Tenth Law. The interface is the place of innovation

Tenth Law of the Interface: The interface is the place of innovation

What is a designer? How many professional profiles exist within the world of design? Let’s check Wikipedia: clothing and textile designer, fashion designer, jewelry designer, landscape designer, graphic designer, industrial designer, interior designer, multimedia designer, video game designer, audiovisual designer… We could also add interaction designer, web designer, mobile application designer and, last but not least, the designer of interfaces. It seems that almost all professions fall into the field of design.

The interface designer

If the designer seems to be a transversal and omnipresent figure, What is an interface designer? A professional who sketches interactive elements and action sequences on paper? Or an expert in the creation of icons for interactive screens? An international star that models lemon squeezers? Or a gourmet who invents new combinations and techniques in a kitchen- laboratory? If we develop this reflection further, a new conception emerges: the interface designer as an expert in the construction of spaces for interaction between human and technological actors. If every interface hides a set of possible developments or evolutionary paths, the designer is responsible for detecting them and promoting interactions with other actors and interfaces.

The interface designer is not only concerned with the creation of an interface for a software or website, or the design of an application for mobile devices. An engineer is also an interface designer who masters different technologies, skills and knowledge to build, for example, a bridge or a spaceship; similarly, a film director puts a series of technologies and professionals (actors, photographers, editors, writers, audiences, critics, etc.) at the service of an audiovisual narrative. An inventor, a gourmet or an entrepreneur are all interface designers because their function is to create a place for the interaction of human and technological actors. The same can be said of a transmedia producer: this figure, responsible for designing and implementing a communication strategy in different media and collaborative platforms, is for all intents and purposes a designer of narrative worlds. Or, in other words, the transmedia producer is a designer of narrative interfaces that link texts, characters, plots, audiences, fan clubs, media and languages.

At this point we must avoid a temptation: to consider the interface designer a genius who builds a network of actors and controls it from an external position. This is nothing more than an optical illusion: the designer is part of that network and is involved, like any other actor, in its tensions, complexities and conflicts (Secondand Ninth Law).

Radical innovation vs. incremental innovation

Researchers from various disciplines have proposed categories for describing and classifying the different innovation strategies. For example James Fleck (2000) identified twelve modes of technological innovation: mutation, simplification, integration, elaboration, standardization, incrementation, crystallization, configuration, innofusion (innovation during diffusion), resolution, cross-fertilization and implementation. Other researchers, such as Koen Frenken (2006), have proposed models inspired by the theory of complexity (Eighth Law). Sometimes the evolution of an interface is expressed in great changes that transform at the same time all systems and subsystems (radical innovation), while on other occasions the change only moves forward by small steps (incremental innovation).

Regarding radical innovation, in the middle of the 19th century, gas was the most popular lighting system in the main European and American cities. A series of technologies developed at the end of the century (fluorescent, electric or incandescent lamps made of carbon wire, transformers, power plants, etc.) and the adoption of a new standard (alternate current instead of direct current) led to the advent of the electric lighting system. The conflict known as the “war of the currents”, sometimes reduced to a personal dispute between Thomas A. Edison and George Westinghouse, also involved political, scientific and economic actors. The successful recombination of actors in a novel interface implied a radical transformation of the lighting system and the consolidation of a new paradigm based on a network of power plants that produced alternate current, distribution lines, transformers and incandescent lamps.

If we analyze the mutations of the media ecosystem since the arrival of the World Wide Web, the development of participatory environments such as blogs or Wikipedia and the explosion of platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, pram, Netflix or Twitter, we cannot stop ourselves from thinking about a radical innovation process. The so-called web 2.0 or collaborative web is something more than a set of innovative technologies: it is a brand new configuration of the relationships of human and technological actors that generates a new interface.

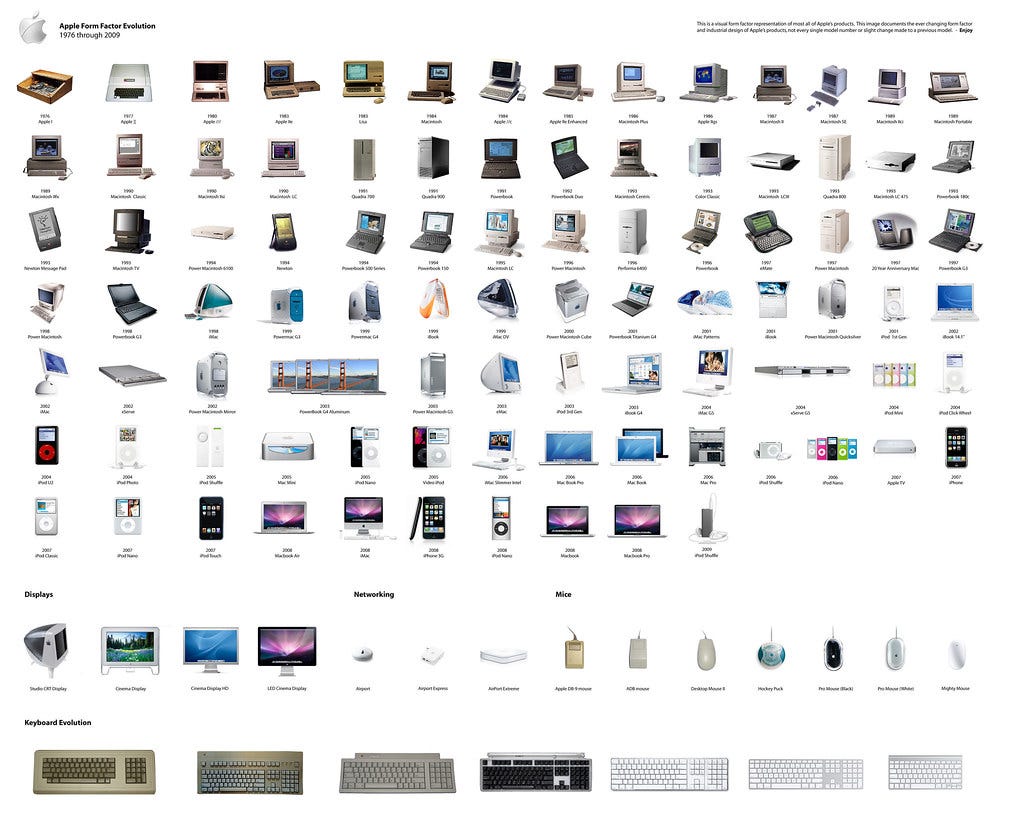

The incremental innovation strategy may be found in different domains and processes. Let’s look at the evolution of Personal Computers. The appearance of the IBM PC and the Apple Macintosh in the early 1980s popularized a new interface for human-computer interaction that included graphical user interface, a hard disk, a processing unit, a screen and a series of input/output devices. In the 1990s this interface did not go through deep changes: microprocessors were faster, screens increased their definition and hard disks expanded their capacity, but the PC paradigm did not change at all. The same is now occurring with smartphones after the arrival of the iPhone: devices are faster, their cameras take incredible pictures and the memory is constantly expanding, but the basic model does not change. The evolutions of the PC in the 1990s and smartphones in the 2010s are both good examples of an incremental innovation strategy.

The limits of the interface

When an interface approaches its limits, it is more difficult to introduce incremental changes by actor addition or substitution. For example, in the 1950s the transistor replaced the vacuum tube when that technology had almost exhausted all its possibilities. When the transistor arrived at the same situation, the microprocessor replaced it at the end of the 1960s. The diminishing returns from a technology trigger the search for innovation. Once it reaches a point in its evolution, the interface has nothing more to say or do (Frenken 2006).

Radical or incremental processes are just a limited sample of the typologies of technological change (we can also find other types like architectural or systemic innovation, modular or component innovation, etc.). Nothing guarantees that one is better than the other or that one of them will be successful. In all cases we must always take into account one element: the users’ tactics. As we saw, all the designer’s strategies are negotiated, criticized and reinterpreted by the users within the interface (Secondand NinthLaw). In the battle of the interfaces, nobody will have the last word.

Note: This text is a synthesis of my book Las Leyes de la Interfazpublished by Gedisa in 2018.

Previous > Ninth Law of the Interface: interfaces are political.

References

Frenken, K. (2006). Innovation, Evolution and Complexity Theory. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Fleck, J. (2000). Artefact ↔ activity. The coevolution of artefacts, knowledge and organization in technological innovation. In: J. Ziman (ed.) (ed.) Technological Innovation as an Evolutionary Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 264.

Tenth Law. The interface is the place of innovation was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.