industry sectors that produced the most new firms were professional services, construction, and accommodation/food services, which are among the largest sectors by number of firms overall.

Thus official data for 2019 show that American entrepreneurship remained quiescent on the eve of the pandemic. These data paint a picture of a startup ecosystem in the United States that is struggling against economic and demographic headwinds yet still endowed with pockets of dynamism in certain sectors and localities.

There are glimmers of good news in other business formation data covering the pandemic itself. Complementary Census Bureau datasets tracked by EIG looking at new applications to start businesses hint at a subsequent explosion in entrepreneurial activity shortly after the pandemic hit in 2020 (how much out of necessity as people lost jobs and livelihoods or out of genuine opportunity is an open question).

This surge in entrepreneurial intent suggests that the U.S. economy has experienced a once-in-a-generation pro-entrepreneurship shock in recent months. Yet how many of those applications actually get translated into genuine new employer businesses— and then how many of those survive— remains uncertain. Whether the pandemic bump in entrepreneurship proves fleeting or durable is one of the most pressing questions facing the economy today.

These data bookending the pre-pandemic economic expansion sound a note of caution. American economic dynamism across indicators, not only the startup rate, struggled mightily during the 2010s. The pandemic has not changed everything. It has not altered our demographic trajectory; instead it appears to be hastening population decline. It has not clearly produced more competitive markets or weakened incumbent power. It has not redefined the map of access to capital, or changed the rate of knowledge diffusion across the economy. Therefore the data from the Census Bureau’s final Business Dynamics release of the 2010s vouch forcefully for a near-term policy agenda that intentionally makes the most of this moment of entrepreneurial ferment to set the U.S. economy on a more dynamic trajectory.