The Lost Art and Innovation of Milk Plastic

Got milk? Pour yourself a glass and gulp down some little-known history about the household staple. In the early decades of the 20th century, milk was commonly used to make many plastic ornaments, including jewellery, gemstones, buttons, decorative buckles, fountain pens, fancy comb and brush sets and even piano keys. Milk plastic was even used to adorn Chanel’s first “little black dress” and make jewellery for the English royalty. Now If you thought the only animal on the farm to ‘give’ us wool was the sheep, you’d be mistaken. The humble cow, the giver of milk, butter, cheese, beef, leather and more also gave us wool. And if that’s news to you, this ‘wool’, a plastic-like material derived from her milk, would be woven into haute couture designer dresses and crafted into all manner of fashion goodies. And when blended with cotton or silk, milk fibre makes an excellent home furnishing fabric, robust and luxurious. Holy cow indeed!

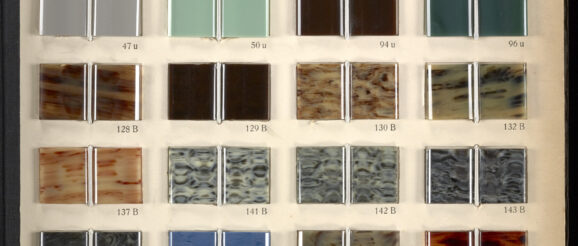

Created by German chemist Fredrich Spitteler in 1895, this horn-like plastic material was marketed as Galalith or ‘milk stone’ and first exhibited at the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1900. Galalith was in essence, a cheap sheet and tubular material derived from skimmed milk. As with many inventions, they often come about by sheer fluke, and the discovery of this hard sheet-material was in fact a failed attempt to find a white substitute for heavy dark slate schoolroom blackboards. This fabric couldn’t be moulded, but could be easily be pressed, cut, and machined into smaller objects and soon became a horn and ivory substitute for the blossoming global fashion industry. Versatile, multi-purposeful and biodegradable, Galalith could be created in any colour and the sheets marbled in all combinations of stained glass-like patterns. Milk extract is also referred to by its chemical protein name Casein and some of its properties had been exploited as a glue and colour pigment fixing agent as far back as the days of ancient Egypt.

The year 1909 would see our humble farmyard bovine engage with the radical Italian Futurist movement lead by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876 – 1944). The Italian Futurists wanted to start anew, turn away from the dogmas of the historical past and craved all things novel, from grammar to art and industrial production, but particularly the development of entirely new materials for a new age. The glorification of past military conquest, aristocratic riches and religious wealth would be replaced with the adoration of nature, its wonders – and its derivatives. And what could possibly be more revolutionary than to magic up plastics from milk?

Plastics, so commonplace for us today were at one time considered exotic. Indeed, Britain’s Queen Mary of Teck (wife of King-Emperor George V) ordered many pieces of jewellery at the British Industries Fair in 1915. Mary, one of the most famously bejewelled of all British monarchs, not only commissioned, but repurposed and adapted the old and the unfashionable throughout the inter-war years.

The first half of the 20th century saw the industrialisation of the dairy industry with mass markets demanding butter. As butter was churned from the thick fatty cream of cow’s milk, the remaining ‘skimmed’ or reduced fat residue after separation was dumped by the hundreds of thousands of litres as the regular milk market was already saturated. At the time Italy – like other European countries – had an excess of skimmed milk production from the dairy, butter and cream supply, and Galalith was the perfect way to soak up this unusable white ocean. Fifty kilogram of skimmed milk would produce 2 kg of valuable Galalith, with all its potential aesthetic and utilitarian applications. ‘Milk Fibre’ or ‘Milk Wool’ was a regenerated protein spun from the casein found in milk. In 1920, Marinetti’s Futurists published their Manifesto of Futurist Women’s Fashion showcasing an innovative new fabric: milk!

By 1926, in France, Coco Chanel’s now classic little black dresses appeared in Vogue, adorned with none other than Galalith costume jewellery. Ideal for easily working and colouring into the intricate Art Nouveau and Art Deco shapes of the day, this milk-bling was now accessible to women of all classes. Auguste Bonaz, a French merchant and Jakob Bengel, a German manufacturer, were the leading exponents of this new high fashion jewellery, supplying exquisitely crafted geometric chrome and coloured pieces for the 1920s and 30s Art Deco market. Whist the pre-20th century designs could be easily imitated or copied, the new protein plastic could produce intensely coloured plain or marbled flats and plates, ideal for cutting and grinding into decorative industrial parts – the new aesthetic of a brave new machine age.

In 1930s Italy, milk-fibre had its own splash as Mussolini was determined to rebuild Italy into a modern, leading, self-sufficient and industrialised nation. He advocated and invested heavily in the production of new materials, including milk fibre, as he sought to develop a quintessential ‘Italian style’ in furnishing, interior decoration and clothing that, up until that point, had not existed (even though Italy had an early start with artificial fibres with the development of viscose in the late 1920s). The SNIA Viscosa company was producing almost all of Italy’s 16% of global viscose output and in 1935, purchased the rights of the now perfected milk fibre, this time styled Lanital (a compounding of ‘lana’, meaning wool, and ‘ital’, from Italia). So successful was Italy’s innovative drive, the British Pathé News reels reported, ‘you’ll be able to choose between drinking a glass of milk and wearing one’. Milk fibre was – literally – flavour of the month.

Mussolini, bloody-minded and determined to have his new Rome, ramped up Lanital production. Meanwhile Marinetti became the marketing bard for SNIA Viscosa, penning The Poem of Torre Viscosa and The Simultaneous Poem of Italian Fashion – his odes to the glorious new products of the Italian textile industry. In his Poem of the Milk Dress, Marinetti extols the virtues of Lanital:

“And let this complicated milk be welcome power power power lets exalt this

MILK MADE OF REINFORCED STEEL

MILK OF WAR

Unsurprisingly Mussolini put his Italian fascists flags on the Lanital brand (of which one survivor from 1944 recently came to auction in 2018). These were his ‘Textiles of Independence’ and the Italians sold patents for Lanital production around the world. Marketed to the USA in 1941, the product was rebranded Aralac and by 1944 it was integral to the American fashion and garment industry. Aralac was incorporated into all aspects of clothing production, most notably military uniforms, even after the USA had entered World War II in 1942.

The technical problems with Lanital, however, were manifold: it was not as strong as wool, neither as elastic or thermally efficient. Unlike real wool Lanital didn’t suffer from attacks by moths, but it did stink when wet – a smell (unsurprisingly) not dissimilar to fermented or sour milk. The fermented milk aroma would ultimately be its downfall. Technology was ever-progressing and new, cheaper and better performing artificial or oil-based fibres such as acrylics were being developed and almost immediately took the place of milk fibres.

What would our world look like today if we’d followed the milky way? Although milk plastics have largely faded into obscurity with the advent of more advanced materials, Galalith is still in produced today, although in small quantities and almost solely for buttons. Casein glue is still also used to apply paper labels on glass bottles (it’s cheap and effective and easy to remove during recycling of the glass). The brief ‘golden age’ of milk plastics serves as a reminder of nature’s resources in our increasingly urgent need for sustainable alternatives to the fossil fuels used in so many of today’s plastics. There’s no arguing that transitioning back to milk plastics on a large scale would require overcoming untold logistical and economic, and political challenges. But the continued investment in milk plastics might have driven further research and development in the field of bio-based materials, potentially leading to the discovery of other sustainable alternatives to reshape our world in more environmentally friendly ways. Food for thought indeed.