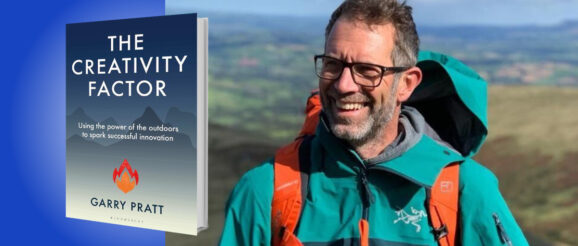

The Creativity Factor: Using the Power of the Outdoors to Spark Successful Innovation

Garry Pratt is the co-founder of Earswitch, a sensor technology start-up. He was previously Entrepreneur in Residence and a Teaching Fellow in Entrepreneurship at the University of Bath. He is also the co-founder of the Outside/community and Walking Leaders, where he serves as a mentor, facilitator, and guide on walking expeditions.

Below, Garry shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Creativity Factor: Using the Power of the Outdoors to Spark Successful Innovation. Listen to the audio version—read by Garry himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. To be innovative or entrepreneurial is to be creative.

The future of the world will be reliant on creativity. Creativity is the life blood of the future, the oil for industries to come. Radical innovation rarely comes from people set in their ways, who simply know more, or have more information, but from those who manage to generate alternative perspectives.

As far back as the 1970s, English economist George Shackle was developing rigorous theoretical frameworks on the nature of the entrepreneurial process. The idea being that business planning and innovation cannot be focused on actual, concrete knowledge of the future, but instead only on one’s imagination of it.

As the future is unknowable, entrepreneurs, managers and workers cannot act solely by identifying optimal choices based on past statistical information. Instead, they need to create and use imagined futures to attend to questions of possibility. The key to this is the acceptance that imagination can be a conscious, unconscious, self-reflective and an embodied process. It’s not just dreaming or thinking. In action, imagination should involve things like sketching, building, playing, having conversations and making connections in the real, physical world.

The results of a 2012 study by Benjamin Baird were striking. Three groups were tested for creativity in three different settings. There was a 40 percent improvement in creative problem solving and idea incubation in the group engaged in an undemanding task, simply resting or taking a break, over those who were doing a demanding task. This may seem surprising, but Baird and colleagues argue that, with no distraction, our thoughts tend to revert to a logical, sequential pattern basis. If our brains are challenged with a complex task, there simply isn’t scope for creativity. Being actively distracted is the sweet spot for creativity to flourish, and it’s not a marginal one per cent gain, it’s a whopping 40 percent.

2. A desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world.

If you had to identify, in one word, the reason why the human race has not achieved, and never will achieve its full potential, that word would be meetings. Most modern management structures are historically, and somewhat inadvertently, designed to put up structural fences, which both stifle individual and team imagination and inhibit valuable serendipity. Both serendipity and imagination should be key to developing new ideas and driving innovation.

Locked within these established, widely accepted and frequently taught structures, managers and founders strive to know before doing and rarely do before knowing. As a result, their ability to take metaphorical Indiana Jones-style leaps of faith becomes tightly constrained as they strive to measure, test, and see what will support them across the conceptual abyss.

Before gathering a team together, engaging some advisors or facilitators and diving into another business strategy session in a soulless meeting room, founders and innovators should be concentrating on increasing pure creativity and idea generation. Perhaps only then will these meetings become truly useful tools to interrogate these ideas. Meetings could then become a sort of running through the mill process—where most new ideas could, and should, be rejected.

3. Brainstorming is dead.

The free association process embedded in brainstorming, and specifically its piggybacking approach, actively limits the participants’ use of imagination to develop new ideas. In 2010, Brian Mullen and his colleagues studied over 800 business teams and came to the quantitative conclusion that brainstorming groups were actually significantly less productive in both quality and quantity of original idea generation. In fact, individuals were more likely to generate original ideas when actively not interacting with each other.

In a survey with founders and co-founders of equity-backed, fast-growing, scale-up companies, over 75 percent of the respondents reported that they had their best idea “not at work.” When asked where they were when they had their best idea, 95 percent said “when I’m outdoors.”

In a hundred years or more, we’ll look back at the working practices of this past century and judge them, relatively, in the same way we now view Victorian mills and their cramped, squalid working conditions. We’ve asked people to spend the majority of their entire working lives, sitting in one position—confined to an often-uncomfortable chair, hunched over a small desk, peering into a small screen.

If you want creative workers, give them enough time to play. Entrepreneurs who engage their forward-looking imaginations, which materialize in their everyday performances, generate novelty and make a difference in the world.

4. Walking outdoors is a proven way to generate new ideas.

You’ve got to “walk the talk” before you can inspire others through your actions, both metaphorically and literally. Frederic Nietzsche famously said, “Sit as little as possible. Give no credence to any thought that was not born outdoors while moving about freely.”

Walking and talking is so simple and yet it’s one of those exercises that participants say has the biggest impact on their understanding of their situation and their relationships with others. Walking offers people an opportunity to connect on a human level, as equals, and share their perspectives. This experience can produce profound changes.

Getting ourselves into the important “soft fascination mode” through doses of immersion in the outdoors is sort of like an extended meditation retreat—except talking is allowed and there are no gurus. It causes your brain to ride alpha waves, the same waves that increase during meditation or when you lapse into a flow state. They can reset our thinking, boost creativity, tame burnout, and just make us feel better.

Walking, rather than just being outdoors, is the driver of novel, high-quality thinking. While research indicates that being outdoors has many cognitive benefits, walking has a very specific benefit—the improvement of creativity.

There is a specific type of “walking-for-thinking” that is separate from other types of walking. This walking has an optimal speed that synchronises rhythms of the body with thinking and vice versa. There’s a reason for this: while you’re happily concentrating on being vigorous, the brain slows to an alpha state, where your subconscious filters disparate thoughts and resolves the unresolved. This is a mental state where you’re more likely to get to the heart of things. New ideas synthesize, insights pop up, concepts tend to resonate and grow.

The removal of the boundaries, physical, mental and metaphorical, that we experience outside, directly translate and influence this thinking. The outside is full of metaphor for our thoughts—spoken, unspoken, cheesy, and transcendental. We have different conversations when outside, side-by-side, the narrative changes and stories materialize: this is called Outside Thinking.

5. Make it a habit through the 20:3:3 rule.

The trick now is to make this a habit, not a “nice to do” or an “I do it when I can” type of thing. Not something to be rescheduled because “something important has come up” or because of the weather. It is important in its own right and needs to be built into our own habits, our teams’ agendas, and our venture’s DNA.

Building on previous work by Michael Easter and pulling in all of the research for this book, the 20:3:3 rule should be followed: 20 minutes walking every day, a three-hour long walk every two weeks, and a three-day outdoors trip every quarter.

Simply put, the more time you spend outdoors, exercising your outside thinking, the more ideas you’ll have.

To listen to the audio version read by author Garry Pratt, download the Next Big Idea App today: