The Surprising Mix of Tradition and Innovation in Nepal’s Contemporary Art Scene

The Vietnamese monks said they wanted a river. So Lok Chitrakar, one of Nepal’s most prominent painters, wrote “need river” amid the folds of a landscape on a preparatory sketch for the gateways of a Buddhist monastery in Vietnam.

These drawings stretched across the wall of a room in Chitrakar’s studio when I visited Nepal late last year. I was there to see the reinstallation of a 10th-century sculpture of a deity into the shrine it had been stolen from in 1984. I had expected to spend most of my time thinking about the art of the past — but I couldn’t help being drawn into Nepal’s vibrant contemporary art scene. During my trip and in subsequent interviews, I asked some of its most notable participants to talk with me about mixing tradition and innovation and balancing the spiritual and commercial in their art practices — and I discovered that works by one of the country’s preeminent modern artists, Lain Singh Bangdel, is currently on display in Queens.

Chitrakar’s name is a clue to his profession. The Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley have a profession-based caste system, and the Chitrakars have long followed their name’s Sanskrit meaning: “image maker.” But Chitrakar’s father tried to persuade him to follow a different career path, believing that it had become impossible to make a living creating paubhā, the devotional paintings used in Newar Buddhism. (They are sometimes called thangka, the name of the related Tibetan style of Buddhist devotional paintings.) The practice declined during the 1960s and ’70s, when new students were scarce and many established practitioners turned to producing quick copies for the tourist market.

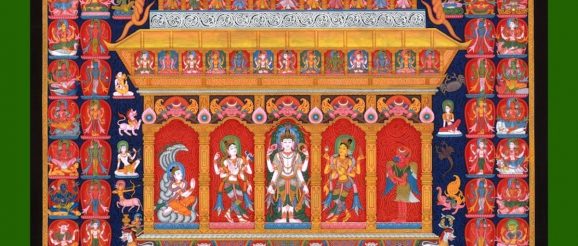

But Chitrakar, born in 1961, persevered. His paubhās, painted following the exacting dictates of traditional form and subject matter in hand-ground mineral pigments bound with buffalo-hide glue, are now in collections and Buddhist sites across the globe. Chitrakar also receives commissions, like the one from the Vietnamese monastery, for designs to be used by other Nepali metal- and woodworkers to produce three-dimensional works in traditional Newar style.

Since at least the 13th century, works by Newar artists have been highly valued by patrons from Tibet, India, and other Buddhist communities. Chitrakar correctly anticipated that the lull during his youth was temporary. Now, the streets around the major Buddhist pilgrimage sites in the Kathmandu Valley are lined with artists’ shops selling deities in paint, limestone, wood, and copper. Ordinary tourists take some home, but the most magnificent examples are commissioned by Tibetan Buddhists eager to establish new sanctuaries outside their homeland.

The Valley’s sought-after artists used the pandemic to catch up on these orders, often placed years ahead of time. Chitrakar also finished an enormous painting of the elephant-headed deity Ganesha, who is worshipped in both of Nepal’s major religions, Newar Buddhism and Hinduism. The artist had to climb a ladder to unveil the painting to me. Its intricate details took him 20 years to complete. Ganesha, worshipped as a remover of obstacles, is usually shown as a peaceful deity sampling a bowl of sweets. Chitrakar’s magnum opus depicts his wrathful side. Holding a skull cup and flourishing a variety of weapons, Ganesha dances, symbolizing the strength necessary to protect his devotees.

Chitrakar was easy to find, but it took me much longer to track down another artist I wanted to meet. Many neighborhoods in the Kathmandu Valley are adorned with murals, paste-ups, stencils, and other forms of street art. I especially admired a mural with saddhus — Hindu ascetic sages — meditating on heaps of coals, intertwined with bouncy figures wielding spray-paint cans, wittily squirting out the traditional scroll-shaped depictions of clouds.

I finally spoke to Sadhu X, who created the mural in collaboration with the illustrator Nica Harrison. Today, Sadhu X’s works blend traditional iconography and modern influences into his own distinct style. But when he was growing up, the only street art in Nepal was made by visiting foreign artists. In 2010, as he was completing his undergraduate degree, a teacher suggested he use the stencils he was creating on walls outside those of his art school. He followed the advice, soon met others interested in creating street art, and helped found the art space and community Kaalo.101.

Helena Aryal, who also joined the video call, is another of Kaalo.101’s founders. She expressed her frustration at the perception, both inside and outside Nepal, that street art is a Western phenomenon. Aryal insisted that although the medium might be foreign, the form is deeply rooted in Nepal’s history. The hand-painted paper illustrations of snakes (nagas), pasted on many homes and buildings in the Valley during the annual rainy season festival, confirm that paste-ups are nothing new in Nepal. And the concept of creating art by modifying the public landscape also fits in well with the interactive, multisensory nature of devotion in Nepal, where worshippers in open street-corner shrines leave fingerprint marks in vermillion powder on deities’ foreheads and offer them marigolds, perfumes, food, and even music, by ringing bells. Some shrines are covered in names written in marker — not casual graffiti, but reminders to the gods about who has prayed for what.

Sadhu X told me that he’s never seen a rigid distinction between the style of traditional paubhās and the work of street artists he admires from other parts of the world, who also use flat, graphic linearity to create exaggerated, instantly recognizable forms. Sometimes he thinks that his work is helping traditional Nepali art to evolve, but more often he’s just mixing together his influences and inspirations because he wants to tell stories using a visual language that he hopes his audience will understand. His work, and that of others associated with Kaalo.101, suggests that the distinctions between labels like ancient and modern, or foreign and Nepali, will blur if you shift your point of view.

The Kaalo.101 artists aren’t the first to question what should endure about traditional Nepali style. I also had long discussions about this question with Birat Raj Bajracharya, a scholar of Newar Buddhism and part owner of a gallery selling the works of artists intent on both preserving and transforming paubhā painting.

The gallery was founded by Bajracharya’s father. Like Chitrakar, Bajracharya’s father wanted to be a paubhā artist, but, unlike Chitrakar, he could not find a teacher. Instead, he studied art in Italy for years, returning in the 1990s with the goal of incorporating the emotional expressiveness and three-dimensionality he was impressed with in Catholic religious art into the Newar tradition.

To his father’s ambitions, Bajracharya has added the aim of recreating paubhās lost to theft. He collects photographs of paubhās in foreign collections, the most magnificent of which were likely stolen from Nepali monasteries, and encourages painters to make new versions. Bajracharya also reads ancient Newar religious texts (often after locating these, too, in foreign archives) to find descriptions of scenes from paintings that have vanished entirely.

Like Sadhu X, Bajracharya does not see a fundamental distinction between traditional Newar style and classical European models. For example, he pointed out to me that the texts describe paintings as portraying deities with emotionally expressive faces. But such expressions are difficult to render in the linear style of traditional paubhās. Bajracharya thus believes that the more complex shadings of emotion captured by artists who use European Renaissance techniques and the full range of colors of modern pigments may better approximate the ancient texts than the older paubhās.

But while Bajracharya agrees with Sadhu X that artists can remain true to their roots while departing radically from traditional style and medium, he’s far closer to Chitrakar when it comes to form. Bajracharya advises the artists associated with his gallery about details like the color, attributes, and hand positions of deities in their paintings, making sure they follow the standards passed down in Buddhist and Hindu texts. He wants art to transform without “letting go of its core sense”: its religious function. He wants all the paubhās sold by his gallery to be usable as meditational tools, even if purchased by a non-Buddhist collector.

Yet another mixture of traditional and modern is on view through April 9 at the Yeh Art Gallery at St. John’s University in Queens, which is hosting the first American exhibition of the paintings of Lain Singh Bangdel (1919-2002). Bangdel studied in London and Paris in the 1950s before coming home to Nepal, where he adapted the literary realism and abstraction he had studied to portray his home country in novels and paintings.

Although firmly a modernist, Bangdel was also an advocate for the preservation of Nepal’s cultural heritage. In 1989, he published the book Stolen Images of Nepal, whose photographs of sculptures in situ before their theft has provided evidence for many recent repatriation claims (including this one, for which Hyperallergic broke the story). One painting in the current exhibition, 1969’s “Bolt and Vortex,” reflects Bangdel’s intertwined interests. The curators interpret the bolt as a vajra, a weapon with the power of a thunderbolt frequently wielded in Nepali representations of both Hindu and Buddhist deities.

Back in December, after showing us his Ganesha, Lok Chitrakar invited us to have a cup of tea. One of my companions, the novelist M.T. Anderson, asked Chitrakar how he dealt with the problem of ego. His works help others pursue enlightenment through contemplation — but didn’t his renown increase the risk that pride or profit would further remove him from his own spiritual goal?

Chitrakar took a sip of tea and looked at his current project: another massive painting, this time of the Buddha refusing to let his meditation be disturbed by swarms of tiny figures symbolizing the “defilements”: hatred, delusion, and greed. He told Anderson he believed that the defilements are not entirely evil. For example, Chitrakar explained that he uses the sense of pride he takes in his work as motivation to drive him to create more, to help more viewers catch a glimpse of true peace.

Chitrakar’s reminder that nothing human is wholly good or evil applies to all the factors shaping the lives of Nepali contemporary artists. Tradition and innovation; global connections and local roots; meditation and marketing: all these can be tools for creating better lives and communities. The different solutions and goals of Chitrakar, Sadhu X, Bajracharya, and many others in Nepal show that there’s no one best path to the future of art.