South-To-South Collaboration Spurs Innovation: Ugandan and Tanzanian Health Experts Join Forces – The Task Force for Global Health

Nabette’s work on this project is an example of what’s sometimes called “South-to-South,” a term describing collaborative or cooperative efforts between countries and institutions in the Global South. South-to-South collaborations are a critical method of advancing science and health in Africa. They help build local public health and scientific capacity, focus time and effort on local health priorities that are often neglected by the wider global health community, and can encourage deeper regional cooperation on public health.

Nabette says her experience and insights make collaboration with other African scientists different from collaborations with scientists from Europe or North America.

“When we’re working in Uganda or Tanzania, it’s easier to understand the context,” she says. “We’re working in similar communities with similar social, political and community challenges that, during a laboratory testing situation, would take time to explain to a colleague from the U.S.A.”

Along with having broader contextual commonalities, there’s also the common science. Working in a neighboring country can mean collaborating with scientists who have direct, relevant experiences with the same diseases you’re working on.

“When we field-tested the stool stomper, we noticed that the round pressor [the part of the device that presses stool samples between slides] made samples of uneven thickness,” explains Nabette. “We know from our work that samples have to be thin and even on the slides so that light can pass through them and we can examine them easily. We asked the stool stomper engineers to make the pressor rectangular. When they did, the samples became uniform and easier to examine.”

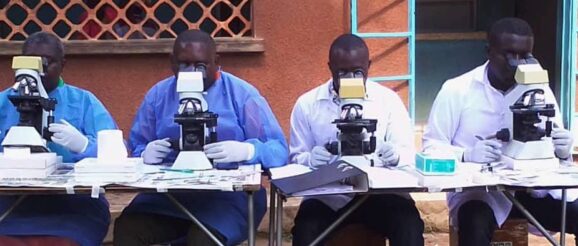

One of South-to-South’s most important attributes is that practical learning goes both ways. Nabette saw that her Tanzanian colleagues used image-taking microscopes she’d never used. When her group in Uganda gets similar equipment, she says, she’ll be able to train her colleagues to use them. She also says her professional network has meaningfully expanded.

“I can now text Dr. Honest Nagai [in Tanzania’s Ministry of Health and Social Welfare] in case I need advice on running a test or when I find a challenging situation in the field. He’s my backup plan now.”