Will coronavirus usher in a new era of vaccine innovation? | World Economic Forum

As this novel coronavirus continues to spread, and the number of people infected with COVID-19 keeps rising, the race is on to develop a vaccine. But the time it takes to carry out clinical trials, to ensure that a vaccine is both safe and effective, means this won’t happen overnight.

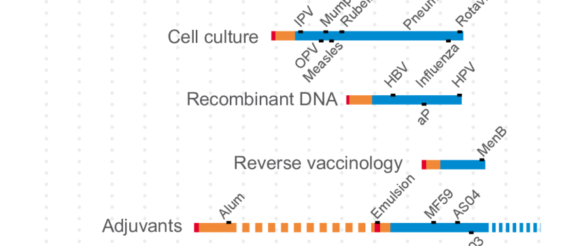

This has implications not just for the rapid availability of a COVID-19 vaccine for the current outbreak. The sheer variety of the novel types of vaccines being investigated and the approaches they use could serve us well for future outbreaks of other novel diseases. In the process we could finally see a range of highly innovative vaccine technologies take off that are radically different from traditional approaches, ushering in a new era in the way we fight infectious disease.

The advantage of using existing “platforms” like this is that the time it takes to carry out all the core research and clinical trials can be massively reduced because new vaccines can potentially be shown to be as safe and effective as existing similar vaccines instead of having to start from scratch.

In recent years, we have also seen the development of completely novel vaccine technologies that could dramatically speed up vaccine development, even against infectious diseases that humanity has never seen before.

Traditionally, most vaccines consist of a killed or attenuated form of the disease-causing virus or bacteria. When the vaccine has been administered, our body responds by producing antibodies against one or more antigens, such as proteins or carbohydrates, from that specific germ. This means that if we become infected in the future, our immune system is already primed to rapidly recognise and tackle the infection.

Newer DNA-based vaccines take a different approach. For coronavirus, rather than being made up of the coronavirus itself, they involve injecting a fragment of covid-19 DNA, containing instructions to build the antigens found on the surface of the coronavirus. Our cells use these instructions to assemble the antigens themselves. These are essentially just fragments of the virus which by themselves don’t pose the same threat as the virus. But our immune system still recognises them as foreign and produces antibodies capable of recognising the complete virus in future. Rather than waiting to obtain a sample of the virus and grow it in the lab before injecting killed or attenuated versions into the body, researchers are essentially outsourcing to our own cells the job of producing the antigens that teach our bodies how to recognise germs.

Other groups are developing mRNA vaccines that work in much the same way. Both methods have a number of potential advantages over traditional vaccines, but a significant one is the speed at which a candidate vaccine can be created. Finding a way to produce a suitable antigen on which to base a vaccine can take considerable time. But with DNA and mRNA vaccines you just need the genome. So in January when rapid genetic sequencing of the coronavirus was published by Chinese scientists it was possible to develop a vaccine within just days.

Another big advantage of approaches like these is their adaptability. They are sometimes called “plug-and-play” vaccines, as in theory DNA or RNA from a huge number of germs can be “plugged” into the same vaccine platform. When it comes to developing vaccines against novel infectious diseases, this really could be a gamechanger.

A variant on a more traditional protein-based vaccine approach, which involves injecting just proteins, effectively attached to nothing, directly into the body, is also being pursued for coronavirus vaccines.

Gavi is now looking at the potential role it can play when a vaccine or vaccines become available, to ensure that everyone who needs it has access to it, regardless of their wealth. With the current outbreak, the hope is that the outbreak will be brought to an end swiftly through non-pharmaceutical interventions.

The development of a vaccine offers an insurance policy in case this does not happen, but hopefully that insurance policy will not be required. However, even in that case, the work carried out on coronavirus vaccines today will almost certainly help us be better prepared for the next outbreak, whatever form that takes.