The Real Security Innovation Gap

Editor’s Note: U.S. power has long rested on the brains of its scientists and engineers, who have churned out a range of innovations that have made the U.S. military the best in the world and offered ordinary Americans tremendous benefits as well. U.S. innovation, however, is faltering in key areas, leaving significant security vulnerabilities. Sarah Sewall and Michael Vickers, both former senior government officials now at In-Q-Tel, identify critical innovation gaps that threaten U.S. security and call for the United States to rethink its approach.

Daniel Byman

***

If the United States takes one lesson from the coronavirus crisis, perhaps it should be that U.S. security hinges on more than military capabilities. Washington would never accept a level of military readiness akin to our pandemic unpreparedness: The United States lacked reliable early warning; ongoing battle damage assessments; adequate equipment stockpiles; and effective operational tactics, techniques, and procedures—while pursuing unseemly beggar-thy-neighbor competition with our closest allies to import medical masks from Wuhan, of all places. But because a global pandemic lay outside the traditional defense paradigm, the U.S. government was underprepared. Unfortunately, viruses are not the only “outside the box” security vulnerabilities that demand government action.

Over the past few years, our work at a nonprofit, national security-focused technology investor has highlighted a growing gap between the innovation that the nation needs most and what the private sector is willing and able to fund. The greatest risks pertain to sustaining U.S. preeminence in key technologies—not supporting our defense capabilities per se. The U.S. government has become overly reliant on the private sector to deliver critical innovation without fully recognizing that a commercial bottom line might diverge from or underdeliver on the nation’s comprehensive security interests. Meanwhile, other nations have dramatically expanded research and development efforts, and China in particular recognizes technology as key to its national power.

One area of special concern is microelectronics. Chips function as the heart of everything from critical infrastructure to commercial innovation. U.S. firms remain strong in chip design and manufacturing tools, but Asian companies fabricate and package much of the world’s semiconductors. A growing interest in “reshoring” production facilities in the United States is necessary but not sufficient to meet the nation’s needs. Location alone won’t guarantee that U.S. startups can access production lines or that facilities will be state of the art. And while maintaining a secure semiconductor supply is important, so is pioneering the next generation of chips.

To fuel the nation’s economic strength and national security, American firms should be driving innovation in new packaging technologies and next-generation materials that can disrupt current industry practices. Unfortunately, private U.S. investors are not as interested in hardware—which requires large up-front investments and long-term capital—as they are in the software and tech-enabled consumer services that promise faster and often larger payback. The U.S. government will need to increase basic research funding, create applied research facilities in partnership with industry, and incentivize private investment to catalyze this effort. Without a push focused on disruptive innovation—not just relocating production—the United States risks falling behind in a vital industry that it created.

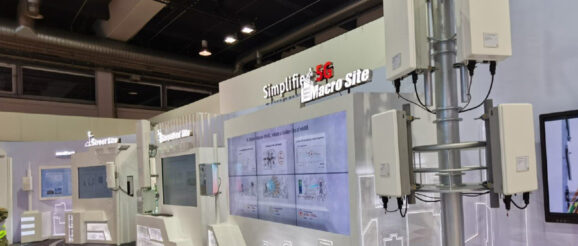

Today’s global telecommunications market represents another vulnerability. The dominant firms offer proprietary, comprehensive network solutions, and the United States isn’t even in this market because it doesn’t make a key component. But the real problem is China’s role. Chinese subsidies and support have helped make Huawei the dominant provider of 5G equipment internationally. This creates security risks because the Chinese government can compel Huawei’s cooperation in security matters, which could grant the government access to the information traveling on its networks and potentially provide China control of foreign infrastructure.

The best alternative is to accelerate what many observers refer to as “openness”—the standardization of interfaces to allow the interoperability of equipment components. This would upend suppliers’ current practice of offering a “take-it-or-leave-it” choice of a comprehensive proprietary system. With openness, telecom carriers could mix and match equipment components, which would allow customized networks that would reduce costs and improve performance. Critically, openness could also enhance security by making software more accessible, facilitating component replacement and enabling a diversity of suppliers.

The private sector is unlikely to drive the requisite innovation in time to address U.S. security concerns. In spite of some inspiring domestic startups, U.S. investment lags because market demand is uncertain. Government policies as well as investments would help overcome this inertia and disrupt the current global industry model. These could include financial incentives for RAN (radio access network) disaggregation, convening industry to shape mutually beneficial outcomes both for incumbents and startups and for equipment providers and carriers, and analyzing the relationship between U.S. spectrum allocation and global competitiveness. An open, commoditized 5G network is more consistent with our democratic and market-oriented values, and it could curtail Chinese control of global information networks. But it won’t happen fast enough without a push from U.S. policymakers.

Leading and shaping the evolution of biotechnology is perhaps the nation’s most consequential technology opportunity and risk. The stakes transcend the challenge of pandemic preparedness. Synthetic biology—using DNA sequences and genomics to engineer new biological parts, devices, and systems, or to redesign systems already found in nature—is poised to transform myriad aspects of our economy and lives. The nation best positioned to seize that opportunity will have critical economic, social and political advantages. Parts of the U.S. private sector are investing heavily in aspects of biotechnology. But the nation remains poorly positioned to transition our decades of investment in basic research into actual engineered products, and the U.S. DNA sequencing data library—foundational for synthetic data research—is a fraction the size of China’s. The United States risks becoming a laggard rather than a leader in the bio revolution. Failure to reverse these trends could prove catastrophic.

There are encouraging signs that government thinking in these domains is evolving. The Trump administration is funding vaccine development efforts and successfully lobbied the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company to build a new chip fabrication facility in the United States. Congress recently has drafted a flurry of legislation to boost government support for microelectronics, 5G, pandemic prevention and other technologies.

As the season of must-pass bills approaches, Congress should seize the opportunity to address commercial technology investment gaps. But since there are limits to what the U.S. government can spend, Congress also must be discerning. It shouldn’t fund industry to do what it already is planning to do, or mistake reshoring production for a comprehensive solution. Initiatives must spur real innovation and merit taxpayer support. This means looking beyond further shrinking today’s CMOS (complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor)-based chip design, toward new modes of packaging semiconductors together or creating next-generation materials for chips. It means supporting openness as a diplomatic and geostrategic objective, as well as a route to improve rural broadband access. It means recognizing that pandemic preparedness is just one aspect of biosecurity. Synthetic biology will literally transform our world, and it must be the United States, not a nation with starkly different values and interests, that midwives that process.

Effective action doesn’t require becoming like China, with its centralized control and fusion of civil-military sectors. The United States has its own approach to balancing defense and private-sector interests, protecting supply chains, preserving a “defense industrial base,” and creating strategic stockpiles. The coronavirus pandemic shows that the nation should make similar efforts to promote a broader set of national interests.