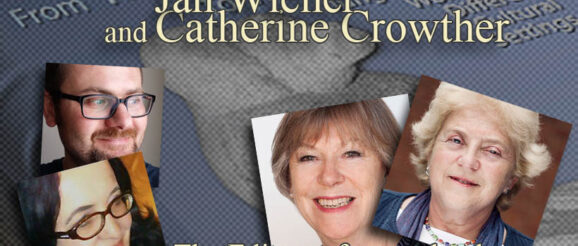

The Interview with Jan Wiener and Catherine Crowther – the Editors of “From Tradition to Innovation”e-jungian.com | Jungian online magazine – news, books, blogs, conferences and more…

The Interview was conducted online on 7th of August, 2015

Biographical information and book launch date can be found at the end of the interview.

LISTEN TO THE INTERVIEW:

MK: Malgorzata Kalinowska (also mentioned in the interview as Gosia)

TJ: Tomek Jasinski

MK: Our guests today are Jan Wiener and Catherine Crowther. We are meeting to talk about the special book edited by you: From Tradition to Innovation: Jungian Analysts Working in Different Cultural Settings which introduces into Jungian world a multicultural discussion about the training, its dynamic and principles. The discussion is multicultural, as it presents experiences of the teachers and the trainees working in different cultural contexts. The book is published when also in the psychoanalytic world different discussions are taking place about the training, and its dynamic. So this is very much a top topic today.

MK: Our guests today are Jan Wiener and Catherine Crowther. We are meeting to talk about the special book edited by you: From Tradition to Innovation: Jungian Analysts Working in Different Cultural Settings which introduces into Jungian world a multicultural discussion about the training, its dynamic and principles. The discussion is multicultural, as it presents experiences of the teachers and the trainees working in different cultural contexts. The book is published when also in the psychoanalytic world different discussions are taking place about the training, and its dynamic. So this is very much a top topic today.

Actually we first wanted to ask you how did it happened that you came up with the idea of the book?

JW: Well, first of all, Nancy Cater from Spring approached us, and I think through Murray Stein. Because what she wanted to do first of all, was a book about Russia. And she wanted a broad book about Russia, which might include some of the work that we had done over a long period of time about training. But she also is very interested in Russian culture. So I think she was interested in a book that might encompass not just developing groups and training, but also intellectual history, social history, music, art and so on. So that’s when we started to think about it. And then I think we felt that we would prefer to do a book that, again, was more focused on the overview or the review of the developing groups programs.

CC: We thought we would do a better book. Ourselves we would edit a better book about the things we knew.

JW: Yes.

CC: And it had really taken our interest.

JW: Yes. And one that had representation from all over the world, although actually it is missing South America unfortunately. But otherwise it has representation from all over the world, which would have also then enable to look at the dual relationship of the teachers and the people who trained, but in these rather different cultural contexts.

CC: I think that it grew out of the international conferences, that we were meeting people who were very keen to tell their story about what it is like to be trained and also quite a lot of colleagues who were very, very interested in working in other cultures. So, I think that in that point of view you are certainly right that it is obvious time. It came out of something which was really vibrant and active.

MK: Two aspects interested me very much. One is that in the book we’ve got the teachers speaking and past trainees speaking as well so there are two points of view presented. And also in the reviews you’ve sent us there is an aspect of the new emergent training emphasized, but on the other hand it is mentioned that this emerging form of training is important for the countries with established tradition of Jungian analysis. That these emergent trainings have a meaning for the established traditional trainings as well.

JW: Absolutely. Yes, and I think what we were interested in was that often it is theory that influences practice. But these projects, often they are pioneering projects certainly, when we don’t know the outcome. And we have to learn along the way. And we were a real example, when Catherine and I talked about it, of practice influencing theory. So it was the other way around. I think some of the experiences we’ve had from our established societies in teaching in other cultures were that we came home with revelations, we would have this big encounter with difference, that we could learn. Although we might have to write another book about the change in theory. We haven’t got enough into that. But you know, that was what was exciting. Some of the concepts that we were used to that were embedded in us from our training in a Western British culture. You know, how it changes when you look at them, whether in a Polish culture or in a Chinese culture, in a Russian culture and so on.

CC: I think it was things like what it means to be individuated and separate, and this sort of emphasis on different sorts of family structure and boundaries. All sorts of things which we just took for granted and we had to reexamine and think about. It was very, very stimulating and interesting. And the self. I think Jan has always emphasized how the self is a concept which really does have to be fluid. It has to be able to encompass all sorts of different cultural circumstances.

MK: It is extremely interesting, because the self is actually the central concept of here.

JW: Yes. And the other ones like – I was thinking in Russia for instance, whereas it may be true for you as well. You know, well, in England we are brought up in terms of oedipal issues and the Oedipus complex for example. For example the notion of children not being exposed in a traumatic way to the parents in bed together – the internal couple. When you go to Russia, which has a history of three generations sharing two rooms, it makes you have to rethink infant development and its effect, for example to ask the question is the Oedipus complex an archetypal event or not or how is it culturally influenced? It’s those things that have been so interesting and very challenging, I think.

MK: So, would that be redefining the relationship between individual and the collective as well, in a way?

JW, CC: Yes.

JW: And it really highlights the influence of the cultural level of the psyche as well as the personal and the collective. You know, that elevates itself through this kind of work.

MK: When we were thinking with Tomek about that, we were very much struck by the fact that it means very much coming back to the roots. When Jungian analysis started and when people were traveling from the different parts of the world to Zurich to train. The trainees at the Jung Institute were from different cultural contexts, and then they were coming back to their countries. So this multicultural element was present before different Institutes were established, very vibrant and alive. And then we are again in this moment when there are multicultural meetings but in the opposite way, because people are traveling to those countries.

JW: Yes.

MK: The trainers are traveling to those places and have possibility to experience the culture within the culture. And I think it is very special.

CC: Yes. It makes a huge difference to be living there for a few days. It teaches you to be much more observant and open.

JW: Yes. And also I think this was a source of conflict within the IAAP a while ago, when of course the trainings in Switzerland were feeling very threatened by these kinds of projects. But certainly, the more places I visited, the more important it feels to me that the work is done in the culture. Because, the main reason is that in the end people are going to have to work in groups. You know, you have to work together. Ultimately, if you form a Society, you’ve got to be able to manage the group dynamics and all the difficulties of the group dynamics, whereas when people individually go abroad to train, then you don’t have the emergence of the group culture, I mean that’s what convinces me that the work needs to be done in the culture itself, in the country or in the city.

CC:Yes. You don’t want to have an individual expert coming back from Zurich.

JW: Yes.

CC: You want people to learn together.

JW: Yes. I mean, Tomek came back from San Francisco, I’m being reminded of that. And you’ve integrated. I think you are one of the few, other people who had done the San Francisco training had found it very difficult when they came back to their country I think.

MK: I think that this integration is quite a difficult process.

TJ: Yes.

MK: It is a kind of crisis in itself; it needs to be a crisis in itself.

CC: But also there is that form of the established institutes arriving as experts. I don’t think that’s going to work either, to lay down the law. That’s really what the book is about. That there is no law that we can state.

MK: Yes. You know, in the last two months I’ve been two times in Ukraine and one in Czech Republic with the seminar about cultural trauma. It could be easier for me to hold this difference, because these are also a Slavic cultures. And although we share with those countries different troublesome historical processes, we are within the same collective psyche shape I would say. Myself, I also experienced those differences you are mentioning and how difficult it is to be embedded in the culture and make it from within, because it does something to your boundaries. It challenges you in a different way and I thought then how it could be difficult. But also, you know, I was just thinking about how it is a critical moment for Jungian analysis when there are so many new cultural influences influencing what is established and maybe this explains the kind of reaction that you Jan mentioned when analysts from Zurich were kind of thinking about it as of some troublesome moment.

JW: Yes. I think that we’ve worked through that now a lot. I think it’s not a majority. But yes, I think it is a key moment. And in a way the book, the chapters in the book, reflect on these processes in a mixed way. I think there are positive things – and nobody would not have done it – but there are also negative things or things that have been difficult. But I think it is hopeful. Well, Tom Kelly actually read the whole book and he’s done one of the reviews, you’ve read it. He has written something. But it was really important that he read it, you know [laughter], so that the IAAP, if you like, the generals that make the decisions are aware of what’s going on, as we say in English, at the coalface. You know, the foot soldiers that work on the ground. I think this book might, with its different views, be a chance to review some of the things or change things.

CC: Your chapter was very helpfully critical. I mean, it had lots of analysis of what the applications were of some of the structures. It is very useful.

JW: Yes. And there is another quite, not exactly critical but very thought provoking, two half-chapters on shuttle analysis. Two London analysts who have done a lot of shuttle analysis, some with interpreters in the room, and really reflecting both on the positive but also on the negatives of that.

MK: Yes. You know, our chapter was the result of actually a very long process of digesting our experiences, training experiences. And this was very important thing for us to be able to write it. It kind of marks the next step actually in thinking about it.

CC JW: Yes.

MK: And I was thinking… just coming back to what you said before, it was very important for me that Tom Kelly in his summary writes that the book is not getting into over-idealizing but at the same time it provides the well-deserved criticism. So it is kind of both.

CC: Yes. There is an interesting chapter from John Beebe, which is very different, because it is about the exchange of ideas. He was born in China. And he talks about Jung being very influenced by some Chinese philosophical ideas. And then he goes back to China on three or four occasions with lectures and he tracks in his lectures about trying to convey something of what Jung learned from China back to the Chinese. It is a wonderful circular chapter. That is not so much about training, it is more about ideas and influences across the world.

JW: And there is a chapter in it about one of our members Alessandra Cavalli who is a child and adult analyst has done a project in Mexico. It’s not a developing group but it’s a very different chapter about working with street children. And it presents a very interesting model of work, of working and supervising people who work with Mexican street children. And that again it’s just a very different approach.

CC: It uses the analytic attitude and ideas to do a very different sort of work.

MK: Martin Schmidt writes in his comment to the book something like this: “we see how orthodoxies are challenged and how Jungian analysis, like all things, is required to evolve to survive”. And I was just struck with this words “evolve to survive”.

JW: Yes. I think that may be a British point of view. Because you know in most analytic societies, not just the Jungian ones at the moment, the kind of analysis we do, especially more intensive analysis, is really countercultural, whereas in other places, like certainly Russia, I think in Poland too it is also at its beginnings. And then it’s enviable, because here [in the UK] with all the pressures for targets, American systems being imported, short term treatments…

CC: Value for money…

JW: Value for money… what we do and what we trained to do…

CC: We have to fight much more.

JW: And we do have to chane… the SAP is having to change and adapt to the culture which most of us are very happy to do but there are always a few, in our society anyway, they just want to do everything the same as it has always been done. A bit like in Switzerland maybe.

CC: That’s why we titled that book “From tradition to innovation”.

JW: Yes.

CC: We honor the traditions, but you have to be able to move into adaptation, without selling short your original values and what you understand and know from the traditions.

MK: I am thinking now about the global communication that is taking place nowadays, that one cannot avoid being influenced by it, it just happens. It is similar to what you said about the American standards, about the market etc. influencing the type of therapy that is being done. And then it kind of challenges the very essence of Jungian psychology.

CC: Yes, it does.

JW: The benefits though are this: I mean the benefits of technology of course, that’s such an important area which we could have had a chapter in there about that too. There will be in Trieste a whole session on technology now, because that’s one of the benefits of new things – for example that we now can have this kind of conversation. There can be Skype supervision and Skype analysis, which is not perfect but it’s good enough. So there are benefits too of new systems and changes… Sorry, what I was going to say was the other thing that Catherine and I did was a weekend teaching in Serbia for people in developing groups from Slovenia, Serbia, and Bulgaria, Hungary, Lithuania, there wasn’t anyone from Poland. That, they loved.

CC: They were mostly routers, not all.

JW: Because then they begin to see what’s going on in their communities and they can talk about their different training programs in an overlapping way. And that sort of partnership and joint teaching, they really liked it you know, and that’s a really good thing across boundaries and so on. I mean, you can’t do that in Russia probably or in China but in Europe you can do it, because the distances to travel are much shorter.

MK: Yes. Tomek, you wanted to say something…

TJ: Well, I was just thinking that this is an innovation itself. Those circumstances, as Jan said, that we can talk on Skype and have Skype analysis and Skype supervision…I’m thinking about how it touches on something fundamental. I think me and Gosia we talked about it a bit – how it has to do maybe with an issue of the relationship between psychoanalysis and culture in general. I mean, it is not just about the Individual Route but it is about the relationship between psychoanalysis and culture in general. Something about what Catherine said I think: how do you find yourself in a certain historical moment, the cultural moment, and not losing sight of the basic values of the meaning of what the analysis is, of what this particular way of understanding psyche and understanding the world is. Because I think this is what is challenging. What’s coming up out of it for me, what is the point of tension, so to speak.

MK: So how does the identity change in a way.

TJ: Yes. It is a matter of identity.

JW: Yes.

CC: I agree. And also I think that we’ve had to learn a lot about history: our history and other countries’ history and how they meet. And actually one of the chapters by Stefan Adler is very much about that. He is German and has been teaching in Russia and Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

MK: What was very striking for me when I was in Ukraine and Czech Republic with that seminar about trauma touches the issue of historical identity. We Polish tend to look at ourselves how much we need to improve and how much we need to get better, and we are all the time complaining about our different faults, and it is our national tradition I would say. And In a way I think we do not see the things that we do well, that we achieve. I was challenged in a way when I heard there the opinions that we Polish do embrace more bravely the cultural trauma aspect and that we are able to talk about it more openly, as this is not so obvious in other cultures. It was just a shock for me, because I thought that this is obvious that I have to learn a lot and that others are better. And then when you see yourself in the eyes of the others you are challenged with your identity and this meeting changes it.

CC: Yes.

MK: So then the things aren’t taken for granted. I have been also very much interested in some concept lately which is called multidirectional memory, it’s in a book by Michael Rothberg, in which he emphasizes how we can perceive our own traumatic cultural aspects through the eyes of other countries’ histories. And I was wondering whether your own cultural context kind of changed when you were working all those different points of views.

CC: I think, I hope it’s altered. I feel as if it always is.

MK: Because you said something, for example, about boundaries, that this was a change…

CC: Yes.

JW: We write about that quite a lot, you know, how we had to keep the idea that the work that we do always is boundaried and to think carefully about what we do, but the boundaries have had to be a bit more elastic than they are here. And a lot of what we both teach is all being about boundaries. I mean, I think that’s the main thing I make.

CC: The frame in which analysis takes place.

JW: Yes. And that’s what people have to think about most. Certainly in Russia when we did that. And Catherine did a very good paper in Serbia about boundaries and frame and they really liked that.

CC: And, it wasn’t… I mean, because it makes people think – that you have to invent your own internal boundaries, you have to understand why there are rules, you know, what a frame really means. And it was different for each culture. It was very enjoyable for us, very stimulating actually.

JW: And particularly it changes, because we are also visitors in other countries and therefore we get insecure, you know, in a certain way. It’s not like people all coming here where there is a way of doing things. And I think of how this made me more flexible in a certain kind of way in my work in London. You know, it certainly changed my practice in terms of… being willing to be lost more [laughter]. You know, because when you go to some of those countries, in the beginning you are just completely lost. In Russia, certainly in the beginning. And I think there is something about that which is not being omnipotent about what we know but being able to have an experience of being lost and then finding something together with, whether it is a supervisee or a patient or something like that.

CC: Yes. You see you make a mistake and you sort of fall into some trap you haven’t realized was there and then you have to really find out about it.

MK: It is quite interesting what you’ve just said because it seems kind of true meeting with the East, how it formulates. One of our writers in Poland, Andrzej Stasiuk, wrote a book “The East” about his experience of the East and going farther on the East into territories of Russia and further. And he writes that this is the territory in which the human means less and the space means more. That the human gets lost in space, in some kind of way. So the more we move to the East the less the human means in relationship to space, his embedded in it.

JW, CC: Yes.

MK: For me having analysis in Great Britain and going there for several years every month, it was like moving myself to the kind of edge, you know.

JW, CC: Yes.

MK: It is a state when you don’t really belong to your culture and do not belong to that you arrive at but at the same time you belong to both, and then a kind of borderland space emerges about which we write. If this borderland space is not created, tensions are – I think – very big.

JW: Yes. And I think there is a book to be written about language and interpretation. I was talking to a colleague, he is called Ali Zarbafi and he is a member of the SAP. He is Anglo-Iranian and he does a lot of work across cultures. He will be in Trieste, he will do the social dreaming, and you should talk to him. I was thinking just this morning that you know that’s a whole other area about what it means for you. You work in a language that isn’t your first language, and the role of language, all of that. There is a chapter in the book about interpreting but I think that it’s another whole area in this field.

MK: Yes.

CC: Yes, the mother tongue. Working in a mother tongue or working through an interpreter. I have loved working with interpreters, because the sort of quality of the language comes across, the different constructions and the way that ideas are conveyed in a different way. I really liked that.

MK: Do you know that in Poland we say “Father Language”?

JW: Father Land, father language.

TJ: Father Land, yes.

CC: We say “Mother Tongue”, it is interesting.

TJ: But that is… I’m thinking about what Catherine just said, that’s this thing about the borderland, that I think we are also writing in our article, that it is so challenging but in the same time it is so tremendously creative, can be so tremendously creative.

CC: Absolutely.

TJ: I mean, just by bringing all those little peculiar, potentially difficult and yet creative situations. All those, you know, mistakes, misunderstandings, yes.

CC: That’s right.

MK: There is left one last question: we were thinking whether it could be said that this book (and this form of training – routers training) was not only the result of the new political and social changes in a world but it was also a kind of response to something that happens in the Jungian world, as you said…

CC: When you wrote that in your email I really liked it. I think you should have written this chapter actually [laughing]. It was a very good thought that maybe it is part of the renaissance that we are just part of it, yes.

JW: Yes. I agree with that. And it didn’t happen… it emerged anyway. The whole thing emerged, I think.

CC: It wasn’t an idea that we started with. An idea came as we went along.

JW: Yes.

MK: So the book will be published the next month…

JW: Well it is in print and it will be launched. We will have 60 copies in Trieste. They didn’t want to send any copies and we said: no, there are lots of people in these countries that don’t have credit cards and they won’t pay with Euros, you know. So there will be 60 copies and we are going to have a launch party, to which everyone is invited. We’ll have a glass of wine and just celebrate it. And you won’t be there Tomek, sadly.

TJ: I wish I could be there, really. But it just feels like it is going to be a tremendously important event. When I think about the conversation today it seems like the more I think about it the more the book really seems to be…still more important on yet another level. Not just in terms of the theory of training but the theory of analytical psychology in general and even more.

JW: Well, we’ll see. Somebody will have to write some reviews of it.

TJ: [laughing] Yes.

CC: Everybody we asked to write was very, very enthusiastic. They really wanted to write about their experience.

MK: So we will be keeping up to date at our website with the news about the book and we are happy to write about the reviews as they will appear. We think it is extremely important.

CC: Very good. Well thank you for your publicity. It is very nice.

MK: Thank you very much.

TJ: Thank you very much for making time.

JW: And Gosia we will see you in Trieste and see you…soon, Tomek.

TJ: Okay, thank you.

JW: Have a nice weekend, bye.

CC: Thank you and goodbye.

Catherine Crowther is a Training Analyst for the Society of Analytical Psychology (SAP) in private practice in London. She worked for many years as a psychiatric social worker, family therapist, and psychotherapist in adolescent and adult mental health services in the UKs National Health Service. She was past chair of the SAPs adult analytic Training Committee and is involved in supervision and teaching in the UK and in Eastern Europe. Together with Jan Wiener she was the organizer of the Russian Revival Project, 1996-2010, an IAAP programme for the clinical and academic training of Jungian analysts in Russia. She was also a teacher and supervisor of clinical work in St. Petersburg throughout that time. She has contributed articles and chapters on analytical psychology on subjects such as silence, fairy tales, moments of meeting, cross-cultural exchange, eating disorders, supervision, and training.

Catherine Crowther is a Training Analyst for the Society of Analytical Psychology (SAP) in private practice in London. She worked for many years as a psychiatric social worker, family therapist, and psychotherapist in adolescent and adult mental health services in the UKs National Health Service. She was past chair of the SAPs adult analytic Training Committee and is involved in supervision and teaching in the UK and in Eastern Europe. Together with Jan Wiener she was the organizer of the Russian Revival Project, 1996-2010, an IAAP programme for the clinical and academic training of Jungian analysts in Russia. She was also a teacher and supervisor of clinical work in St. Petersburg throughout that time. She has contributed articles and chapters on analytical psychology on subjects such as silence, fairy tales, moments of meeting, cross-cultural exchange, eating disorders, supervision, and training.

Jan Wiener is a Training Analyst and Supervisor for the Society of Analytical Psychology in London. She is currently Director of Training. She was Vice-President of the International Association for Analytical Psychology between 2010-2013 where she was also the Co-Chair of the Education Committee, with particular responsibility for Developing Groups of Analytical Psychology in Eastern Europe. Together with Catherine Crowther, she organised a programme of academic and clinical teaching in Russia and has been involved in teaching and supervising clinical work in St. Petersburg since 1996. She has taught internationally for many years, and is the author of chapters and papers on subjects such as transference, supervision, training, and ethics. She is also author of three books. The most recent, The Therapeutic Relationship: Transference, Countertransference and the Making of Meaning was published by Texas A&M University Press in 2009.

Jan Wiener is a Training Analyst and Supervisor for the Society of Analytical Psychology in London. She is currently Director of Training. She was Vice-President of the International Association for Analytical Psychology between 2010-2013 where she was also the Co-Chair of the Education Committee, with particular responsibility for Developing Groups of Analytical Psychology in Eastern Europe. Together with Catherine Crowther, she organised a programme of academic and clinical teaching in Russia and has been involved in teaching and supervising clinical work in St. Petersburg since 1996. She has taught internationally for many years, and is the author of chapters and papers on subjects such as transference, supervision, training, and ethics. She is also author of three books. The most recent, The Therapeutic Relationship: Transference, Countertransference and the Making of Meaning was published by Texas A&M University Press in 2009.