This may be the most perfect carbon innovation yet | National Post

Article content

A decade ago, I was an elected politician and a member of Treasury Board when the Sturgeon project was under construction and in trouble — over budget, behind schedule and with engineering that didn’t quite work. Today, the project looks genius. I’m told the value of the carbon credits nearly pays for all the costs to operate the refinery. I also understand MacGregor’s a little bitter about how it all played out, for him personally, in the end. But he’s a guy who lives to dream up mega-projects and see them run, and so I reach out to him to find out more about H2Naturally.

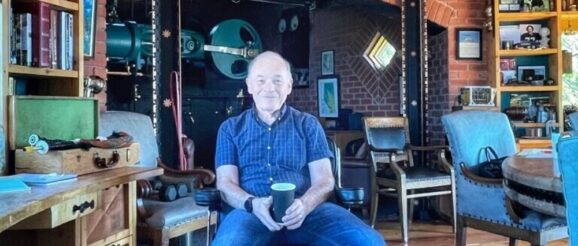

MacGregor has a private “Museum of Making,” a 20,000-square-foot underground collection of machinery and tools tucked into the foothills northwest of the town of Cochrane, Alta., and we agree to meet there.

As I turn onto the winding 1A highway, the former TransCanada, the peaks of the Rockies are obscured by forest fire haze. On my car radio, the newscaster describes how a climate protester splashed paint on a Tom Thomson painting hanging in the National Gallery of Canada.

On arrival, MacGregor’s grin lightens my mood. It’s his 74th birthday; he’s enjoying the day away from his downtown Calgary office. We sit at an enormous wagon-wheel table, coffees in hand; floor-to-ceiling windows overlook a pond and trees, with a Nietzsche quote etched into the wood trim: “In the mountains of truth you never climb in vain.” It’s hard to conjure up a more bucolic setting to talk about forests and the trees.

Article content

“You have to see the tree as a temporary storage device,” he begins. “It takes the carbon out of the atmosphere, then it falls down and rots and puts it back into the atmosphere. But you can accelerate that process, you can manipulate that.”

H2Naturally’s big idea involves partnering with First Nations communities living in forested areas and setting them up with machines to convert low value firewood into wood pellets, shipping those pellets to a state-of-the-art wood refinery to be built north of Edmonton, refining the pellets into pure hydrogen as cheaply as possible and selling that hydrogen as a molecule to other refineries, or chemical and fertilizer plants and capturing the carbon and selling carbon credits for lots of money.

Two decades ago, the problem to be fixed was figuring out how to cost-effectively capture carbon. There were naysayers, MacGregor recalls, people asking: are you sure you can do it, how expensive will it be, why are you doing it?

For MacGregor, mega-projects need to be evaluated through the lens of societal value: is it going to be a good thing over the life of the project? “If you look at the Chunnel, it probably cost three times what they estimated but could you do without the Chunnel today? Could you think of a world where you replace the Chunnel with airplanes?”

It’s also essential to build alignment with the people who own the resource, he reflects. When the Sturgeon refinery was built, the bitumen feedstock was owned by the people of Alberta; it made sense to partner with the government of Alberta. With this new idea, the resource owners are the First Nations living in the hinterland.

Fort Nelson First Nation seems interested — they want local jobs — and talks with other Indigenous communities across western Canada are being initiated. “We’re going to help them to own significant, probably controlling, equity interest in the pellet plant,” MacGregor shares, “We’re going to pay a price for pellets that makes that pellet plant financeable.”

There’s still a lot of negotiating to be concluded with the federal government on investment tax credits, he explains, and “we’ve been working hard to get an off-take for the CO2 benefits.” Locking in a 20- to 30-year secure revenue stream for the project — the carbon offsets — is key.