Waite: 6 Education Innovation Trends You May Not Know About, From 173 Diverse Schools You May Never Have Heard Of | The 74

There’s no shortage of ideas about how nontraditional practices are taking off in K-12 schools, but often scant data to back them up — let alone data that can surface patterns and blind spots where we may not be paying attention.

The Canopy project, a collaborative initiative led by the Christensen Institute that reimagines where school innovation data come from and how they are analyzed, shows how building better collective knowledge enables a view into student-centered learning trends that may be difficult to detect.

The primary reason for this work is that while many schools around the country are innovating, even when data are shared, there’s no way for individual data sets to complement and build on one another to create a more comprehensive picture. As a result, knowledge about school innovation is fragmented and siloed, blocking the ability to surface trends and identify promising new practices taking off.

To begin the project this year, we invited a broad group of nominating organizations across different states to identify schools that are reimagining the learning experience for students; we then verified that information with schools. The resulting data include information from a diverse set of 173 schools across the country not commonly referenced on typical lists of innovative schools, which we’ve analyzed and shared in a new public report.

Here are a few insights from that research:

Big-picture trends

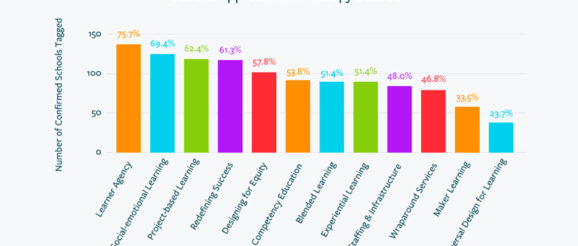

● Learner agency, social-emotional learning and project-based learning may be some of the most common innovative approaches in schools today. The Canopy project uses a set of 88 tags — keywords and phrases representing aspects of school design — to describe elements of the school’s design. Using these tags to sort, filter and analyze the data set made it clear which are the top 12 innovative approaches across the schools, with learner agency at the top of the pack.

● District schools — not just charter schools — are reimagining teaching and learning models. Charter schools receive much of the spotlight when it comes to education innovation and reform. But the district schools representing 67 percent of the data set are a good reminder that schools of many types are working toward student-centered learning, regardless of governance model or circumstance.

● Many innovative schools are operating under the radar. Knowledge about K-12 school innovation is often trapped in a word-of-mouth echo chamber, with colleagues repeatedly recommending to one another the same limited set of well-studied, well-known bright spots of school innovation. By pooling knowledge from a diverse set of nominators, we surfaced many schools that are working under the radar of the national conversation. After comparing the schools nominated in the Canopy process with 11 other lists and databases on school innovation, including Education Reimagined’s map, Getting Smart’s 2018 list of middle and high schools to visit and NGLC’s list of grantee schools, we found that 72 percent of Canopy schools were not named elsewhere, showing how crowdsourcing can help create a broader, more diversified picture of schools that are innovating.

Key geographic and demographic trends

● Rural schools may face barriers to innovation, or they are focusing their efforts more narrowly. Rural schools were less commonly tagged for all approaches, often significantly so. The exceptions to this were blended learning and wraparound services, where tagging rates for rural schools were closer to the rates for suburban and urban schools. This suggests that we should better understand how rural schools are trying to innovate, including targeted support for their efforts.

● Experiential learning and competency-based models appear to be less common in schools serving low-income students and students of color. These tags were more frequently indicated in suburban schools, those with lower rates of free and reduced-priced lunch and those with mostly white student populations. However, researchers and experts have argued that both experiential and competency-based models hold great potential for advancing equity. This brings important questions to mind about what barriers schools serving higher-poverty populations and students of color may face in implementing these models — or perhaps why they are opting to pursue different models to meet their students’ needs instead.

● Efforts to design for equity appear to be breaking down along racial and socioeconomic lines. Designing for equity is defined by putting the needs of historically marginalized students at the center. With that in mind, it’s encouraging that the designing for equity tag appeared in the vast majority of schools serving predominantly black students, as well as more often in higher-poverty schools. But designing for equity was dramatically less often tagged in predominantly white schools, and somewhat less often in lower-poverty schools. Given that virtually all schools serve some number of students whose experiences and identities (including and beyond race) are historically marginalized, this pattern raises questions about whether these schools are at risk of failing to meet the needs of marginalized students who may be in the minority.

Although the Canopy findings are not nationally representative, they offer a glimpse into important questions about how school innovation is evolving.

Chelsea Waite is a research fellow at the Christensen Institute focusing on blended and personalized learning in K-12 education, where she analyzes how innovation theory can inform the design of new instructional models.