The Surprisingly Long History of ‘Choose-Your-Own-Adventure’ Stories | Innovation| Smithsonian Magazine

The new Netflix original horror movie Choose or Die turns on an interactive computer game called “CURS>R,” which resembles a classic ’80s adventure program in which a user inputs text to move the story forward. Naturally, there’s a twist—the protagonist discovers that every choice in the game, no matter how small, will determine whether she and the people around her stay alive.

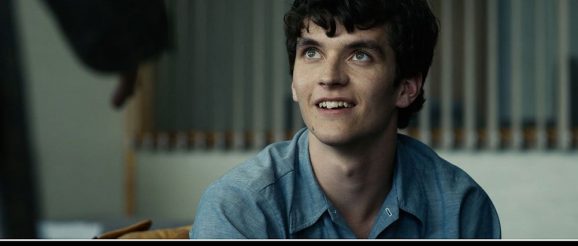

While the movie itself isn’t interactive (something that could have helped rehabilitate the plot), the release reflects Netflix’s growing interest in choose-your-own-adventure-style programming. Since the debut of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch back in 2018, the streaming service has been steadily investing in these titles. It’s easy to be a little cynical about this interactive programming push, which feels like a ploy for Netflix to find new relevance as a mobile gaming platform, especially now as it reports its first subscription losses in a decade. Nonetheless, I’m excited to see where it goes, because this format is ripe with the potential to break us out of linear narratives and democratize storytelling, giving each viewer the power to explore possible scenarios and decide what should happen next.

The concept behind interactive storytelling isn’t new. Arguably, it goes all the way back to the I Ching or Book of Changes, the ancient Chinese manual of divination and prophecy that employs cleromancy (the tossing of lots) to read its predictive text. Before the computer age, contemporary scholars Anthony J. Niesz and Norman N. Holland make the case for expanding the definition of the rudimentary interactive form to include “alternate endings to any narrative, either from authorial revision (as in Great Expectations [1861]) or deliberately (as in The Threepenny Opera [1928])”.

But it’s American authors Doris Webster and Mary Alden Hopkins who get credit for pioneering the concept as we know it today with the 1930 publication of Consider the Consequences! The romance novel, which included 43 alternative endings, empowers the reader to decide the fates of Helen Rogers and her suitors Jed Harringdale and Saunders Mead.

Scholar James Ryan, who shed light on this forgotten novel in 2017, pointed out that while the concept of the plot may seem obvious to us now, Webster and Hopkins’ interactive branching narrative was revolutionary at the time. “It’s a radical idea,” Ryan said in an interview with KZSC Santa Cruz, “that you can pack multiple plot paths into a book and let the reader decide which paths to take.”

Another foundational text during this era was Argentine writer and poet Jorge Luis Borges’ 1941 short story “El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan” (“The Garden of Forking Paths”). While the philosophical work is not interactive itself, the paths and directions of alternative realities it suggests became an important early offering to the field of interactive fiction—and is even considered the earliest precursor to hypertext, as defined by computer programmer Theodor Holm Nelson, who coined the term more than two decades later, in 1965, as a form of non-sequential writing—or “a series of text chunks connected by links which offer the reader different pathways.” (Of interesting historical note, Borges’ contemporary, American scientist and policymaker Vannevar Bush, also foreshadowed the concept of hypertext with his fictional “Memex” machine, which used “trails” to link books, records, and other forms of communications in a kind of nonlinear narrative.)

Advances in technology continued to push interactive fiction out of the theoretical and into the conceptual. Jumps in movie-making, for example, led to the debut of the first interactive film, the Kinoautomat, in 1967. Premiering at the Czechoslovak Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Montréal, the film (which was originally titled Člověk a jeho dům: One Man and his House) was shown in a custom-built theater with green and red buttons installed on every seat. During the screening, the action was paused every so often, so that a moderator could appear on stage and ask the audience to vote on questions that propelled the plot forward, such as:

Should Mr. Novak let a woman clad only in a towel into his apartment, just before his wife arrives home?

Should Mr. Novak rush into an apartment despite a tenant blocking his way?

Should Mr. Novak knock someone out to bring attention to a small fire?

However they answered the prompts, the movie always ended in the same way: a building in flames. Was the film a political statement against fixed elections? A satire of determinism? These questions swirled as it became a smash success of the World’s Fair, and awakened filmmakers to the possibilities of interactive cinema. According to director Radúz Činčera’s daughter Alena, after its debut “all the big Hollywood studios” wanted to license the Kinoautomat, but the Czech government, which owned the film, refused to sell.

If things had gone another way, the Kinoautomat might have become a household name, pushing Americans’ idea of what interactive technology was capable of. It joined the ranks of other experimental literature emerging at the time, such as Julio Cortázar’s 1963 book Rayuela (translated to English as Hopscotch in 1966), which let the reader “jump” through 155 chapters with the help of a “table of instructions,” and Robert Coover’s disquieting 1969 short story “The Babysitter,” where a night of babysitting could be as mundane as a quiet night watching TV or end in increasingly disturbing scenarios, like the babysitter being stalked, raped, and murdered.

Instead, most Americans’ first encounter with interactive fiction came thanks to the mass-market success of the Choose Your Own Adventure novels. Lawyer Edward Packard thought up the concept in 1969, as he was telling his daughters a bedtime tale about a man on a desert island. “I couldn’t think of what should happen next,” Packard later recalled to Marketplace, so he asked his kids what they would do. The girls provided two different answers, and Packard saw a genre with potential. “They could not just identify with the main character, but they could be the main character,” he said.

Packard struggled to sell the concept at first—“It was just too strange and too new,” he later said—but publisher and author R.A. Montgomery, having worked in role playing-game design himself, finally recognized its potential. In 1979, the Choose Your Own Adventure series officially launched with The Cave of Time, where you might encounter a T-Rex or a UFO, depending on which route you opted to hike.

The series attracted a wide readership; however, its formulaic style gave the genre a bad rap. As one English scholar put it bluntly, “in terms of literary quality, many of the multiple-storyline books are true skunks.” But it’s important to remember that the series was marketed toward children, who loved the straight-forward simplicity of the questions, like, “If you take the left branch, turn to page 20. If you take the right branch, turn to page 61. If you walk outside the cave, turn to page 21.”

Today, books, video and computer games, television and films continue to push the boundaries of what interactive fiction can do. The potential control readers can have over the story can, at times, feel downright radical (take author Stuart Moulthrop’s mind-bending hyperfiction text Victory Garden). But the decisions don’t have to be extreme to make an impact; there’s something to be said for the more quotidian of the choose-your-own plots that continue to crop up (for me, one of the most anticipated offering on the horizon right now is the first interactive rom-com). After all, whatever weight the decisions carry in these plots, the act of choice remains central to each of them, and helps to remind us that not only is there a multiverse of possibility out there, but that each of our decisions can create a ripple effect.

As Consider the Consequences! argued back in 1930, “life is not a continuous line from the cradle to the grave.” Rather, the novel explained in its introductory text, our journeys are made up of “many short lines, each ending in a choice, and a branching right and left” that lead us on to ever more choices.