Pentagon Prototypes 5G With Innovation On-Ramp

SOURCE: National Spectrum Consortium & Advanced Technology International

WASHINGTON: As the Defense Department scrambles to keep ahead of China, it’s relying more and more on public-private partnerships called consortia to connect it to innovative high-tech firms. The latest example comes in an announcement Monday that only members of the National Spectrum Consortium can bid on pilot projects to install prototype 5G networks to manage radar and radio spectrum, “smart warehouse” logistics, and other functions on four military bases.

The consortium’s 260 current members – ranging from universities to start-ups to corporate giants like AT&T and Lockheed Martin – have been working with the Pentagon on 5G at least since January, holding industry days with almost 500 attendees and submitting over 260 white papers to educate officials on the art of the possible. Now the Defense Department, working through Army Contracting Command, has entered into a five-year Section 815 Other Transaction Authority agreement with the Consortium.

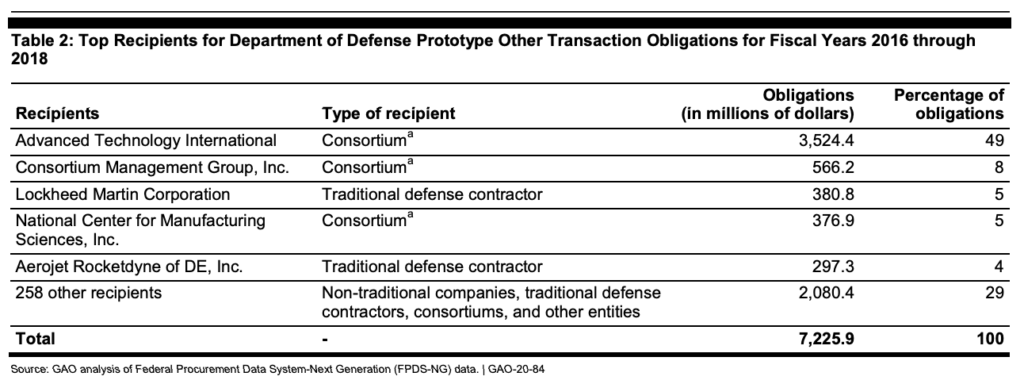

SOURCE: Government Accountability Office

Writ large, over the last three years, as the Pentagon has nearly tripled spending on streamlined Other Transaction Authority (OTA) prototyping contracts, more than half that money has gone to consortium members. Some 49 percent went to consortia administered by a single management contractor, South Carolina-based Advanced Technology International (ATI). And future prospects look good. One group, the Space Enterprise Consortium – run by ATI – may even see its Air Force funding increase 24-fold.

Now, it’s not hard to join these organizations. For your company, university, or nonprofit to join the National Spectrum Consortium, for example, you need to fill out an online form, prove you actually do relevant R&D in the United States, and pay an annual fee of $500. But the self-governing group and its management contractor ATI do play an important role in vetting companies for membership, connecting them to the Pentagon, presenting their proposals and administering contracts. That’s helpful for any company but vital for small firms that can’t hire their own experts in the arcana of defense procurement.

“What’s really unique about it is the collaboration,” said Sal D’Itri, an executive with venture-capital-backed startup Federated Wireless who was elected by the NSC members to serve as consortium chairman. “The Silicon Valley innovator is welcomed in to work with the Department of Defense and its traditional partners, on commercial-like terms.”

Access To ‘NonTraditional Companies

“Using a consortium like this, through an Other Transaction, gives the government access to those nontraditional companies that don’t have somebody around reading FedBizOpps every day,” added consortium vice-chairman Howard “Hojo” Watson, a retired Navy pilot now with IT services company Vectrus. “Mom and pop shops or whoever that have great technology, that DoD maybe would have never known about… now get access to government work.”

Sal D’Itri

Overall, there are 25 Pentagon-sponsored OTA consortia, most of them founded in the last five years, including the National Spectrum Consortium, created with proceeds from a 2015 auction of Defense Department spectrum to the private sector. The granddaddy of them all was created by the Navy and nine shipbuilders in 1998 – and managed ever since by ATI – to shore up an ailing heavy industry in the depths of the post-Cold War drawdown. Since then the consortium model has spread to cutting-edge sectors like aerospace, cyberspace, and outer space. While Other Transaction Authority prototyping funds are still a fraction of overall defense procurement, most of which follows the traditional model, the OTAs are rapidly growing and handling some of the Pentagon’s most important priorities.

“It’s not a new thing, [but] in the last three or four years the number of consortia has grown,” acquisition reform guru Bill Greenwalt told me. “It probably will be more significant in the future if DoD really wants to compete with China…. These types of arrangements are a great way to get the entire industrial base together.”

“Rapid prototyping builds better policy, and that’s really what we’re all about, ” D’Itri told me. “Let’s get these [new technologies] out in the field and start prototyping and testing them.”

On-Ramps, Not Roadblocks

On the current 5G pilot program and others like it, the Pentagon first awards a single Other Transaction Authority contract to a consortium, then selects individual consortium members to receive awards, effectively acting as subcontractors. Is this a good model?

Andrew Hunter

“It can make sense when the purpose of the consortium is to gather together an entire industry to solve a joint problem,” said Andrew Hunter, a former senior acquisition official now with CSIS. “For example, the Vertical Lift Consortium” – also run by ATI – “has allowed DoD to work together with industry to discuss common standards for future vertical lift platforms” – a family of high-speed, long-range aircraft to replace conventional helicopters.

“This approach works well when there are a core group of industry players working on a topic where cooperation is mutually beneficial and in the government’s interest as well,” Hunter told me. “It is more controversial when there isn’t an obvious advantage.”

Greenwalt, who as a Hill staffer wrote much of the current streamlined procurement law, was much more enthusiastic. “This is all about two things: bringing in non-traditionals and using Other Transactions,” he told me. “I have not yet heard of any company complaining that the fees are exorbitant or anything, [and] it’s easier for a non-traditional [company], because you have the consortium managers and the consortium to help you enter the market.”

Bill Greenwalt

Without that kind of help to navigate the bureaucracy, and without the streamlined OTA process, he argued, “small or non-traditional [firms] are just going to walk away.”

How does the Pentagon benefit? “It’s an easier way to access the industrial base, it’s a faster way to get on contract,” he said. “You can be on contract and have these guys doing something within 60 to 90 days.” It’s also harder to protest a consortium OTA award, a process which routinely slows down other contracts.

The one weak point that worries Greenwalt. So far, the Pentagon has used the consortia exclusively for research & development, not actual production of working weapon systems.

Legally and procedurally, he said, it’s entirely possible to move from a prototyping award into production. “They can deliver a directed award Other Transaction or a FAR [Federal Acquisition Regulation] contract based on the competition that’s going on through that consortium,” Greenwalt told me. “So far we haven’t seen any of those transitions yet. It’s all been R&D.”