Study: Researchers Find Employed Physicians More Likely to Order Common MRIs | Healthcare Innovation

Could the employment of physicians actually increase the rate of inappropriate diagnostic imaging orders? While the idea might seem counterintuitive to some, a team of researchers has just published a study in the May issue of Health Affairs that points to the conclusion that, yes, employed primary care physicians are ordering more imaging studies.

The title of the article, “Hospital Employment Of Physicians In Massachusetts Is Associated With Inappropriate Diagnostic Imaging,” by Gary J. Young, E. David Zepeda, Stephen Flaherty, and Ngoc Thai, conveys the core finding of the study, which is that, “[T]he odds of a patient receiving an MRI referral increased by more than 30 percent after a physician transitioned to hospital employment (OR: 1.34),” and that, “In terms of marginal effects, when the physician was hospital employed, the percentage change in a patient’s probability of an MRI referral increased by approximately 31 percent for the study cohort and by approximately 29 percent with the comparison group included.”

Early on in the article, the researchers note that “The impact of hospital employment on physicians’ clinical behavior is not well established theoretically or empirically. Although hospitals are legally constrained from paying physicians directly for imaging referrals, they potentially influence employed physicians’ referral decisions through various forms of managerial policies and controls. Previous research suggests that hospitals do exert influence over employed physicians’ referral decisions through policies that require or otherwise encourage them to refer to in-house rather than outside providers.18 Such influence may extend to increasing physicians’ referrals for hospital-based tests and services. For example, hospitals may direct employed physicians to order imaging tests for patients with selected clinical conditions as part of in-house referrals to specialists for further evaluation.”

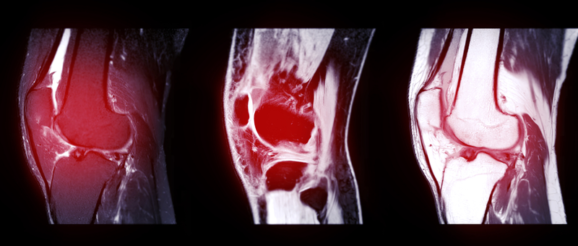

What’s more, they write in the article that “We focused on three common clinical conditions: uncomplicated lower back pain, nontraumatic knee pain without joint effusion, and nontraumatic shoulder pain without joint effusion. We selected these conditions for several reasons: They are prevalent among adults in the US, well-established guidelines exist for when imaging is appropriate, and imaging for the conditions is routinely performed in a variety of clinical settings.13,15 Thus, MRI referrals for these conditions are potentially valuable as tracers for broader changes in clinical practice that may be connected to the hospital employment of physicians. For the study sample, we excluded patients who had chronic comorbidities as well as clinical complications (for example, spinal stenosis) that might affect how a physician assesses the value of an MRI for diagnostic purposes. Patients included in the study sample thus were likely to be generally healthy outside of the relevant condition for which they sought medical care. We also excluded patients younger than age eighteen.”

As the authors note, “Organizational independence between hospitals and physicians has long been a defining feature of the US health care system but also arguably an impediment to better coordination of care for patients. At the same time, the growing trend among physicians toward hospital-based employment arrangements has raised concerns about possible negative effects on the cost, quality, and accessibility of patient care.” Indeed, according to the findings of their analysis, “Once employed by a hospital, physicians were more inclined to refer patients for MRI scans than before their employment.” Looking at MRI scan orders for uncomplicated lower back pain, nontraumatic knee pain without joint effusion, and nontraumatic shoulder pain without joint effusion, they found that “hospital employment was associated with a substantially greater likelihood of patients receiving MRI referrals in general, as well as—more important—inappropriate referrals. Once employed by a hospital, physicians were more inclined to refer patients for MRI scans than before their employment. Most of the patients that the hospital-employed physicians referred for MRI scans received those scans at the same hospital that employed the referring physician. Our findings offer evidence that such higher costs are not largely a matter of better service access for patients. Our findings are in line with previous studies that have reported an association between hospital-physician integration and higher costs for patient care,” they write. “However, our findings offer evidence that such higher costs are not largely a matter of better service access for patients. Rather, hospital-physician integration appears to be a potential driver of low-value care.”

Digging even deeper, they write that, “As noted, previous studies have demonstrated relatively high rates of inappropriate MRI referrals, which has been attributed in part to a lack of awareness of imaging guidelines among referring physicians. However, as our study accounted for physicians’ MRI referral patterns before hospital employment, such lack of awareness is not a pertinent explanation for the study’s findings. Hospitals potentially influence employed physicians’ referral decisions in several ways, including by directing physicians to order certain tests in connection with patient referrals for additional, in-house care. Whether and to what extent hospitals exert such influence for MRI referrals is unclear, but certainly a financial incentive exists to do so, as MRI scans have long been an important source of revenue for these institutions. Imaging services have been estimated to account for more than 30 percent of hospitals’ profits, and MRI scans specifically constitute a large portion of the high-margin imaging services that hospitals deliver. At the same time, it is also possible that physicians, once embedded in a hospital environment through an employment arrangement, become more inclined to refer patients for MRI scans, including those that do not strictly meet appropriateness criteria, because their employment arrangement facilitates such referrals.”

And while they themselves state that “[O]ur study results do not resolve the debate over whether greater hospital-physician integration is a positive development for the US health care system,” they state that “Our own study indicates an association between hospital-physician integration and inappropriate imaging. However, although this finding is in line with previous research reporting an association between such integration and higher costs for patient care, it is the first such investigation, to our knowledge, to specifically examine integration relative to low-value care; thus, more evidence is needed before firm conclusions can be reached.”

Indeed, they conclude that, “As the effects of hospital-physician integration on patient care become better understood, policy makers may consider using payment and regulatory mechanisms to either promote or impede the shift in physician services from physician-owned to hospital-based practices. Most recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services revised its reimbursement approach for physician services to reduce the long-standing payment differential favoring hospital outpatient settings over physician-owned practices, which itself has provided an incentive for hospitals to invest in physician services. Additional policy initiatives of this type may occur in the future as the debate over hospital employment of physicians moves forward,” they write. “Accordingly, we are hopeful that additional research will be undertaken to assess the advantages and disadvantages of physician employment for the US health care system.”

Gary J. Young is director of the Center for Health Policy and Healthcare Research and a professor at the D’Amore-McKim School of Business and Bouve College of Health Sciences, Northeastern University, in Boston, Massachusetts. E. David Zepeda is an associate professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, in Boston, Massachusetts. Stephen Flaherty is a data scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, in Boston, Massachusetts, and an assistant professor, Meehan School of Business, Stonehill College, in Easton, Massachusetts. Ngoc Thai is a Ph.D. student in population health, Bouve College of Health Sciences, Northeastern University.