Pneumatic tubes: technological innovation and politics in “Boss” Shepherd-era Washington DC

To view images full size & high resolution, left click on each

By Matthew B. Gilmore*

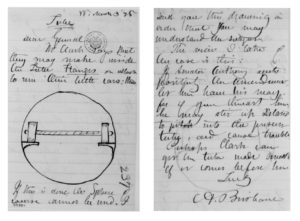

Deep in the archives of the Smithsonian Institution is a folder labeled “Pneumatic tubes” containing just a few curious documents — three letters to Professor Joseph Henry, one from Columbus Delano dated May 16, 1873; a letter from Gen. O.E. Babcock (on Executive Mansion letterhead) dated May 22, 1873; and a letter from Albert Brisbane dated May 25, 1873. Accompanying the three letters is a folded-up prospectus on which has been written “Brisbane’s Pneumatic Tubes.” The actual document title is “New system of transportation by means of hollow spheres, carrying their loads inside and moving in pneumatic tubes.” Herein lies a tale of technology, money, and politics in the era of Alexander (“Boss”) Shepherd Washington.

Detail from Albert Brisbane’s prospectus, “New system of transportation by means of hollow spheres, carrying their loads inside and moving in pneumatic tubes.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, William Jones Rhees Collection.

These correspondents were some of the most prominent men in Washington. Joseph Henry was Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for three decades, from 1846 to 1878; Columbus Delano was Secretary of the Interior from 1870 to 1875; General Orville E. Babcock was Superintendent of Public Buildings from June 1871 to March 1877 and private secretary to President Grant; New Yorker Albert Brisbane was an inventor, a political theoretician, and radical communitarian, and wealthy dilettante. This handful of letters shed light on a small part of the story.

Delano’s letter to Henry announces Henry’s appointment to an investigative committee to be composed of Henry, Babcock, and Almon M. Clapp. Clapp was the Congressional Printer. Congress had just passed a resolution directing Delano to investigate the failure of Brisbane to complete his pneumatic tube project; Delano turned to these three men.

Babcock’s letter was in reply to a (missing) note from Henry. He wrote to Henry agreeing to meeting on the proposed date. But the committee’s charge and plan how it was to proceed seems to have been in question. Babcock wrote:

“. . . we have nothing to do except to report what has been done and why it was suspended. I do not understand that we have anything to do with Mr. Brisbane — except on those points — the Sec’y does not invite us to have anything to do with Mr. Brisbane[‘s] tubes further than to report to the Senate in reply to the resolution.” [1]

Brisbane wrote to Henry proposing that he could switch to a smaller circumference for the tube — 16 inches and change materials to iron (from wood). This would allow the tube to be placed beneath the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s tracks and would now be watertight. [2]

Brisbane described his “new system of transportation by means of hollow spheres, carrying their loads inside and moving in pneumatic tubes” as an “invention which proposed to transport the mails and products of the country . . . to and from all parts of it in a few hours, instead of days, and at a cost far less than by means of railroads.” He proposed the use of “the SPHERE,” hollow spheres filled with cargo of some kind and sent through pneumatic tubes.

In a section titled “Practical Details,” Brisbane suggested that treated wood (boiled in coal tar) would be the best material for tube construction, wrapped with iron hoops at intervals. In this he was (probably) imagining above ground construction. The practicality of pneumatic propulsion was, in Brisbane’s view, enhanced by use of the sphere. A true vacuum would not be needed, only the rush of air.

Detail from Brisbane prospectus. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Rhees Collection.

How it Began

In 1870 Congress passed a resolution expressing interest in pneumatic technology. The potential of employing vacuums for mechanical purposes had been explored in Europe since the 1840s. Atmospheric rail was an early experiment — to propel rolling stock using a vacuum in an attached tube. Soon, inventors experimented with putting the entire train inside the tube. By 1865 pneumatic transport of goods was accomplished in London, reported to American newspaper readers in papers like the Alexandria Gazette on December 9, 1865 when the Gazette reprinted a London Times report on a two-mile dispatch of goods from Holborn to Euston.

December 9, 1865 Alexandria Gazette reprinted of London Times piece on of a two-mile dispatch of goods from Holborn to Euston.

In America, experiments with pneumatic transportation of goods had also been proposed, and in 1868 New York passed “An act to provide for the transmission of letters, packages[,] and merchandize in the Cities of New York and Brooklyn, and across the North and East Rivers, by means of pneumatic tubes, to be constructed beneath the surface of the streets and public places in said cities, and under the water of said rivers.”

This ambitious scheme called for street side receptacles allowing the public to directly deposit letters and packages. The Evening Star had reported two years earlier that a pneumatic tube dispatch company was forming in New York. [3]

In 1870, as reported, the idea began to gain traction in Washington:

“. . . the Committee on Printing having learned, in the spring of 1870, that pneumatic tubes were successfully used in London, Paris, Berlin, and elsewhere for the prompt transmission of messages, letters, and parcels, thought that such a mode of conveyance between the Capitol and the Government Printing-Office would be of great practical benefit, for the speedy transmission of proofs, bills, and reports, and would materially aid legislation. The Senate, on the 15th of July, 1870, directed the committee to inquire into the subject, and the result of their correspondence with both practical and scientific men confirmed them in the opinion that a small air-tight cast-iron tube might be successfully and profitably used.” [4]

Discussions of pneumatic tubes were not taken entirely seriously in the Washington press. The February 5, 1872 National Republican newspaper was clearly spoofing the idea when it described a pneumatic tube to convey congressmen from an entrance at the bottom of Capitol Hill at Pennsylvania Avenue, squirting them directly into their seats on the Senate or House floor. [5]

A few months later, on May 6, 1872, Congressman James A. Garfield’s introduced A Bill Relating to the construction of a pneumatic tube from the Government Printing Office to the Capitol to appropriate just $15,000 for construction along the seven-block route contained the following:

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the sum of fifteen thousand dollars be appropriated for the purpose of constructing a pneumatic tube, upon the plan invented and patented by Albert Brisbane, of the city of New York, June twenty-second, eighteen hundred and sixty-nine, from the Government Printing Office to the Capitol, to be expended under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, and the work to be done under the supervision of the Architect of the Capitol Extension.”

This effort failed, but modified language was incorporated into the May 24, 1872 Act making appropriations for sundry civil expenses of the Government for the fiscal year ending June thirtieth, eighteen hundred and seventy-three, and for other purposes:

“That the sum of fifteen thousand dollars be appropriated for the purpose of constructing a pneumatic tube, upon the plan invented by Albert Brisbane, from the Capitol, along North Capitol street, to the Government Printing Office, for the transmission of books, packages, etc., to be expended under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, and the work to be done under the supervision of the Architect of the Capitol Extension.”

The prescription of using Brisbane’s invention in the legislation was debated and while attempts were made to strike it out but proved ultimately unsuccessful. [6]

Excerpt from the Congressional Globe of June 7, 1872, p. 4396-7.

Garfield’s role in getting the appropriation for Brisbane was public knowledge. The June 17, 1872 New York World announced it; newspapers as far afield as the Waterloo, Iowa Courier on August 15th, as well as others carried these press reports.

Brisbane’s Pneumatic Tube

Brisbane had many (chimerical) ideas — but what had he proposed for Washington? His pneumatic tube was to be 32 inches in diameter, composed of treated wood strips bound with iron bands. The carrying device inside would be spherical. In an October 10, 1872 letter to Garfield, Brisbane wrote that his tube builder could construct (or complete) the tube in 20 days with 12 men; that turned out to be a wildly wrong estimate.

Two weeks later, on December 2nd, the Evening Star reported that construction on the tube would be completed by July 1, 1873. The next day, December 3rd, the Star reported that Brisbane had been given permission for the trenching necessary along North Capitol Street.

The previous year, on November 15, 1872, the Evening Star had published a long front page interview with Brisbane describing his plan and the project itself — and his much more grandiose goals for cross-continental pneumatic transport — even as discussions were just beginning about proposals to extend the system to executive departments. [7]

October 10, 1872 letter from Brisbane to Garfield. James A. Garfield Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Div.

Buoyed by the (potential) success of the Capitol/Printing Office pneumatic tube, on December 11th the Alexandria Gazette reported that a bill was introduced for “the construction of a pneumatic tube road from New York to New Orleans. . . .” And the Father Abraham newspaper of Lancaster City, Pennsylvania reported that the pneumatic system could send packages from New York to San Francisco. (By 1887 J.H. Pearce of Southington, Connecticut suggested a “Pneumatic tube to Europe” across the Atlantic). [8]

Underground construction is complicated, as Brisbane soon found. An article in the National Republican of February 10, 1873 headlined “Carelessness; The Capitol deprived of spring water to-day” described the construction accident which broke the pipe delivering water from Smith Farm to the Capitol. Workers on the pneumatic tube somehow broke the water pipe, which then flooded the pneumatic tube. The Star of the same day was more generous and didn’t ascribe the accident to carelessness.

Map by author of Brisbane’s pneumatic tube plan.

Albert Brisbane

Brisbane was an exceptional man, a wealthy dilettante interested in technological and political innovation. His correspondence with Garfield consists of a mixture of details of the progress (hoped for and actual) on his pneumatic tube project and injunctions for Garfield to prepare for and be a leader in the coming political revolution. He was a devotee of Charles Fourier, the French utopian socialist. (Fourier had described a plan for small socialist communities called phalanxes. Twenty-eight were created in the United States, but none lasted more than only a few years.)

In 1840 Brisbane published a socialist and communitarian, Fourier-derived work titled Social Destiny of Man. [9] He converted founder and editor of the New York Tribune Horace Greeley to his cause, and Greeley gave Brisbane a column in his newspaper. [10] Brisbane remained optimistic of political revolution throughout his life, as is evident by his correspondence with Garfield. He doubtless saw the promise of pneumatic technology to change the relation of man to work as a component of his social philosophy; he wrote to his French Fourierist colleague Victor Prosper Considérant about his pneumatic tube invention and project.

Brisbane and Garfield corresponded throughout the 1870s; letters from him to Garfield date from May 24, July 17, August 5, and October 5, 1872. In addition to the business of the pneumatic tube, Brisbane wrote to Garfield of his political ideals; on July 17, 1872, he wrote of the coming “industrial republic” and his hopes that Garfield would be a part of the movement. On June 27, 1873 Brisbane advised Garfield to “[r]ead Fourier. You will see a new world. There is coming a revolution in Politics. Stand by to be a leading person.” [11]

Congressman Garfield

There’s no indication of how Garfield and Brisbane became acquainted. Garfield’s diaries offer up an interesting timeline: On May 17, 1872 Brisbane presented his pneumatic tube scheme to the committee; Garfield noted, “We run some risk of being laughed out of the House, but remembering the example of the appropriation for Morse, I shall take the risk, believing this will develop into a great invention.” On May 23rd he noted that he got the Brisbane project into the Sundry Civil Bill. On the 25th he visited Brisbane in the evening. By June the project seemed to be going well, and on the 19th he noted that he “[l]unched . . . with Brisbane. Pneumatic tube progresses favorably” [12]

A few months later, on November 9th, Garfield noted in his diary, “Visited Brisbane in the evening and heard his account of his acquaintance with Fourier, of whom he is evidently a worshiper.” Later that month, on the 20th, he called on Brisbane “. . . and discussed the prospects of the Pneumatic Tube.” A nearly identical notation appears on December 6th. Late in December, as wryly noted by Garfield, Brisbane fell asleep a presentation Garfield in Montana on the 28th. Four days later, New Year’s Day 1873, Garfield had dinner with Brisbane and “two ladies.” By May the subject seems to have shifted perhaps; on May 18th Garfield noted, “Had an interesting visit with A. Brisbane in the evening. He is a genius.” But by then Garfield’s perspective on Brisbane took on more nuance:

“In the evening dined with Albert Brisbane, and heard him talk of Fourier, and the social philosophy. B is a wonderful man, full of genius and eccentricity. Much that he says of social philosophy comes within the circle of my own experience. . . . I hope Brisbane will come down to the earth and finish his tube. [20th]

“Read Fourier on monopoly, acreage, and joint-stock corporations. His writing of 1808 sounds like prophecy fulfilled. Mr. Brisbane called and gave us a talk on his social philosophy, particularly his doctrine on currency. . . . Brisbane is as impractical as possible, but very brilliant. He wants to convert me to his theory of the currency, and have me take charge of what he calls the ‘great movement.’ Says Butler will do it if I don’t.” [24th]

Notwithstanding his ambivalence about Brisbane’s enthusiasm for Fourier, on July 2nd Garfield was citing the French utopian in his address, “The Future of the Republic: Its dangers and its hopes,” given at Western Reserve College in Ohio.

Brisbane appears again in Garfield’s diary in a November 22, 1873: “Albert Brisbane took dinner with us and instructed Crete in his theory of cooking oysters. . . . . After dinner spent the evening listening to Brisbane’s theory of socialism and life.”

Finally, on June 16, 1874 the pneumatic tube resurfaced in Congress and Brisbane testified before the committee. [13]

Investigation

In March 1873 the Senate expressed its concern that “. . . the pneumatic tube . . . connect[ing] the Capitol with the Government Printing-Office has not been completed. . . .” This is both curious and confusing since the deadline was not for another three months — June 30th — but it was soon after the construction accidents.

Excerpt from letter of the Secretary of the Interior, communicating in answer to Senate resolution of March 26, 1873, information relative to the pneumatic tube.

Evening Star, June 7, 1873.

The three-man committee found in its investigation that the issue preventing timely completion of the tube was simply the construction difficulties encountered — heavy soil and underground streams, exacerbated by the increased diameter of the tube. The committee wanted to see the tube completed (if it required no further appropriations). Brisbane did offer to complete it with his own funds. Delano was unsympathetic and brusquely denied his request for an extension of time.

Epilogue

While unenthusiastic about continuing with Brisbane, the Senate was not yet willing to abandon the pneumatic tube project entirely. In 1875 Senator Henry Anthony of Rhode Island submitted a report on the debacle by which “The committee recommend that provision for the construction of such a tube be inserted as an amendment to the bill (H.R. 4729) making appropriations for sundry civil expenses of the Government for the next fiscal year, and they believe that it will promote the perfection, the celerity, and the economy of the public printing.” [14]

They had solicited information on the history and feasibility of the technology from Englishman Benjamin C. Pole who gave a positive report, thereby encouraging the committee to push for funding of a non-Brisbane solution. Despite his encouraging assessment the project seems to have died in Congress. Pole was another engineer and eccentric inventor and street railroad promoter. His East Deanewood streetcar scheme went nowhere, but he built the engines powering the Glen Echo Trolley line. [15]

Brisbane was still hopeful, and on March 3, 1875 he wrote to Garfield with another plan which abandoned the sphere (and also offered more advice).

March 3, 1875 letter from Brisbane to Garfield. James A. Garfield Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

Brisbane was nothing if not persistent, and on October 26, 1880, he wrote to Garfield, with yet another new tube scheme. As the presidential campaign was drawing to its conclusion, Brisbane expressed his confidence Garfield would win. In an historically ironic postscript, he wrote, “I do not ask you to appoint me Consul at Paris, but I wish you would entrust me with negotiating a Commercial Treaty with France.” In 1887 Z.L. White, Washington correspondent for Science, headlined his (very unsympathetic) profile of Brisbane “A sketch of a noted crank.” [16]

The New Century

The May 10, 1890 Evening Star reported “Pneumatic Possibilities; Mr. Wanamaker thinks of introducing tubes in the postal system.” The well-informed reporter even included two paragraphs on the Brisbane tube attempt and its failure. Wanamaker’s department store in Philadelphia had used pneumatic tubes to ferry cash since 1880, replacing the cash boys and cash girls.

As U.S. Postmaster General in 1892, John Wanamaker did implement a pneumatic postal mail<https://hiddencityphila.org/2014/04/pneumatic-philadelphia> system in Philadelphia; it was inaugurated the following year. The Post Office expanded the pneumatic tube technology in Philadelphia, New York, Chicago, St. Louis, and Boston. [17]

The idea for implementing pneumatic tube technology in Washington still held an allure and bubbled up periodically. Late in 1899, the Washington Times edition of November 11th reported that Second Assistant Postmaster General William Shallenberger sought to expand the post office’s pneumatic mail system to Washington. A few months later in 1900 the March 13th Evening Star reported that the District Commissioners would take an agnostic approach to legislation for (of all things) a pneumatic tube from the Capitol to the General post Office because they were “unaware of the desires of the authorities [GPO and the Congress].” [18]

In 1914 R.G. Collins, representing the United States Pneumatic Co. of New York, in testimony before the Commission to Investigate the Pneumatic-tube Postal System, stated, “I do not think there can be any question but that [the] tube system which will carry 99½ per cent of all the packages, and carry all the mail of course, and everything of that kind between the different buildings, will furnish a means of carrying on this service, which is a very essential part of the Government service, with much greater speed and rapidity and be a very great convenience in transacting the Government business.” [19]

The system proposed contemplated 30-inch tubes, much larger than the existing eight-inch systems. To be connected were the Government Printing Office, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Station F of the Washington city post office and existing and new post offices, the Capitol and Senate and House Office Buildings, the Census Bureau, Agricultural Department seed, and the Municipal Building. Also to be included were to be the Treasury, State, War, Navy, and Commerce, Justice departments, as well as the Court of Claims, Geological Survey, Pension Bureau, and Patent Office — for a total of 9.4 miles.

“A direct tube between the Government Printing Office and the Capitol Building” was suggested, at a cost of $50,000 to $75,000 – three to five times the cost of Brisbane’s attempt over 40 years earlier. [20]

In 1904 further extensions (or introduction) of pneumatic postal service was studied for seventeen major cities, including Washington. For Washington the uncertainty of plans for Union Station and nearby postal facilities led to deferring consideration. [21]

A demonstration system had been “installed between the Capitol and the House of Representatives Office Building. This is known as the Burton system. It consists of an 18-inch tube and two terminals, and is the only pneumatic tube constructed, as far as I have been able to learn, having a diameter greater than 10 inches. It was installed in the summer of 1911, put in condition for use In September of that year, and has been operated intermittently for the purposes of demonstration only. I observed its operation on November 12, 1913.” [22]

As late as 1944 Congress passed an “Act to permit the construction and use of certain pipe lines for pneumatic tube transmission in the District of Columbia — to lay down, construct, maintain, and use not more than three pipe lines for a pneumatic tube system from a point within said lot 81, square 50, through connecting public alleys, across Twenty-third Street Northwest, through a connecting alley to a point within said lot 10, square 36” which authorized the Bureau of National Affairs to construct pneumatic tubes under 23rd St NW in the West End.

Today, pneumatic technology has a slightly risible air, with pneumatic tubes associated in popular imagination with their key role in Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film, Brazil. Few know that in Washington an attempt was made to be at the leading edge of pneumatic technological innovation, or that a utopian socialist inventor/philosopher instigated it. But in the day, this ultimate in analog technology was seen as a likely competitor with the telegraph (as Garfield’s note makes clear). Washington never got its federal pneumatic tubes, not for lack interest, but seemingly for lack of demand and failure of political and bureaucratic will.

Acknowledgements

Tad Bennicoff and all the reference staff at the Smithsonian Institution Archives; Betty Koed and Mary Baumann of the U.S. Senate Historical Office, staff of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Footnotes

Available by clicking here.

<***>

References and Resources

See resource list published on author’s Washington DC History blog.

<***>

*Matthew B. Gilmore is the editor of the H-DC discussion list and blogs on Washington history and related subjects at . Previously, he was a reference librarian at the Washingtoniana Division of the DC Public Library for a number of years. He has presented numerous workshops and public lectures, and published articles and books on Washington D.C. history.