On Ideals and Innovation

Any sports writer will tell you that a great rivalry makes for a good story. But you also need a good story to make a great rivalry. Only when we have projected our ideals and our fears onto the adversaries, casting them as heroes or villains, do we truly care who wins the game.

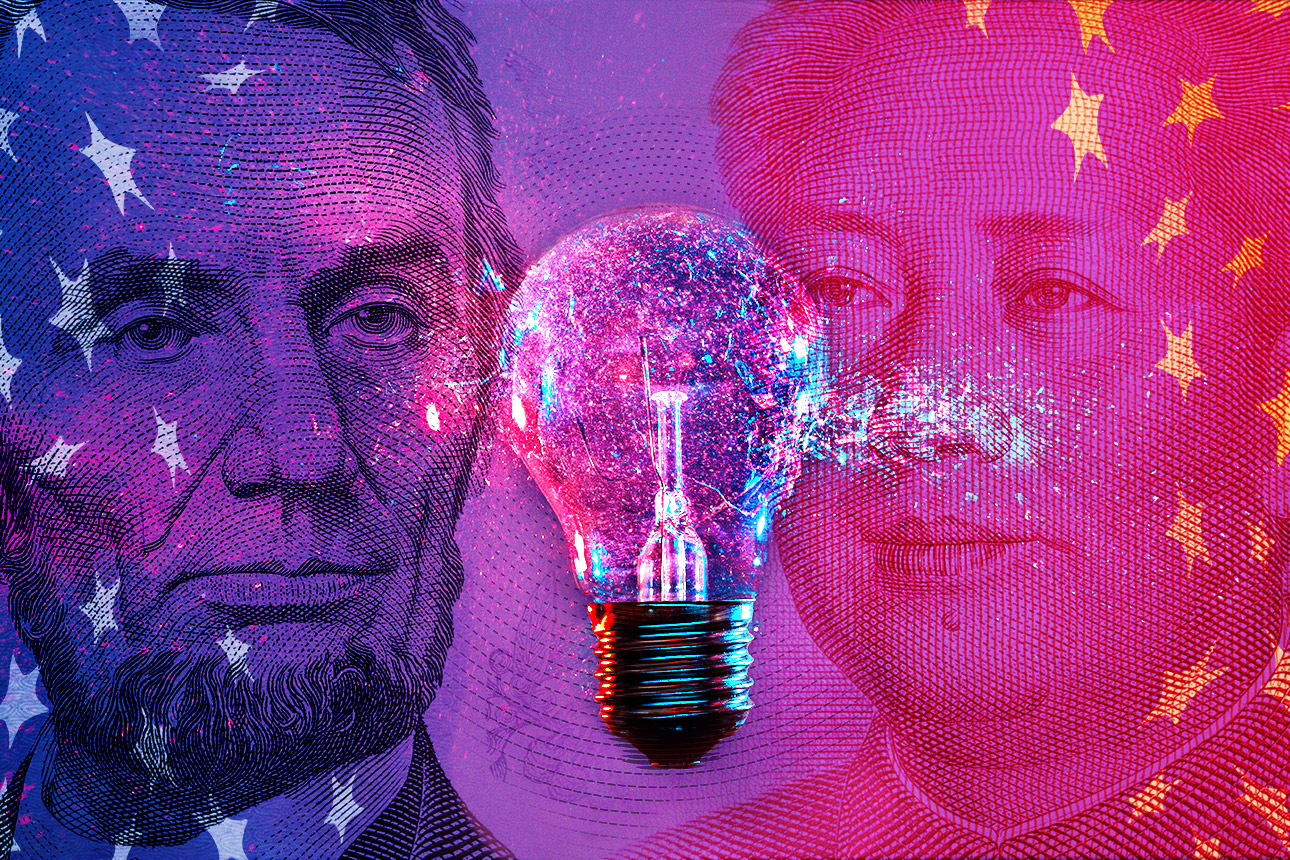

The rivalry between the U.S. and China for economic dominance commands attention because of its massive significance for our own economy, but it also carries a compelling narrative: Each nation is the global standard-bearer for a distinct set of ideals. In this issue, economic historian Carl Benedikt Frey views that rivalry through the lens of culture and discusses how it has influenced the two countries’ comparative advantages. While he leaves aside questions of dueling ideologies, I think there is nonetheless an “idea of America” underlying the essay — an idea that has been under siege since well before Jan. 6, when a mob invaded the U.S. Capitol seeking to accomplish by brute force what it had failed to achieve at the ballot box.

Frey asserts that China’s collectivist culture gives it an advantage in mass production, but he credits the U.S.’s individualistic bent — and its associated characteristics, such as an openness to outsiders, willingness to challenge orthodoxy, and a highly mobile labor pool — with driving innovation and growth. But I would argue that these traits rest on not only individualism but also the optimistic formula underlying the now battered — and unequally distributed — American dream: that our abundance rewards anyone who lands on our shores willing to work, that new ideas advance rather than threaten us, and that there’s always another opportunity if we look for it.

We saw little of this idealism in January. Instead, we witnessed an aggrieved crowd assembled in service of a cynical lie, representing a fearful nation where abundance and opportunity are to be hoarded. Increasingly, rational thought is fended off with the circular logic of conspiracy theories. While the accompanying hostility toward science may be rooted in a backlash against elites, it also rejects the Enlightenment ideals on which this country was founded. We are a body politic in such epistemic crisis that we can’t even agree on what we know to be factually true.

Taking a long-range view of global superpowers’ shifting dynamics, we see China as our rival of the moment. But if we undermine the conditions that have fueled innovation and growth, we will find our greatest adversary in the mirror. And if we abandon the ideals that have welcomed and attracted generations of the brightest thinkers to come create the future with us, we risk losing the game on an own goal.