U of G Air Filter Innovation Has Widespread Use From Cannabis to Auto Industry

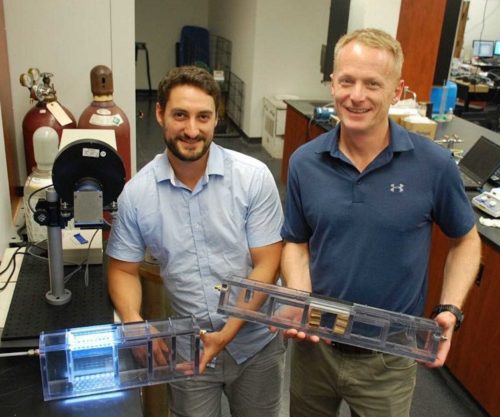

David Wood and Prof. Bill Van Heyst holding two SmogStop prototypes in the lab on campus

A benchtop setup in U of G’s “air lab” may hold the secret to cleaning up harmful highway smog and industrial pollutants, from automotive factories to cannabis producers – and even ridding homes of allergy-inducing or health-threatening airborne chemicals.

Turning results from a lab simulator into a novel air pollution control system for potential use in Canada and abroad is the goal of a University-industry innovation partnership eight years in the making.

The technology is still in prototyping stage, but early results from testing a Guelph company’s highway SmogStop barrier hold promise for the system’s ultimate use in a range of applications for cleaning indoor and outdoor air, says engineering professor Bill Van Heyst.

In 2011, his expertise in fluid mechanics drew the co-founders of EnvisionSQ, a local company that had contacted the University’s Research Innovation Office looking for potential collaborations.

The company was already working on pollution control technology using a photocatalyst, or a light-activated coating of chemicals that break down pollutants into harmless elements like nitrogen and oxygen.

EnvisionSQ aims to reduce the concentration of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as well as nitrogen oxides (NOx) produced in fossil fuel combustion. Through chemical reactions in the air, these pollutants form smog, reducing air quality and causing everything from asthma to cancer. Indoors, VOCs such as formaldehyde can enter the air from building materials, carpets and paints.

The company wanted Van Heyst to help improve an air flow system to work along with the photocatalyst in its highway sound barrier.

“They had a concept in mind and wanted proof that it worked,” he said.

His lab team tested early designs – including testing tabletop models and full-size barrier samples – in wind tunnels at other universities. They also developed LED arrays for activating the catalyst in their benchtop simulator.

Embedded in highway noise barriers, the passive system draws air through the smog-cleaning catalyst without the need for energy-draining fans or pumps.

In fall 2017, working with the Ontario Ministry of Transportation, the company installed several of its patented SmogStop barriers along a short stretch of Highway 401 in Toronto.

Each translucent acrylic barrier measures three metres long by 6 ½ metres high and functions as a conventional highway sound barrier. Inside is a channel that funnels and directs air past the photocatalyst.

Monitoring the barriers for eight months, the team found a 50-per-cent drop in NOx. The researchers estimate that, over a year, a kilometre of the barrier could remove 16 tonnes of NOx – the equivalent to taking 200,000 vehicles off that stretch of road every day.

Nighttime efficacy is lower, but the system still works with some types of highway lighting.

The company now plans to test a noise barrier in the United Kingdom. Engineering post-doc Dave Wood will visit the U.K. this summer to monitor that pilot installation. He began working with Van Heyst on the project for his post-doc in 2015.

The SmogStop project located near Bayview Avenue exit on Highway 401 (photo credit: Bill Van Heyst)

Ultimately, the technology might be installed anywhere, said Van Heyst: “Traffic pollution has been growing in every single city in the world.”

Now, the U of G researchers are helping the company explore other applications for its SmogStop air pollution control coating.

The technology may be used to reduce volatile organics from air inside or around factories. Scott Shayko, CEO of EnvisionSQ, said the company will install its system at an Ontario automaker. He’s negotiating to install the product as soon as this year at an industrial plant in China.

Referring to China, Shayko said, “They have a huge air quality problem. Their air pollution levels are often 10 times worse than here.”

Ideally, he said, the system would be an option in air-handling systems placed in condominiums or apartments.

Van Heyst said the technology might also help to control odours around a growing number of cannabis production facilities in Canada. The team has shown that the system destroys the terpenes that lend marijuana its characteristic “skunky” smell. Now, they hope to find a partner institution willing to test the system at a cannabis production plant.

Referring to the array of potential applications, Wood said, “The potential to have a global impact is really intriguing.”

Van Heyst said the project brings together cross-disciplinary aspects, including socio-economic, health and environment. As an example of industry-university collaboration and technology development, he said, “It allows us to bring a number of skills together to assist in solving a problem for a local company.”

He added: “I envision driving my grandchildren, and on the side of the highway would be a noise barrier, and I can say, ‘I helped do that.’”

Contact:

Prof. Bill Van Heyst

bvanheys@uoguelph.ca

David Wood

woodd@uoguelph.ca