Tech’s innovation boom may have been bad for the economy | Fortune

Giants such as Facebook, Amazon, and Google have become some of the wealthiest corporations in history, seen by many as indestructible money-making machines. Even as the nation struggled through a “jobless recovery” after the Great Recession of 2008, Big Tech was the Ayn Randian sector proving America had the best of all capitalisms. Technology has been criticized for harming American democracy, youth mental health, and even contributing to long-term economic stagnation. But the sector argued that its innovation made it exceptional enough to operate in its own quasi-libertarian golden state — that regulatory burdens shouldn’t apply, and that its geniuses should be free to work without hurdles. They pointed to the FAANGs outperforming the S&P 500 as proof.

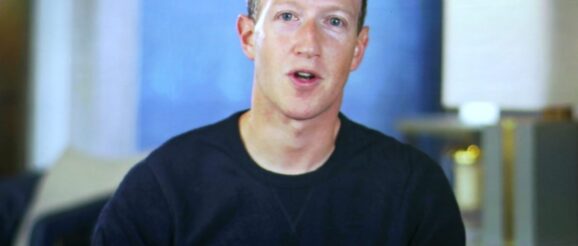

For a time, things seemed to work. Buoyed by over a decade of near-zero interest rates, capital was seemingly everywhere in tech. Then the early pandemic sent tech stocks soaring even higher. But that party ended a year ago, when Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta empire suffered the largest single-day drop of any publicly traded company in American history. Big tech firms have since become exceptional in all the bad ways: the rest of the once-mighty FAANG companies seeing record drops in market cap; and tech giants laying off thousands upon thousands of workers, even as the rest of the economy grows. Meanwhile the ultimate risk and innovation asset, cryptocurrencies, have lost roughly two-thirds of their value, as crypto’s “market cap” shrank from $3 trillion to roughly $1 trillion in a year marked by several huge meltdowns.

The notion, too, that the big brains of the innovators in our startup economy are truly exceptional took a beating last week, when the “thought leaders” that populate the venture capital industry fell victim to the most old-fashioned kind of financial panic. The blow-up of Silicon Valley Bank has been blamed on lax regulation by the Federal Reserve, rules weakened by a feckless Trump-era Congress, mismanagement by bank executives, and even, bizarrely, on “wokeness” or too much remote working. SVB was not a normal bank, and its relatively unstable depositor base rendered it uniquely vulnerable, as Nobel laureate Douglas Diamond recently told Fortune’s Shawn Tully. But the fact remains: The panicked denizens of that shiny valley tried to withdraw $42 billion in one day. As a joke paraphrasing Zuckerberg that was going around last week put it: The tech industry moved so fast it broke its own bank.

It was clear long before the collapse of SVB that there has been a financial regime change — from the “everything bubble” of the easy money era to an unprecedented global tightening of monetary policy. Perhaps now, amid this sober reappraisal, is the moment to question the magical thinking about risk that was rampant in the era of tech exceptionalism, and to extract it from the mainstream of American innovation.

W(h)ither innovation?

The idea of tech exceptionalism is grounded in what the author Sebastian Mallaby called “the power law,” the belief that investors and inventors could lose on 100 ventures as long as they succeed on the 101st — or as Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg put it in 2016, the willingness to “choose hope over fear.”

That philosophy fueled many risky bets on unprofitable tech stocks, misguided startups, and directionless cryptocurrencies, as the era of cheap money meant investors were comfortable gambling on increasingly absurd ventures, from Theranos to the Juicero to WeWork. The detritus of this irrational era includes thousands of “zombie” companies and cryptocurrencies, companies that are no longer economically viable but have somehow managed to stay alive by taking on more and more debt. And this era left us with various other costs to calculate, including that of what Shosanna Zuboff has called “surveillance capitalism,” as smartphones and social media invade ever more of people’s time.

“Innovation at all costs is never a long-term strategy,” Robert E. Siegel, a lecturer in management at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and a venture capitalist himself, told Fortune. “That’s a strategy in a moment in time when capital is cheap and there’s frothiness in the market… SVB’s implosion is a punctuation mark at the end of a supercycle of low interest rates where capital was chasing returns, and where there was so much money flowed into high-risk high-return assets like venture and startups.”

The check came due last year with steep interest rate hikes to fight inflation which came down on tech like a hammer. Major companies including Meta, Amazon, and Apple all lost hundreds of billions in market cap last year, while venture capital spending dropped 31%.

‘Fewer stupid ventures’

Despite tech’s self-harming lavishness of the past few years, innovation isn’t necessarily dead in the U.S. It can’t be, as the country gears up for big competition from China on everything from A.I. to climate tech. But the type of innovation practiced by the tech industry will have to operate very differently if it wants to survive. That will likely mean putting to bed once and for all the idea of tech exceptionalism.

Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg has called 2023 the “year of efficiency,” while Amazon, Google, and other tech companies are furiously chopping unnecessary departments and projects — including the Quixotic moonshot projects employees once clamored to work on, with little thought of return on investment.

This pivot to efficiency makes sense in preparation for a possible recession. It might also be the pruning that America’s innovation sector needs to stay alive, said Stanford University’s Siegel. “We’re going to see fewer stupid ventures,” he told Fortune. “You’re going to see this because there’s going to be less money to go around. Fewer bad ideas will get funded and there will be less excess.”

Tech probably won’t have to figure out how to innovate more efficiently alone either, as it has invited DC to come in and sort out the mess. It remains to be seen whether Congress or the Federal Reserve are up to the task of overhauling regulation.

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” Charlie O’Donnell, a partner at the New York-based venture capital firm Brooklyn Bridge Ventures, told Fortune. Around a third of the approximately 70 companies in O’Donnell’s portfolio were exposed to SVB’s collapse, and he said he welcomes some thoughtful oversight of the VC world: “At the end of the day, you just want to know what the rules are,” he said. “You just want stability.”

This all means that tech cannot return to its freewheeling ways anytime soon, but the sector can learn from the past year’s trauma. Despite the challenges ahead, innovation in the U.S. is far from dead. It’s time to adapt.